Would Boston Mayor Wu’s Rent Control Proposal Help or Hinder Housing?

| . Posted in News - 3 Comments

The article on this page refers to past rent control. Two years ago, we fought and helped derail Boston Mayor Wu’s rent control proposal, and we are determined to quell the current initiative, too. We are doing all we can to avoid a return to the disastrous rent control policies of the 1970s-90s.

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu’s rent control plan, which was recently published upon submission to the Boston City Council, contains few surprises and retraces policies from the past. Before it was published, some details of Mayor Wu’s plan were “leaked” and reported by numerous media outlets. We look at some of the plan’s details below.

Boston City Hall, at 1 City Hall Square, home to the office of Boston Mayor Michelle Wu. Image: CC BY-SA Daderot, Wikimedia Commons.

The proposal, which emerged from her mysteriously appointed Rent Stabilization Advisory Committee, attempts some distinctions from failed Boston and Cambridge rent control policies of the 1970s and 1980s. Those distinctions would not likely deter the ultimate failure of this plan, either.

Mayor Wu, who assumed office in November 2021, campaigned on a promise to tackle Boston’s housing crisis. Her pledge partly entailed policies that would aim to incentivize more housing development, but also included a return to rent control, which she calls “rent stabilization,” as a way to help renters. (A considerable amount of data from studies since the state banned rent control in 1994 refutes that premise. The majority of statistics on rent control show that such policies, contrary to helping, hinder low- and middle-income renters’ ability to find affordable housing.)

The mayor has quickly acted on her campaign promise. She formed a Rent Stabilization Advisory Committee last year to study the possibilities and connotations of rent control in Boston. We remain uncertain of how the committee membership was decided, and it has no representation from small-business housing providers. (At the time of writing, litigation had been drafted and presented to the MassLandlords board for a vote on whether to sue for public information disclosure regarding RSAC membership.)

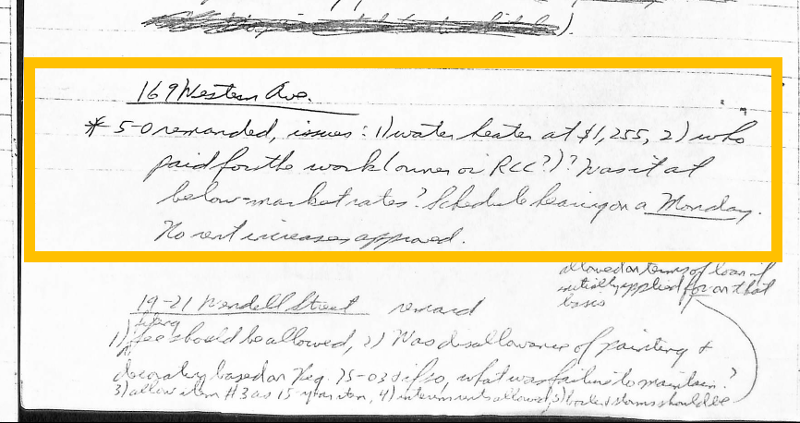

These scanned minutes from a Cambridge rent control board meeting Feb. 23, 1993 show a rent increase for 169 Western Ave on the basis of a $1,255 water heater installed. The request was denied.

Rent Restrictions and Fair Return

Most prominently, Mayor Wu’s plan would install a cap on rent increases throughout her Boston jurisdiction. Applying such a cap renders rental properties under rent-control regulated businesses, similar to utilities, and the issue of “fair rate of return” on investment enters the equation.

On paper, landlords would be allowed to raise rents no more than 6% above the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is used to measure inflation, year to year, with a hard cap of 10%.

However, a property with excess profitability could be denied rent increases entirely under the so-called “fair return” standard being proposed. There is no detail in the proposal for what a fair return might be or who should decide.

Massachusetts’ past rent control is littered with examples of landlords being denied rent increases by rent control boards.

Cambridge, for example, excluded mortgage payments from operating expenses and lumped legal fees into a set management allowance. Under this “fair return” standard, it was impossible for landlords to get rent increases for interest rate changes or evictions.

Quality Decline

Without a fair rate of return on investment, housing quality inevitably declines. Without revenue, rental property owners would have no means with which to maintain and upgrade their rental units.

It’s widely agreed that rental housing under rent control suffers from long-term deterioration, as one study (among several) notes about New York City. Upkeep and renovation costs money. Without it, as when property owners’ income is artificially restricted to very little or no return on investment, improvements and even regular maintenance slow down or cease.

It’s also not hard to correlate a precipitous drop in housing investment as a result of such a rent-control policy.

Already, new housing construction in Greater Boston is seeing a decline, with further drops anticipated. Cities and towns in and around Boston permitted 12% fewer housing units from 2021 (a year of high permitting), the largest decline in the city since the Great Recession. Some of that reduction can be blamed on higher costs, but anticipation of changes in Boston’s rental housing policy have also made a negative impact. An investor would obviously prefer to invest in housing in communities or projects, such as condominiums, that wouldn’t restrict ROI – potentially into negative territory – through policy.

Some Boston triple-deckers and multifamilies would not be subject to rent increase restrictions in Mayor Wu’s rent control proposal, which would exempt owner-occupied rentals containing six or fewer units. Image: CC BY-SA 2.5 Piotrus, Wikimedia Commons.

Rent Control Exemptions

Mayor Wu’s proposal seeks to alleviate housing production concerns. It would exempt new buildings for the first 15 years after being constructed, including housing built in the past 15 years. (We previously erred in reporting that this exemption was omitted. A bullet point at the bottom of page one had been dropped from the scanned version we had been given.)

The proposal would also exempt owner-occupied rental buildings with six or fewer units, as well as the following: temporary rentals such as hotels; dwelling units in nonprofits like hospitals and elderly housing; dormitories; public housing; and rentals that accommodate tenants on voucher programs.

The plan would also not apply between tenants. When a lease ends and a tenant moves out, an increase in rent on the lease for a new tenant would be unrestricted.

Alongside rent increase restrictions, the mayor’s proposal would also enact a “just cause” eviction mandate. This would allegedly disallow evictions without good reason, such as nonpayment of rent or illegal activity on the rental property. This is a hand-in-hand provision necessary to enforce rent increase restrictions. Without “just cause,” rent-controlled landlords wanting to raise rent in excess of the capped percentage could simply evict a tenant at any time for no cause and raise the rent as desired for a new tenant, rather than waiting for a lease term to end.

Even in cases in which clear lease violations are happening, many landlords are not able to prove such breaches in court and repossess their property. Consider a tenant smoking in a rental with a no smoking lease provision. Without evidence of smoking, which may be hard to obtain, a landlord in court is working against the odds.

A Return to Rent Control Boards?

Finally, in an unfortunate echo of rent control policies from the 1970s and 1980s, Mayor Wu’s plan would provide for the city to establish an “administrator or board” to oversee rent control regulations. Similar boards supervising past rent control rules became controversial because they were, at best, a substantial administrative expense, and at worst, vulnerable to corruption.

Mayor Wu’s plan would also allow for the city to regulate, by ordinance, condominium conversions and rental unit demolitions requiring move-outs. It would set citywide rules for tenant notification, relocation plans and payments to tenants, along with permitting guidelines and exemptions.

MassLandlords has scanned 2.7 gigabytes of minutes from rent control boards during the rent control years of the 1970s and ‘80s. We intend to create a website to publish our findings to demonstrate the vagaries of bureaucracy at work.

Rent Control in Other States

Mayor Wu states in her petition that her rent control proposal is modeled on rent control policies recently enacted in Oregon and California. In 2019, Oregon became the first state to implement statewide rent control. California followed in 2020, with a few differences from the Oregon law. Oregon’s policy restricts rent hikes to 7% above CPI in a given year. California’s law sets the cap at 5% over CPI, with carve-outs for municipalities that have rent control already in place.

Unlike Mayor Wu’s proposal with its 10% hard cap, neither California nor Oregon place maximum caps on rent increases. In 2022, the Oregon rent increase limit was 9.9%, but in 2023 (based on 2022 inflation percentage), it is set at 14.6%. It’s notable that Mayor Wu specifies that “advertised rents” in Boston increased by 14% in 2022 – less than Oregon’s increase allowed under rent control in 2023 – as a way to justify the need for rent control.

Several other states and cities are also considering or in the process of enacting rent control policies. One widely publicized example is St. Paul, Minn. The mid-size city abutting Minneapolis passed one of the nation’s strictest rent control laws in 2021 following ballot approval by voters. Under the law, St. Paul housing providers are allowed to increase rents no more than 3% in a 12-month period. Changes were made to the policy after its initial enactment when city legislators noted major decreases in new housing developments, and large-impact cancellations of some new affordable housing projects.

Even some of the 31 states that have banned rent control like Massachusetts are contending with communities lobbying to override state law and restrict rent increases. Cities in Florida and Nevada have introduced rent control policies. State legislatures in Illinois, Washington, Colorado, Connecticut and Rhode Island have seen various proposals recently. So far, no further rent control legislation has passed, but the issue is likely to hold interest as long as the nation’s housing shortage and resultant high market prices continue.

Rent Control Makes No Economic Sense

It’s been long established that rent control doesn’t work. Mayor Wu and others repeat that rent control is needed to help low- and middle-income citizens to secure housing that they can afford. Yet, multiple studies have concluded that wherever rent control has been implemented, affordable housing stock decreases and average rent prices increase. Rent-controlled properties end up occupied disproportionately by people who can well afford them, not by those they were intended to help.

One way to possibly avoid some of rent control’s most serious flaws would be to means test rent control for income. In theory, means testing would exclude renters with income over a set threshold from benefiting from rent-controlled rates. Without means testing in the past, rent-controlled units were too often monopolized by high-income renters, such as the mayor of Cambridge, for one example. However, a means-testing formula would be complicated. It wouldn’t apply to renters who receive vouchers, such as Section 8 program participants, because their full rent is guaranteed. To be effective, means testing would have to narrowly target a band of low-income renters who earn above the voucher threshold. But means testing at any level is conspicuously absent from Mayor Wu’s proposal.

It’s no surprise that a large majority of economists agree that rent control is not effective policy. It doesn’t make economic sense. High rents and home prices are economic indicators that demand is high while supply is relatively low. Otherwise, high rents wouldn’t be sustainable. Renters searching for homes would simply pass up high-priced units for better deals.

Not coincidentally, two of the cities in the U.S. with the highest rents, New York City and San Francisco, have both had rent control policies in place for many years.

Restricting the amount that housing providers can raise their rents does nothing to increase supply. In fact, it has an overall negative impact on supply for several reasons. It discourages renters from moving out of rent-controlled units. It also discourages new permits for rentals, encourages conversions to condos and other uses, and encourages long-term vacancy and “mothballing” for extended periods (such as, until after rent control is rescinded again because it’s proven to be so disastrous for housing).

Meanwhile, amid the resultant reduction in supply, demand for rentals remains constant, so that landlords of non-controlled units are able to hike their rents even more than they would in a normal, unrestricted market.

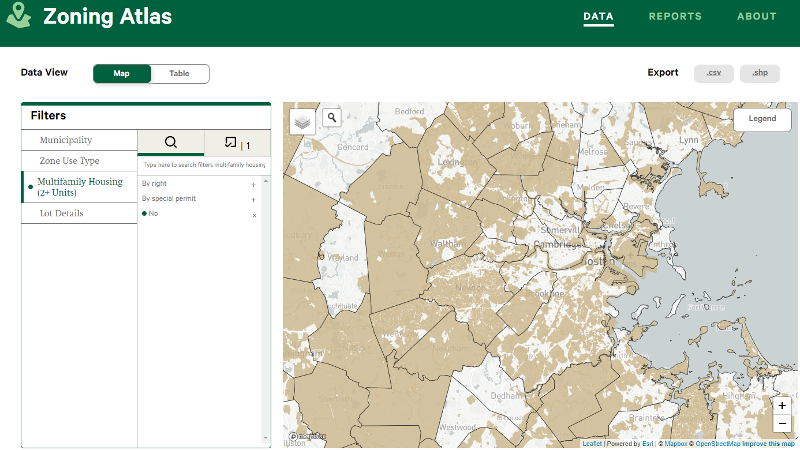

The MAPC Zoning Atlas shows in brown regions where multifamily housing is not allowed. Half of Boston is zoned effectively single family through parking requirements, floor-area ratios and setbacks. Public Domain Metropolitan Area Planning Council

Better Solutions Than Rent Control

Rent control unnecessarily creates a circumstance in which people holding rental units when rent-control policies take effect are the winners. Everyone else loses: rental owners, who lose funding for upkeep and improvements; renters seeking affordable housing, because fewer affordable units are available over the long run; and the city, which forfeits potential housing development as investors turn to other, unrestricted communities and more profitable projects.

But what if there were solutions that didn’t create winners and losers? As it happens, there are such options. And many of them are right in plain sight.

Rental assistance is one option. In the immediate term, while awaiting recent policies that encourage more housing development, increased rental assistance provided by the state (with some federal government funds) and city programs can help thousands of renters remain in their dwellings. Such programs are already in place, such as RAFT (Rental Assistance for Families in Transition) and HCVP (Housing Choice Voucher Program).

Of course, the efficacy of these programs depends on their successful administration. Unfortunately, in Massachusetts, tens of thousands of applications for rental assistance have been mishandled or “timed out” since the pandemic for unexplained reasons, resulting in untold numbers of evictions that might have been avoided. MassLandlords is amid a lawsuit against the Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) seeking information about these mismanaged rental assistance applications, to shed light on what exactly happened and why.

In the long term, zoning changes will help boost housing stock. Policies have already been enacted that allow municipalities to change local zoning ordinances by a simple majority vote. Such changes could open the door for multifamily housing, accessory dwelling units, open-space residential development and other projects that could boost affordable housing stock.

More zoning changes are needed. Many wealthy communities – especially Boston and its surrounding municipalities – maintain restrictive single-family zoning, with prohibitive setback, parking and lot size requirements. Such policies deter affordable housing development. Half of Boston is effectively zoned for single-family only, a condition that significantly restricts the city’s ability to expand its housing base. Shifting residential zoning in the city to multifamily by right would open thousands of opportunities for new housing construction. So far, multifamily by right zoning is not on Mayor Wu’s menu of housing proposals.

Rent Control That Could Work

Finally, rent control is an option, one that MassLandlords and housing providers could support – as long as property owners are compensated by the municipal or state government for the difference between market price and their restricted rent price.

MassLandlords recently submitted a letter to the Boston City Council pointing out that rent control is currently legally allowed under the above condition, as a provision of M.G.L. Chapter 40P, the state law prohibiting rent control. The 1994 ballot initiative banning rent control included an exception that remains in place: Section 4 of Chapter 40P allows towns and cities to enact rent control under certain conditions, one being that the local government must reimburse rental property owners for the market loss they incur as a result of rent control.

Rent Control a Counterproductive Outlier

Mayor Wu’s rent control proposal still has a way to travel before it would become law. Even if approved by the Boston City Council – not a certainty – it would need the signature of Governor Maura Healey. Healey has left the door open on such legislation, stating that “it’s up to local communities to make those decisions.”

Both Wu and Healey have introduced or passed legislation aimed at alleviating Boston’s and the state’s housing crises. Massachusetts ranks seventh in the nation among states with the highest rents, according to U.S. News, with a one-bedroom apartment renting for an average of $1,409. That statewide average is pulled northward by Boston’s high rental prices. The state’s largest city now ranks second in the nation for high rents, trailing only New York City, according to a national rent study by Zumper. That analysis finds an average two-bedroom apartment in Boston rents for $3,430.

Governor Healey has taken the steps of appointing a housing office and cabinet-level secretary to focus specifically on housing solutions. Longtime Salem mayor Kim Driscoll was appointed to that secretariat.

For her part, Mayor Wu has proposed plans addressing housing as part of her legislative agenda for 2023-24. One of her proposals is a levy of 2% on real estate transactions over $2 million, aimed at helping to provide funding for affordable housing and increase tax credits for low-income senior homeowners.

Unfortunately, the 2% levy and its impact on ROI would likely deter investments in rental housing. Alternatively, MassLandlords recommends a 2% tax on single-family dwellings as a way to encourage multifamily zoning and disincentivize residential zoning that swallows up land and stifles housing expansion.

Wu also proposes changes to the city’s Inclusionary Development Policy (IDP) that would lower the threshold requirement for affordable housing in new developments from 10 units to seven, and would increase the required percentage of income-restricted rental units in such developments from 13% to 20%. Again, such a change may further dampen enthusiasm among housing investors and developers as they steer clear of projects and places with policies that eat away at their investment returns.

Boston is an attractive place to live, work and learn. But the city – and the entire state – desperately needs more housing, especially affordable, multifamily housing. Policies that discourage investment and corrode business income only serve to reduce the supply of new, affordable and rental housing against demand.

Rent control is the foremost example of such a discouraging policy.