Should Natural Gas be Banned in New Construction?

| . Posted in News - 3 Comments

In July Berkeley, CA became the first municipality in the country to ban natural gas infrastructure in new construction (effective January 1, 2020). Meanwhile in colder Massachusetts, natural gas continues to be the go-to choice for developers, new construction, and many renovations. Was it right to ban natural gas in California? Should natural gas be banned here too? This article considers the motivations of banning natural gas in new construction and the likely positive and negative impacts.

Why We Use Natural Gas

When it comes to home heating and cooking, natural gas has been dominant for the last decade.

Natural gas is cheap, and thanks to the application of new methods to extract gas from shale, it is an historically cheap fuel.

The appliances that use gas are reliable, as it burns without much residue. Gas stoves, boilers, and water heaters require minimal maintenance. And they are powerful. A single gas boiler can provide 80,000 BTU’s, capable of taking pipes and buildings quickly from cold to hot, even when uninsulated.

Natural gas fixtures are affordable and quiet. Gas stoves are used in professional restaurants and higher-end homes, and cost little more than electrical stoves on a feature-by-feature basis. Gas boilers are now so efficient their exhaust gas exits at temperatures safe for plastic pipes. No masonry or chimney is required.

Overall, natural gas has been a key enabler for many households and businesses that otherwise would be burdened by high heating and maintenance costs. So why would anyone want to outright ban natural gas?

Stated Motivations for the First-in-the-Nation Ban on Natural Gas

The ban was adopted July 7, 2019 in reference to a November 11, 2016 document detailing the reasons. Primarily, it’s climate change.

Berkeley noted that natural gas from buildings was producing 36% of their greenhouse gas emissions. They felt that continuing to permit new natural gas service was incompatible with state and local targets to reduce emissions 80% below 2000 levels. They also noted that it was not feasible to wait for California to address natural gas from buildings, as their local use of it was so much higher than the state average (8% of emissions state-wide, vs 36% locally).

Berkeley California, in this shot appears to overlook San Francisco. The major factor in Berkeley’s decision to ban natural gas was climate, although the danger associated with seismic disruption to gas lines, and resulting earthquake-induced fires, also mattered.

Why Natural Gas is a Climate Problem

Natural gas is the common term for a mixture of gases, primarily consisting of methane. Methane’s chemistry is such that, when in the atmosphere, it traps heat that otherwise would be radiated out into space. The range of methane’s likely contribution to global warming overlaps that of carbon dioxide. And worse than carbon dioxide, the quantity of which has increased 50% since pre-industrial times, the quantity of atmospheric methane has more than doubled.

Methane emissions from our natural gas system are non-trivial, as leaks are extremely numerous. In Massachusetts alone, as of the end of 2018, we had over 16,000 active natural gas leaks from our pipes.

Leaked, unburned methane works its way straight into the atmosphere, occasionally damaging trees and crops along the way, and contributes to global warming at a rate that is pound-for-pound 84 times more potent that carbon dioxide will be over the next 20 years.

Even if all this natural gas were burned the way we intended, the combustion product is carbon dioxide, which is the main greenhouse gas problem. Despite marketing spin that organizations like ISO New England use to describe natural gas as a “lower emitting” supply like solar and nuclear, natural gas is categorically different from solar and nuclear. Natural gas produces greenhouse gas emissions. Solar and nuclear do not. Gas is “cleaner” only in the sense that it doesn’t also produce nitrous oxides or soot at the same rate as coal or oil.

Why Natural Gas is More than a Climate Problem

Natural gas has three major issues beyond climate change. It produces carbon monoxide in excess of safe household limits, it exacerbates fire hazards, and the utility company can blow up your building with it.

Natural gas is a combustible, and combustion is a chemical reaction that produces toxic byproducts. Although in theory perfect combustion of natural gas produces only water and carbon dioxide, in practice combustion is never perfectly complete. For instance, during the transition from cold to hot, gas stoves burn incompletely. They temporarily produce more carbon monoxide than is safe. The reason your CO detectors don’t trip is because they are designed to ignore transiently high values produced by stoves. The carbon monoxide eventually dissipates. But it can enter your bloodstream, and like lead dust, there is no helpful amount of carbon monoxide. Toxic gases are inhaled in small quantities every time a chef turns on their gas stove.

Natural gas increases the lethality of a household fire if one starts. The most common cause of all household fires in Massachusetts is cooking. (Note that the most common cause of lethal fires remains smoking.) The Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General, one organization of many that tracks fire statistics, measured that gas stoves are 15% more likely to produce a fatal fire than an electric stove. For anyone who has experienced a house fire, this will make immediate sense. When a gas line ruptures due to heat, it takes what might have been a contained fire and flamethrowers it into a total catastrophic loss.

Finally, natural gas can explode. Detonation is a unique phenomenon from combustion, and requires gas and air be mixed to a specific ratio. When a spark is applied, the resulting “fire” happens essentially everywhere at the same time, like a bomb. Each gas-connected house is connected to a high-pressure network operating somewhere around 100 psi, and depends for its safety on the pressure stepping down one hundred times, to roughly 1 psi, without any leaks along the way. Any overpressure that leaks uncombusted gas into a contained space can create a gas-air mix at the detonation point. Despite the best efforts of tens of thousands of professionals who perform safe gas work every day, the Lawrence gas explosions are just one recent example of a history full of explosions.

A theoretically perfect combustion of one methane molecule (CH4) in air (two O2) produces only heat, carbon dioxide (CO2) and two water molecules (H20). Incomplete combustion produces carbon monoxide instead of carbon dioxide. Non-methane gas constituents produce other byproducts, including soot.

What the First-in-the-nation Berkeley Ban Does

The Berkeley ban is short. It prohibits natural gas installations in any new building, residential or commercial, where an alternative all-electric design exists. For instance, if you could heat and cool a house with heat pumps, heat the water with a heat pump, and install an electric or induction stove, you can’t have gas.

There is a public interest exemption. This will surely be used to permit developers to continue installing gas service where affordable housing units are included. (Affordable housing is in the public interest, after all, or so it may be argued.) Presumably the public interest exemption may also be used to build public buildings, like police stations, with gas. But these exemptions should not be granted. As we have discussed elsewhere, for instance in our deep energy retrofit article, the technology now exists to avoid natural gas in all new construction.

Massachusetts Reliance on Natural Gas

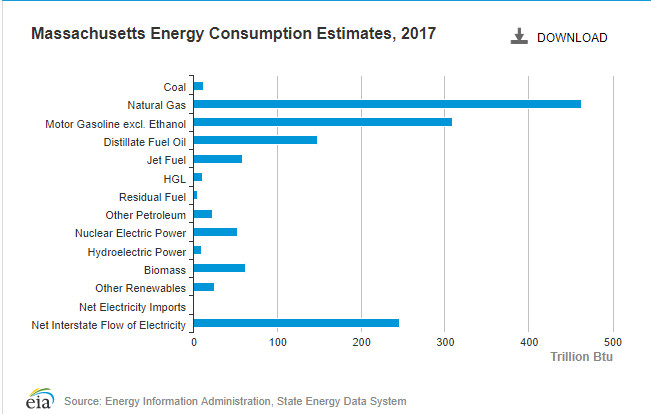

Unlike most of California, Massachusetts has cold winters (USDA zone 7 or lower compared with California’s zone 8 or higher). In 2017, 32% of all energy consumption state-wide was natural gas, and 60% of electricity production was natural gas. We use natural gas for heating and even more extensively for electricity.

We want to use natural gas so badly, in fact, that demand has exceeded capacity for some of our pipes. In a growing number of regions, new gas customers are no longer permitted. Moratoriums on hookups have been imposed on the outer cape and in parts of Franklin, Hampshire, and Hampden counties for years.

Natural gas companies have argued that the lack of pipelines into these regions are an absurd policy outcome. They say that dual fuel systems that flex from natural gas to oil will produce twice as much greenhouse gas as if they had been given natural gas. They say it’s better for us to add pipeline capacity.

What the natural gas industry doesn’t say is that natural gas produces infinitely more greenhouse gas than solar, nuclear, hydro, wind, or geothermal. These are all zero emission technologies that generate electricity. It is a critical juncture for Massachusetts: do we build more pipes or do we back away from this fuel source?

The Alternative to Natural Gas Heat: Heat Pumps

Thanks to heat pumps, electricity can now be used to move heat three- to five-times more efficiently than old electric baseboard systems.

As we have written about before, heat pumps are now cold rated for Massachusetts winters, which means they offer feasible all-season alternatives to combustion.

Heat pumps can be non-renewable, if their electricity supply comes from fossil fuels. Or they can be fully renewable, if for instance they are powered by solar. Solar is not required for heat pumps to be renewable. Massachusetts electric customers can elect a 100% renewable grid source at rates comparable to natural gas generation. This renewable source may be solar, hydro, wind, or other.

For a natural gas system to be replaced by heat pumps, the premises need to be both well insulated and air-sealed. Heat pumps cannot keep up with winter heating load in a leaky building. This makes retrofit difficult, but new construction is a simple matter.

The installation and maintenance costs of heat pumps remain at a disadvantage relative to natural gas systems. Heat pumps currently tend to be as expensive as furnaces. They tend to have half the service life, and greatly increase the penetration of plumbing in a building (read: leaks). The technology is new and maturing rapidly, though, so actual service life remains uncertain. Newer models might reasonably be expected to last longer than the ones for which we have data. A good design will plan for access to any part of the system that may leak.

The Alternative to Natural Gas Cooking: Induction

Compared to heating, eliminating natural gas in cooking is easy. Electric resistance ranges have been on the market for decades and will get the job done cheaply. Electric stoves, however, are viewed dismissively by serious cooks. Their burners have residual heat, making it a slow process to lower the heat on an over-temp pan. And this same phenomenon makes them slow to heat up from cold, as well. Cooking takes longer and burning may be more frequent.

Thanks to induction technology, though, there is now an electric option that by most accounts performs superior to all gas stoves. Electric induction ranges do not send a large percentage of their energy off to either side of the pan as hot air, as gas does. Instead, they use special ferromagnetic cookware to generate electrical eddy currents in the pan itself, heating pans in a fraction of the time of even the best gas stoves. Induction compatible cookware sets can be purchased for as little as $100.

Likely Impact of Banning Natural Gas in Massachusetts

There is precedent for successfully banning greenhouse gases. For instance, chlorofluorocarbons (CFC’s) have already been phased out, except in essential uses. And Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFC’s) are going away, too. Can we likewise ban methane?

Although the technology exists to heat and cool homes and water without natural gas, a number of political obstacles make a state-wide or national ban problematic.

First, there is substantial vested interest in natural gas infrastructure, both from a capital and a labor point of view. Until we are prepared to help investors and workers move their money and skills into other industries, we will likely continue to see advocacy for expanded natural gas infrastructure.

Second, there is a substantial public benefit to cheap winter heat. It’s easy to forget in our world of modern conveniences that New England is a harsh place, unsuitable for unsheltered or under-sheltered human habitation year-round. We have 15,000 Commonwealth citizens experiencing homelessness every year. In addition, we need hundreds of thousands of new units to be built over the next decades to meet market demand. Adding any additional operating costs to shelter or capital requirements on new housing would be counterproductive for these particular goals.

Alternatives to a Natural Gas Ban

Typically outright bans produce black markets, where would-be purchasers find illicit means to obtain the desired outcome. It’s hard to imagine a black market for natural gas. Someone would notice you digging a connection to the main, or running a pipe from your neighbor’s house. But it does happen and can have fatal consequences.

A free market approach would involve finding a way to make heat pumps more affordable than natural gas over the system lifetime. This requires technology that is not available, or at least not known to MassLandlords. Then it would be necessary to educate the homebuilding and renovating population. All of this would take time.

A carbon tax that adequately penalized greenhouse gas emissions from a building’s gas infrastructure could create the right level of incentive to drive alternatives. For instance, we might determine that a new three-unit building would have $40,000 of climate impact owing to its natural gas usage the next 30 years (a made-up number, impossible to know with certainty, but let’s say for the sake of argument this is the applicable carbon tax). Then owners could choose to pay that tax for whatever perceived benefit lies with natural gas. Or they could choose to put their money into heat pumps instead. With this level of tax, and heat pump costs being what they are, owners choosing heat pumps would come out ahead.

Natural Gas Ban Conclusion

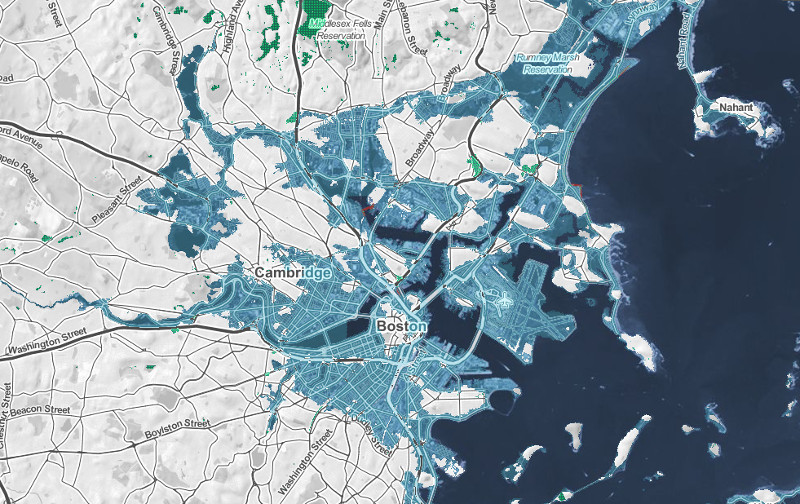

Berkeley was the first, and will likely not be the last municipality in the US to ban the installation of new natural gas pipes. Regardless of whether we in Massachusetts follow suit, we will pay the cost, if not in terms of insulation, heat pumps, and economic realignment, then certainly in terms of sea level rise.

Climate Central’s map of the NOAA “extreme” scenario for 2100 shows 8 feet of mean sea level rise, before accounting for storm surge. This scenario displaces at least 172,000 residents.

External Links

Three adult family members found dead in Nahant home with elevated carbon monoxide levels, officials say, Boston Globe, 2024 Jan 8

Over 20 people injured in apparent gas explosion at Texas hotel, Guardian, 2024 Jan 8

Members fund our work to find consensus and stop emissions.