Rent Control Reform in Cambridge: 1991 Report Paints Grim Picture of Stabilized Housing

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

The article on this page refers to past rent control. Two years ago, we fought and helped derail Boston Mayor Wu’s rent control proposal, and we are determined to quell the current initiative, too. We are doing all we can to avoid a return to the disastrous rent control policies of the 1970s-90s.

By Kimberly Rau, MassLandlords, Inc.

The year 1990 marked the twentieth anniversary of rent control in Cambridge, having been first enacted in 1970. In February 1991, the city’s subcommittee on rent control published a study to address problems with the rent stabilization system. What resulted was a 38-page document that, while in support of rent control, shed light on glaring issues.

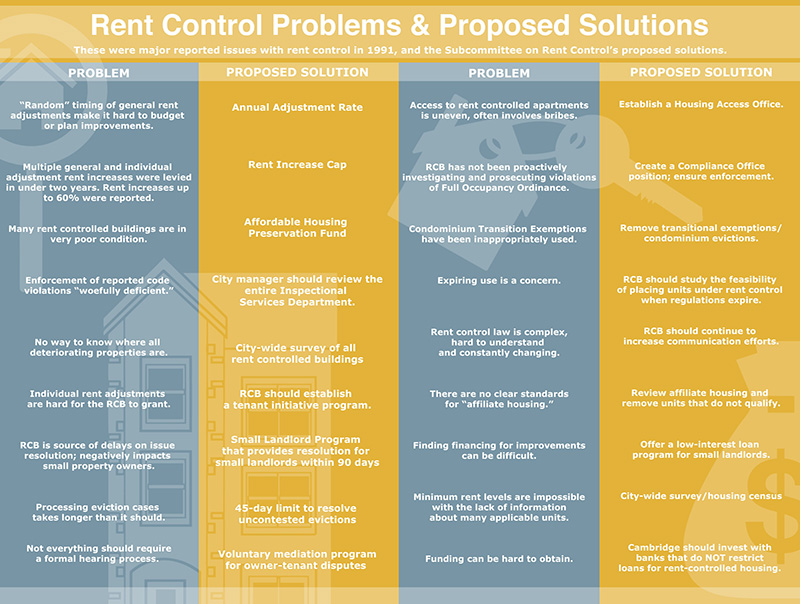

The full list of the 18 biggest concerns or issues with rent control in Cambridge, from a study released in 1991, along with the Rent Control Subcommittee’s proposed solutions. Rent control was abolished in the city in 1994, before many, if any, of these solutions could be attempted. Concerns and solutions have been edited for length.

“In the face of daunting odds, the people of Cambridge have made [rent control] a success – not an absolute success, but a significant one,” the report’s introduction states. “Many people remain unsatisfied with the present rent control system and often for good reason; it is with these good reasons in mind that the City Council Subcommittee on Rent Control worked to reform the rent control system. It is in that same spirit that this report is written.”

The report, authored by subcommittee staff member Richard Thompson Ford, was designed to address the biggest issues that could disrupt rent control. The subcommittee held 15 meetings in fall 1990 with time for public discourse on rent control – meetings that, per the report, “were often marred by volatile outbursts and posturing of various sorts.”

The result was a report that listed 18 of the biggest complaints about rent control in Cambridge, and a list of proposed solutions by the subcommittee.

In this article, we look at some of the biggest problems with rent control in Cambridge in 1991. It’s worth noting that, though the report attempted to provide solutions for these issues, rent control was repealed by voter referendum in 1994. Many of the proposed solutions (the creation of new committees, citywide inspections, loan infrastructure) never had time to be properly implemented. Had they been, there’s no guarantee the proposed solutions would have worked. For a full list of all the issues and proposed solutions, see our infographic.

Bribes, Insider Knowledge and Lack of Access Kept Rent-controlled Units Out of Reach for Disadvantaged Populations

During this time, it was no secret that there were individuals occupying rent-controlled housing who had no business doing so. Most famously, Cambridge mayor Kenneth Reeves lived in a $421-a-month unit ($421 in 1991 had approximately the same purchasing power as $820 in 2021). However, the 1991 report noted that access to rent-controlled units was more complicated than merely discovering a handful of well-off tenants.

“Several identifiable groups of tenants are underserved by the City’s rent-controlled housing,” the report stated. “These groups include African Americans, families with children, recipients of public assistance and the elderly.”

All four of those groups were underrepresented in the rent-control market, but especially Black individuals. “Whites, Hispanics and [non-Black people] of other races all use rent-controlled housing as their primary source of less-expensive housing, and subsidized housing as their secondary form of less-expensive housing,” the report said. “[Black people] are not represented as one would expect, all things being equal, in the rent-controlled market.”

The report also noted that 26% of subsidized units had elderly residents, but only 7% of rent-controlled units had elderly people living in them. Families with children lived in 32% of rent-controlled units, but in 58% of subsidized units and half of the non-controlled homes in Cambridge.

Why were these groups so underrepresented? The report notes that it was “apparently the closed nature” of the rent-control market, and went on to state that many rent-controlled units were snapped up due to insider knowledge and bribes.

“[I]ndividual rent-controlled apartments rent quickly with a financial ‘tip’ to the building superintendent or direct payment to the landlord or departing tenant…it is seldom, if ever, that a rent-controlled unit is advertised in local newspapers.” This is not a new phenomenon. In 1985, Heikki Loikkanen published a study titled “On Availability Discrimination Under Rent Control,” which examined landlord behavior when searching for tenants. Among other findings (namely, to a point, landlords will hold a unit empty rather than rent to an “undesirable” tenant), Loikkanen discusses how bribes, called “key money” in Finland, factored in under rent control. The answer? Even “preferred” potential tenants would offer bribes; “non-preferred” tenants would have to offer larger bribes to be considered.

The fact that fewer individuals in the aforementioned groups lived in rent-controlled apartments meant that others in those groups were less likely to know about a unit and therefore less likely to be able to bribe the right people.

“Without [Black people] who can provide information to their friends and relatives about the availability of units, other [Black people] are less likely to have equal access to those units,” the report stated. “A real estate market which denies equal access to individuals without their fair choice is discriminatory.”

Dilapidated Housing Units Threaten Rental Stock

One issue that resulted in several proposed solutions was the condition of rent-controlled units in Cambridge. Some were in disrepair while others were reportedly being upgraded just so landlords could increase the rent.

“While several tenants expressed concern about ‘gold-plating’ by several landlords, equally concerning were comments about very usable fixtures being replaced for the possibly sole purpose of increasing rent.”

The report suggested the Rent Control Board work with landlords to develop five- to 10-year repair/replacement plans that would spread out capital improvements and rent increases, along with ensuring buildings were kept in good repair.

And while some were complaining about unnecessary renovations and upgrades, it’s clear that many more buildings were not reportedly in “good repair.”

“It is clear that many buildings require significant work if their habitability is to be maintained,” the report stated, referencing a 1990 report by Andrea Devine, which determined that “more than 50% of the low rent units [surveyed] are in wretched condition; they have been neglected by their owners, and they are occupied by tenants who seem to be able to afford no more or little more than the rents they are currently paying.” (When writing this article, we attempted to find a copy of this report, but it appears that it was never digitized.)

Further, the Department of Community Development (DCD) also reviewed the problem and concluded that without “significant capital reinvestment,” Cambridge was at risk of losing rental stock.

“Buildings like Hampshire Place, where physical problems with the property are leading to increased vacancies and attempts to demolish the properties will be more common,” read a quote from a DCD memorandum from November 1990.

“Tenants…frequently pay general adjustments without benefit of improved conditions,” the 1991 subcommittee report stated.

The subcommittee proposed the creation of an Affordable Housing Preservation Fund, paid for by non-exempt tenants on a monthly basis at a rate of 2-5%. The fund would be used to provide grants and loans to owners who needed to preserve their deteriorating properties.

Code Inspection Efforts are “woefully deficient.”

Under Cambridge’s rent-control system, landlords could expect general rate adjustments to the rent. However, when the tenants were notified of the increase, they were also informed that if the apartment was not up to code, the increase could be deferred or denied if they filed an Affidavit of Conditions.

So, what happened when tenants did complain about deteriorating conditions or other code violations in their rent-controlled housing?

“The Sub-Committee heard repeated testimony indicating…enforcement efforts are woefully deficient…the additional step of aggressively pursuing code violations to assure code compliance is rarely effective.”

Tenants said that when they reported code violations, point inspectors from the Inspectional Services Department (ISD) would visit the unit and record the violations. But, tenants stated, they had to point out the code violations and request that inspectors write them down. At that point, the tenant would receive a copy of the citation, and a copy was sent to the building owner. If the owner did not respond, a long waiting game would commence.

“Experience confirms that once the cited violation is pursued in court by the legal representative of the Inspectional Services Department, more than a year later the same uncorrected violations still exist,” the report continued, noting this wait time was unacceptably long.

The report recommended Cambridge’s city manager review the organization of the ISD, stating that there was “sufficient indication” that the training of building and health code inspectors was not adequate for recognizing all code violations.

Further maddening, the entire process seemed mired in redundant actions on the part of the ISD.

“Tenants state that after reporting violations, their interest is in having the violations corrected. They do not want to receive multiple follow-up visits to ‘discuss’ the violation,” the report stated, adding that tenants had the perception that the ISD was relying on them to monitor the status of the reported violations.

“It is unclear why as many as six or seven different inspectors appear to monitor the same violations, often visiting in groups of two or three…[t]he current level of departmental dysfunction…should not be permitted to continue.”

Conclusion

These were just three of the biggest issues surrounding rent control in Cambridge, which finally halted in 1994. Add in a Rent Control Board that seemed to arbitrarily permit rent increases, drag its feet with evictions and take a lackadaisical approach to correcting myriad tenant issues, and it becomes clear why rent control may look good on paper, but ultimately does not help the populations it seeks to serve.

"The average rent adjustment hearing takes six months. Unnecessary hearings drain the time and resources of owners, tenants and the city." p. 23

When writing this story, we attempted to see which, if any, of the subcommittee’s suggested reforms were implemented in the nearly four years before rent control was abolished statewide. We were unable to confirm that any had been adopted. This is troubling. If the state is looking to allow cities and towns to adopt and oversee their own rent control policies, and this is the longest-standing example that municipalities have for reference, Massachusetts housing could be in for a rough future.