Tenant Right of First Refusal

Read our latest on right of first refusal (TOPA).

A tenant's right of first refusal or "opportunity to purchase" would give renters first chance to purchase the property in which they reside, should it come up for sale. By giving renters the right of first refusal, owners necessarily have less freedom to dispose of their property as they see fit.

2023- 2024 Session (193rd)

We mostly stopped TOPA. A right of first refusal was granted to the state for properties previously subject to 'expiring use' tax credits for renting to Section 8. Most members were not affected.

2021 - 2022 Session (192nd)

- H.1426 An Act to guarantee a tenant’s first right of refusal, Jay Livingstone (D), Rob Consalvo (D) MassLandlords Opposes

- S.890 An Act to guarantee a tenant’s first right of refusal, Patricia Jehlen (D), MassLandlords Opposes

- They Want Your Property: Hearing Oct 12 on Right of First Refusal

What Tenant Right of First Refusal Advocates Say

Suppose an owner wants to sell their building. It could be because they are retiring and want to cash out. Or it could be that they can't operate or maintain the building and need someone more established to take it over. Whatever the reason, there is a good chance that the seller or the new owner will find it best to transact the building empty. Gut renovations, condo conversions, and renter screening can't take place with existing tenancies in place.

In the absence of a functioning housing market, the renters of this building, especially elderly and low-income families, stand a risk of being displaced far from that neighborhood or community the moment the building is put on the market. A right of first refusal as currently envisioned would ensure that either these renters or a non-profit of their choosing could become the owner of the property ahead of any private investor. Presumably then the current renters would continue to inhabit the premises at the current rents, avoid displacement, and have stability for life.

Advocates for a Massachusetts tenant opportunity to purchase or tenant right of first refusal most commonly say that rents are high and unaffordable. Some blame corporate and landlord greed for this. They say rents would remain low especially for low income and elderly households if only the renters themselves could own and maintain a building.

Right of first refusal supporters are nonprofits who don't want to compete on the open market the way this for-profit buyer has to farm for deals.

What we know about Tenant Right of First Refusal

Data on the effects of a tenant right of first refusal are available from Washington, DC, which passed the 7,000 word Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) circa 1990.

Tenant Right of First Refusal effect on Displacement

In late 2017, the I-Team investigated whether renters were staying in the apartments for which they had an opportunity to purchase right of first refusal. They reported that renters sold their right to the owner and then moved out.

The DC Association of Realtors claims not to have seen a single renter group buy their multifamily building in the thirty years the act has been law.

One attorney, Andrew McGuire, has based his entire practice around TOPA-chasing, and getting renters to accept cash to assign their rights to the owner to move out. He estimates the market is $100 million annually.

The act does not define what constitutes a renter, therefore is open to abuse by non-renters. Live-in nurses, roommates, and many others have legal authority to claim the right of first refusal. They are then free to take the money and leave. (Note that this would be similar in Massachusetts: live-in nurses, roommates and other renter guests can easily obtain full rights as tenants, even if only having just moved in without the landlord's permission.)

Since renters invariably choose to accept displacement in exchange for the cash payout, Washington DC has begun the process of repealing TOPA as a failed policy.

Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act Cost to Owners

Colin Johnson of the DC Realtors Association told the I-Team investigating TOPA that he had seen payouts to renters as large as $50,000 to $100,000 for single family homes, which were in higher demand than multifamily housing.

Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Economics: Elderly and Low-income Renters

Maintaining a building requires 24/7 responsiveness, difficult work, and access to capital. Elderly renters and low-income renters, even when banded together, often do not have the resources to maintain an aged building. We discuss this issue at length in our article, Tenant Right of First Refusal: An Essay on the Merits and Shortcomings as Public Policy. This is why typical right of first refusal legislation allows the right to be assigned to a nonprofit.

Tenant Right of First Refusal Talking Points

As a public policy, we believe the tenant right of first refusal or opportunity to purchase has several flaws:

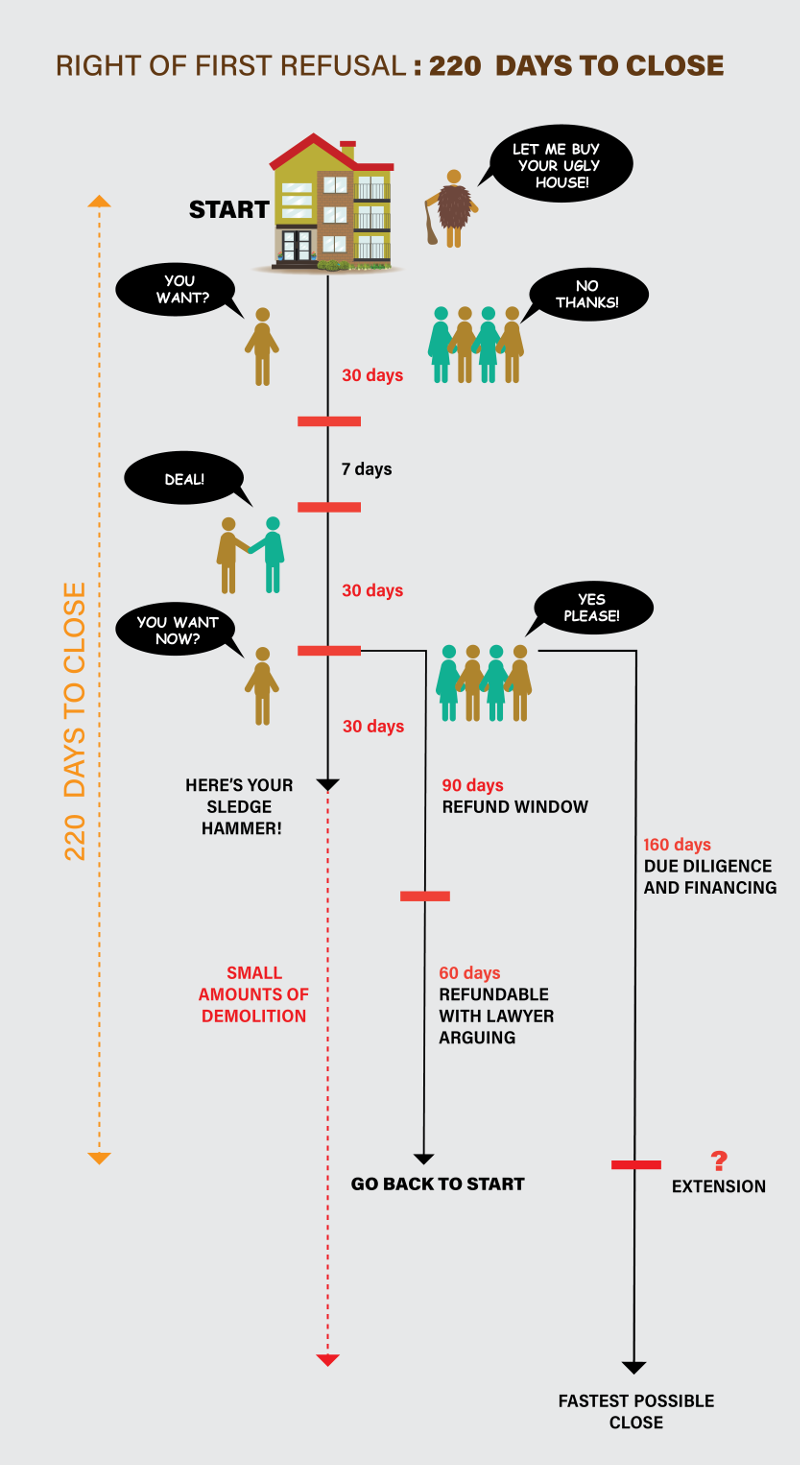

- It delays the sale of multifamilies and further hampers the rental housing market

- It fails to prevent displacement

- It is a form of legalized extortion

- It reduces the tax base

Flaw 1: Tenant Right of First Refusal Hampers the already Constrained Market

The Right of First Refusal being discussed in Massachusetts provides up to six months for renters to get financing to purchase after a private landlord has made an offer. During this time, nothing can happen to the building. The proposal recognizes the difficulty of renters forming a tenant's union and getting financing. They fail to recognize the fact that investors and would-be landlords simply won't shop for multifamilies in communities with a right of first refusal. No one is willing to conduct all the due diligence required, make an offer, and then wait six months to see whether the renters best it.

According to the 2016 Senate Special Commission on Housing, we need hundreds of thousands of new homes to restore our housing market to efficiency and accessibility. A right of first refusal as currently envisioned will drive the market in exactly the opposite direction, preventing the infusion of new capital into our housing stock.

Flaw 2: Tenant Right of First Refusal Fails to Prevent Displacement

As we have seen in the Washington, DC Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, renters can sell their right to anyone and reap a windfall reward. Some Massachusetts versions of the proposal eliminates the windfall payout but fail to constrain the successor owner to keeping the renters in place. A nonprofit or a renters union that purchases a property is under no obligation to continue renting to the renters who originally assigned their right to the successor.

Nonprofits routinely have to make difficult funding decisions to fulfill their mission. If push comes to shove, they will readily evict a renter for nonpayment, clear out housing to make needed structural repairs, or terminate a tenancy to enforce federal law and avoid jeopardizing their federal funding (think marijuana usage permissible under MA state law but illegal federally). There is nothing in the proposal that actually grants protection from displacement, it's only possible that it might work out that way.

Flaw 3: Tenant Right of First Refusal is Extortion

The definition of ownership is the right to use and dispose of property as one sees fit. It's often the case that an owner will transfer title in order to facilitate their own business or family goals. For instance, an owner may move the property from being owned personally to being owned by a newly created wholly owned LLC. Under right of first refusal, owners have no choice in whom they will sell to. Owners cannot sell their property into an LLC they own, cannot sell to their irrevocable trust, and cannot sell or will to their children unless they first secure the right of first refusal to themselves. Title cannot be transferred with certainty unless the right has first been secured.

In the Washington DC scenario, securing the right of first refusal means purchasing the right for up to $100,000 per renter or whatever the going rate may be at that time. In the Massachusetts proposal, securing the right would mean creating a nonprofit and inducing the renters to assign their right to the nonprofit, an added cost.

The data from Washington DC show clearly that few renters remain in their homes after sale, with most electing to receive cash in exchange for signing their right back to the owner. By threatening to prevent a desired transfer of title until payment has been rendered, right of first refusal falls under federal definitions of extortion.

This YouTube short available 2023 May 11 from @greatmastermind shows how Derik Fay used right of first refusal in Florida to extort $20,000 per unit from an owner. Fay had paid renters $1,000 per unit for their rights.

Flaw 4: Right of First Refusal Reduces the Tax Base

Right of first refusal legislation typically allows renters to assign their right to a nonprofit, and bars them from assigning that right to a for-profit. The intent is to effect a transfer from for-profit owners to nonprofit ownership models. Although renters might not care about the tax treatment of their building's owner, municipalities should.

Each fiscal year, a municipality determines a levy, or an amount of tax revenue to be collected, most of which will come from real estate taxes. The rate assessed to single families can be different from the rate at which multifamily, commercial, and industry land is taxed. Often, single families pay less as a percentage of assessed value. The sum of "rate times assessment" across every property must add up to the required levy.

Nonprofit owners are exempt from real estate tax. They may be asked to make payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT), but such payment cannot be compelled. In September 2019, the Boston Globe reported that nonprofits in Boston pay only 23% of requested PILOTs. In other words, the same land owned by a nonprofit will produce one-quarter the normal tax.

To the extent right of first refusal redirects title to nonprofits, it reduces the tax base and increases the tax owed by others (e.g., single families) for any given municipal levy.

2019 - 2020 Session (191st General Court)

- Right of First Refusal Vetoed January 14, 2021.

- Consolidated Amendment A to H.4879 H.4887 An Act enabling partnerships for growth MassLandlords opposes.

- H.1256 An Act to guarantee tenant’s right to purchase Nicholas A. Boldyga. MassLandlords supports as an alternative.

- H.1303 An Act relative to guaranteeing the tenant's right to purchase David Henry Argosky LeBoeuf. MassLandlords supports as an alternative.

- H.1260: An Act to guarantee a tenant’s first right of refusal, Rep. Cullinane (D), MassLandlords opposes

- H.1315 (formerly HD 3740) Right of first refusal, Denise Provost (D), MassLandlords opposes

- S.786 An Act to guarantee a tenant’s first right of refusal Brendan P. Crighton. MassLandlords opposes.

- S.801 An Act relative to tenants’ opportunity to purchase Patricia D. Jehlen. MassLandlords opposes.

2017 - 2018 Session (190th)

Somerville Right of First Refusal

Related Pages

- Tenant Right of First Refusal: Details of MA Proposal, Comparison with DC TOPA (April 17, 2018)

- Tenant Right of First Refusal: An Essay on the Merits and Shortcomings as Public Policy (April 14, 2018)

- Tenant Right of First Refusal: Legislative Activity as of March 2018 (April 10, 2018)

- Open Letter to Massachusetts Legislators: Refuse Right of First Refusal (November 2018)