The Ashley Story: A Real-Life Example of Security Deposits Gone Wrong

| . Posted in advice, Did you know?, News - 2 Comments

A Massachusetts landlord thought he’d get $3,463 from his tenants’ security deposit. He ended up settling, paying them $6,000.

Introduction

This is a tale of two landlords. The first landlord, a small property owner whom we’ll call Mike, was considering investing in Massachusetts real estate. He knew the area and had friends and family here. Mike learned about the Massachusetts security deposit law, and about our other laws. It seemed to Mike that Massachusetts law exposed him to litigation and penalties. Ohio, another state where he had friends and family, didn’t seem so bad. Mike stored away his Massachusetts knowledge and invested in Ohio instead.

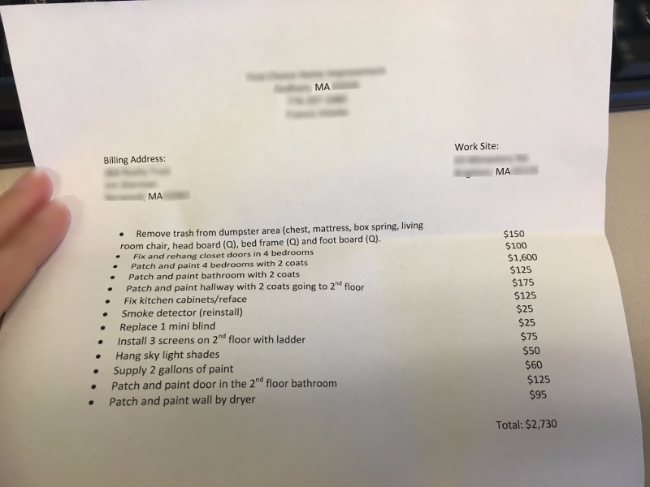

The underlying contractor charges were not permissible deductions because the landlord had not hired a licensed Home Improvement Contractor, and also, much of the cost was for items that should have been considered "reasonable wear and tear."

The second landlord, a larger owner whom we’ll call Larry, had built his business in Massachusetts just because he lived here. Larry had grown to a reasonable size, and by operating in the rising metro Boston market had been lucky with large appreciation and large rent increases over the years. He had operated successfully for a long time. He had common sense but no particular understanding of the law.

Enter Ashley, Mike’s friend and Larry’s former tenant. Larry said that he was withholding from Ashley’s security deposit, and furthermore, that Ashley owed him money. She asked Mike to see what could be done. Mike quickly unraveled Larry’s entire case.

No Deposit will be Returned, see Bill Enclosed

Ashley’s two-year tenancy was typical. Four non-family renters shared a single unit. The conditions statement was signed at the start of “year one” by all four tenants. The security deposit amount was $2,975.

Between years one and two, Ashley and another tenant remained in the unit, but the two old roommates left. Two new roommates moved in with the landlord’s permission. A new lease was signed.

One time, the water bill was very high for some reason. There was also a winter where snow wasn’t cleared properly and each party blamed the other. Larry had charged Ashley for the water and the snow, and Ashley had paid.

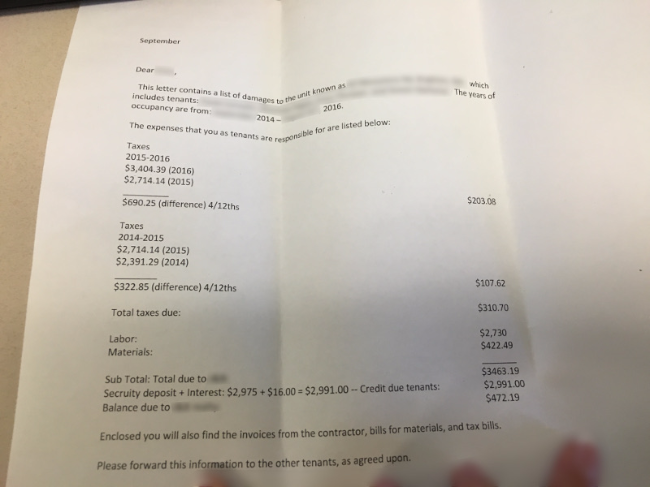

At the end of the tenancy, Larry presented Ashley with a good faith effort to comply with the security deposit law. Larry sent a letter clearly stating the tenants’ names, the premises, and the original amount of the deposit.

Property taxes had gone up, so he had deducted the increase from the deposit in accordance with the tax escalation clause in the rental agreement. There was also some apartment damage. All in all, the letter was accompanied by six Home Depot Receipts, a contractor invoice, and copies of the tax bills proving that taxes had increased. All the numbers matched. The grand total amounted to more than the deposit. Larry enclosed a politely worded bill for the difference.

The letter from Larry to Ashley was a good effort to disclose withholding and comply with the law. But it lacked key verbiage.

Larry’s Violations of the MA Security Deposit Law

The relevant law is MGL Chapter 186 Section 15B. It establishes a variety of rules, some of which must be followed or else triple damages are owed.

The most obvious violation was that Larry had failed to sign the itemized list of damages “under the pains and penalties of perjury.” Since this wording did not appear on the letter, Ashley was entitled to receive $8,925 in damages (three times the amount of the deposit), plus attorney’s fees.

There were many harder-to-see violations.

First, although Larry had obtained a conditions statement for the lease starting “year one,” the second lease starting “year two” was a completely different agreement with two different parties. Even though Ashley was a party to both, there was no conditions statement for the “year two” lease. No withholding was therefore possible.

Second, the law clearly establishes that withholding is permitted only for repairs above “reasonable wear and tear,” and that precise statements are needed to identify how damages exceed this threshold. Most of the invoice from Larry’s contractor pertained to general painting. Considering that the apartment had not been repainted in two years, it was arguable whether Ashley and roommates had done anything to the walls beyond “normal wear and tear.” For instance, there was no specific mention made of holes, whether they were for hanging pictures or they were very large, or where they were, or what process was used to patch them. It was all too imprecise.

Third, Larry was exposed to consumer protection triple damages. These would be filed not under the security deposit law but under MGL Chapter 93A.

First of the consumer protection issues was the water bill. Larry was not permitted to charge Ashley for water because he did not have a valid submetering addendum in place when she first rented from him. Nor was he permitted to charge for snow, which was actually a fine levied against him by his town for failure to maintain the sidewalk, and which Ashley had not agreed to pay in writing. Finally, the contractor Larry hired to repaint also performed certain renovation activities, including rehanging doors, but he was not a licensed Home Improvement Contractor. Arguably any of these things would have discredited Larry in court and resulted in additional triple damages. Certainly they would have added to Ashley’s attorney’s fees.

Of final note: the receipts submitted for materials purchased at Home Depot included a variety of items that could not be traced to repairs, including a 20 oz. coke.

A Law Made to be Unreadable

With Mike’s advice, Ashley was able to point out Larry’s mistakes and make a strong claim that she was owed her deposit back. She wrote Larry a polite email establishing a firm deadline by which he could return the deposit. In this letter, Ashley acknowledged $150 of Larry’s withholding that she believed was justified, and she cited MGL Chapter 186 Section 15B to argue with the rest.

The law as written is not lay-readable. Larry could not understand the complicated security deposit law clearly enough to see that Ashley was right. So he hired an attorney, and he missed the deadline Ashley had set. Ashley then retained her own counsel.

When Lawyers Get Involved…

If you want to understand why the laws are what they are, you need look no further than how the lawyers get paid.

Larry paid his lawyer to explain the law to him. Larry’s lawyer explained that Ashley had claims in excess of $10,000, then called Ashley’s lawyer to beg them to settle. Ashley’s lawyer agreed to settle as follows: a full return of the deposit, less the $150 trash fee, plus $200 per roommate for their trouble ($3,625), plus attorney’s fees, which totaled $2,000. That was Ashley’s attorney. Since this story comes to us anonymously from Ashley, it is unknown how much Larry paid his attorney. But suffice it to say, the landlord lost thousands, the tenants made hundreds, and the attorneys made thousands each.

The End of Ashley’s Security Deposit Story

Now we know how Larry, a Massachusetts landlord who thought he’d be getting $3,463 from his tenants’ security deposit, ended up paying them $6,000 and probably thanking his lucky stars.

The moral of the story is: common sense is not enough to succeed as an owner in Massachusetts. You need to understand the law well enough that you would decide to invest elsewhere, or else to avoid those features of the law, like security deposits, that create so much exposure for us.