Ranked Choice Voting, Defeated Statewide, Not Going Away

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

When Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) was rejected by Massachusetts voters on November 3, 2020, it was a setback for housing providers and businesses in the state. The continuation of our state’s Plurality Voting System means that legislative candidates will carry on with campaigns appealing to small constituencies that they wager will win them just enough votes to top their competitors.

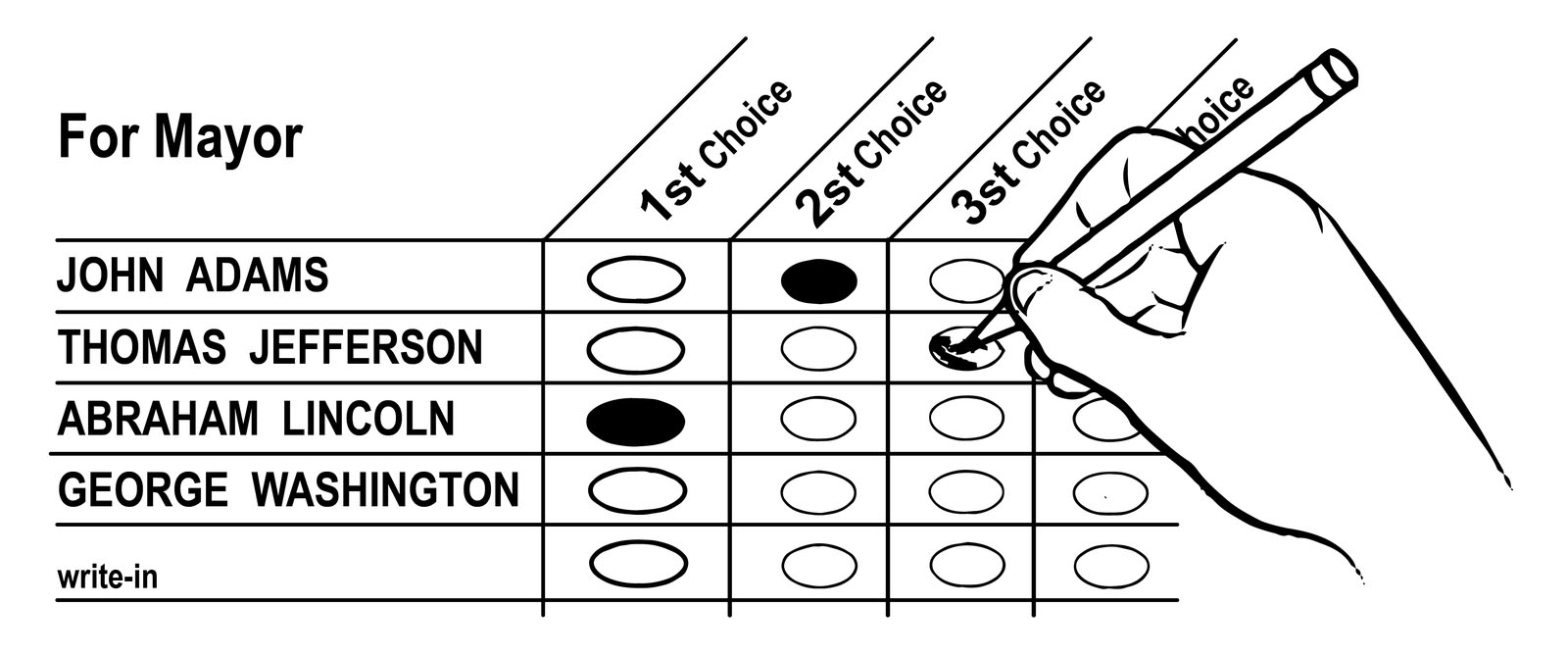

Ranked choice voting allows voters to list their ballot choices in order of preference. CC BY-SA MassLandlords

As a voting bloc, landlords lose in this structure because we are vastly outnumbered by renters. And though there are common interests among renters and landlords, politicians seem to treat these as disparate constituencies. So in our current system it makes perfect sense for a legislative candidate to appeal to renters and renter advocates – without regard for landlords’ interests – in order to win their votes and carry them to a plurality. Once in office, they are duty-bound to make policies that favor the constituencies that elected them.

That’s exactly what Rep. Mike Connolly, a Democrat representing Cambridge, did. Then he went on to propose a rent cancellation bill that gained strong traction and would have driven many landlords out of the industry. Obviously, that’s not a good long-term solution for the state’s housing crisis.

Plurality Voting’s Impact on Landlords and Housing

The MassLandlords Board of Directors endorsed the Ranked Choice Voting initiative on the state ballot in November partly because of the voting system’s potential to elect legislators that appeal to a broader constituency, including landlords.

The current plurality voting system in place in Massachusetts – and most other states – requires the winning candidate only to receive the most votes, regardless of whether those votes constitute a majority. As a result, candidates frequently appeal to a narrow constituency, such as renters, knowing that the backing of that constituency can win the election, sometimes with as little as 20% to 30% of the total vote. That means, in many cases, 70% to 80% of voters voted against the legislator who represents them.

We saw the result of this system in 2020 when legislators loyal to a constituency of renters and renter advocates succeeded in enacting one of the nation’s most inequitable eviction moratoriums in reaction to the coronavirus pandemic. The moratorium provided little recourse for small landlords, rendering unnecessary financial strife and putting many out of business, while doing nothing to address the long term.

A Case in Point

This scenario was repeated recently with a special election, on March 30, 2021, in the 19th Suffolk District, representing Winthrop and part of Revere, to fill the vacated seat of former House Speaker Robert DeLeo. Trump supporter and self-described moderate Jeff Turco won the four-way Democratic primary with 36% of the vote. Turco has publicly espoused some views that run counter to the majority of his district. Nearly two-thirds of the electorate voted against him in favor of another candidate. Yet Turco went on to win the general election, soundly defeating an unenrolled candidate, Richard Fucillo, and Republican challenger Paul Caruccio.

In the four-way primary, labor organizer Juan Jaramillo garnered 30% of votes, boosted by the progressive electorate in the district, which had supported DeLeo. But, having carved up the vote with the other two candidates, who totaled 34% between them, it wasn’t enough to overcome Turco’s plurality.

This is how a district ends up being represented by a legislator with whom they don’t align on some major stances. It’s impossible to say that the outcome would have been different had ranked choice voting been in place. But given the progressive lean of the district, it’s at least plausible that Jaramillo would have taken a strong share of the other candidates’ votes and gained the 6%-plus necessary to have won the primary with ranked choice voting.

Winning Elections with Less than Majority Vote

The March 30 election wasn’t the only contest this year with an outcome not representative of the majority of voters. The 4th District, primarily including Newton and Brookline, held a similar primary to fill the congressional seat of Representative Joseph Kennedy III. This resulted in the election of Jake Auchincloss, a one-time Republican who helped elect Gov. Charlie Baker. Auchincloss won a crowded Democratic primary contest with only 22.41% of the vote before besting Republican candidate Julie Hall in the general election.

The primary was stacked with eight progressive candidates who split the remainder of the vote. Jesse Mermell topped that list with 21.11% of the primary vote, losing by 2,000 votes following the discovery of a cache of some 3,000 votes after election night.

Looking further back, Rep. William Driscoll, Jr., a Democrat representing the 7th Norfolk District, won his 2016 primary contest with 21.37% of the vote, splitting with six other candidates. He ran unopposed in the general election. Joseph Boncore, a Democratic representative of the 1st Suffolk and Middlesex District, won a 2016 primary among seven candidates with 25.7% of the vote before running unopposed in a special election.

The Massachusetts legislature has more than a dozen legislators who won their primaries with less than a majority of votes before capturing general elections, in lopsided or unopposed races.

Ranked Choice Voting Redux

To revisit briefly, ranked choice voting is an election system in which voters are given the option to rank candidates in order of their preference. RCV requires a candidate to have a majority of votes in order to declare a winner. If no one gets at least 50% of the votes cast, the candidate with the fewest top votes is eliminated and that candidate’s votes are awarded to the front-runner, until someone has gained a majority and is declared the winner.

RCV would allow multiple candidates, such as those in Winthrop and Revere, to compete without canceling out each other’s votes and ending up with a default winner who doesn’t represent the majority of the district. It might also encourage candidates to run campaigns that appeal to a wider swath of voters rather than negative campaigns that seek chiefly to impugn their competitors.

Plurality voting, the most prevalent system across the nation, potentially waters down democracy by incentivizing practices like the gerrymandering of districts in order to concentrate an incongruous share of voters favorable to one party. A less fair election is the result.

Plurality voting also frequently has a dampening effect on voter turnout because parties, in an attempt to reduce the effect of multiple candidates canceling each other’s votes, may minimize the number of candidates, presenting voters with fewer choices.

Why Ranked Choice Voting Lost

Massachusetts voters rejected ranked choice voting in November 2020, by a 55% to 45% margin. Much of the opposition to the voting system concluded that RCV was too complicated, and that because of its complicated structure it would reduce voter participation. Other critics have decried a projected increase in the cost of elections with RCV. And some opposition claimed that RCV would increase likelihood of tallying mistakes or election fraud – an unsubstantiated claim.

The argument that RCV is too complicated is refuted by recent facts. Maine, which adopted RCV in 2016, saw 87% of voters there opt to rank their ballots instead of choosing just one candidate in the first RCV election. And in Minneapolis, where municipal elections use RCV, 95% of respondents said ranked choice voting was easy and intuitive.

But in a pandemic year, it’s difficult to educate voters and build local consensus for a referendum without the use of community forums, which were mostly not allowed during the 2020 campaign season.

“It was challenging to run a campaign during a pandemic,” Evan Falchuk, chair of the 2020 Ranked Choice Voting Committee and a former independent candidate for governor, recently told MassLandlords. “If you can’t organize, and sit with people, it’s hard to educate people. Because of the pandemic, we couldn’t organize.”

Will Ranked Choice Voting Come Around Again?

Legislative rules disallow ranked choice voting from appearing on the ballot for statewide vote again until 2026. But Falchuk points out that the issue is not going away.

“There are a lot of people out there who want to see this continue,” he said. The 2020 RCV campaign raised the profile of the issue and gained the interest of many voters who weren’t aware of it. “It really put RCV on the map for people in the commonwealth.”

Meanwhile, Falchuk noted, several Massachusetts municipalities continue the trend of adopting RCV systems for local elections.

Arlington is one. The town, whose voters opted for RCV by 63% in November, has begun the legislative process of adopting the system for its local elections with a town meeting vote. Other Massachusetts municipalities with RCV in place include Amherst, Cambridge and Easthampton.

The Arlington RCV campaign is spearheaded by the town’s Election Modernization Committee, chaired by Greg Dennis, who assumed leadership of the Ranked Choice Voting Committee from Falchuk.

“A key thing about RCV is that oftentimes in a town like Arlington, people are told not to run for public office because they are concerned about splitting the vote with another candidate,” Dennis told WickedLocal.com in March. “With ranked choice, you don’t have to be worried about that and the result is that more candidates can run for local positions.”

Ranked Choice Voting Continues Historic Trend

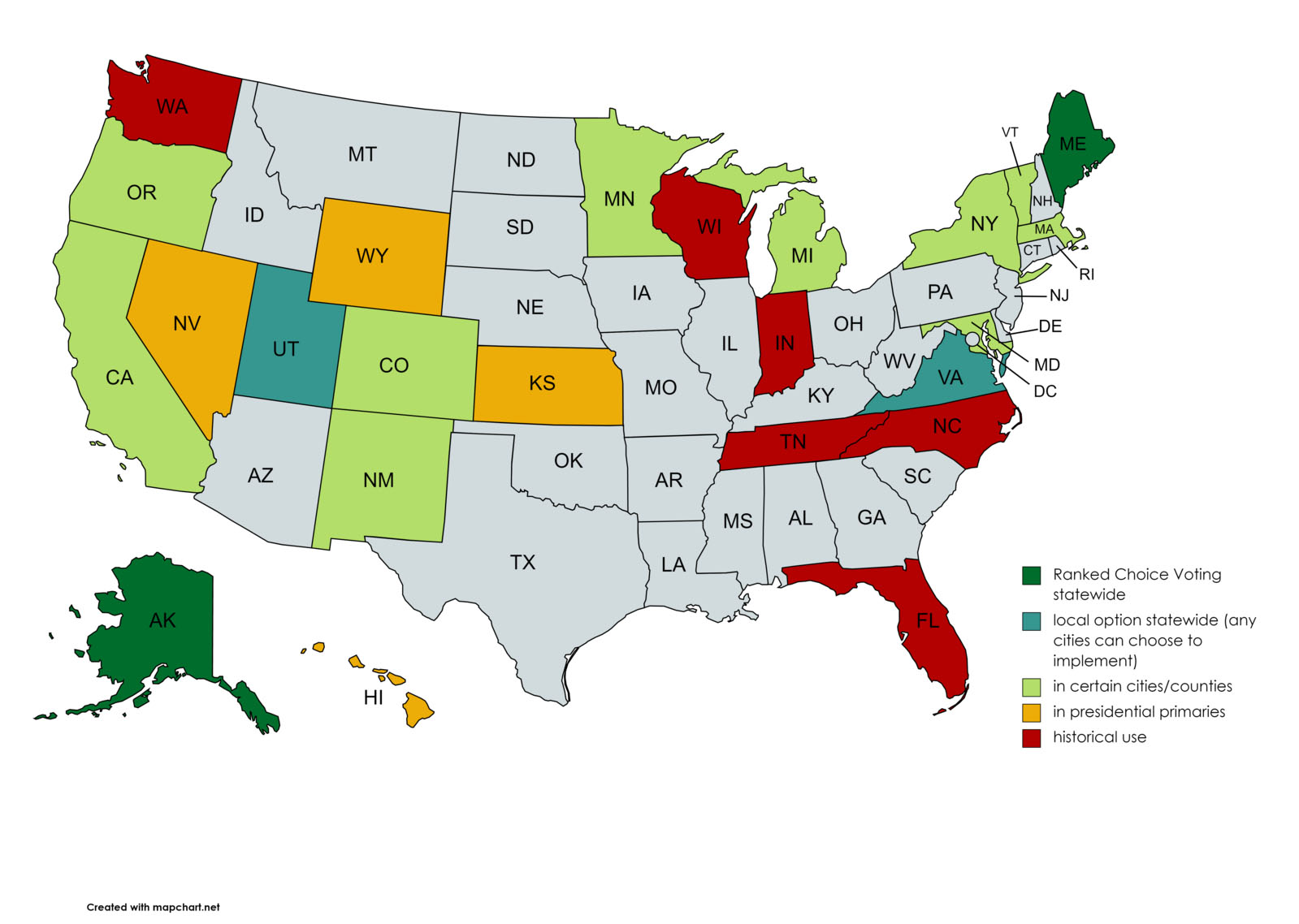

As this graphic illustrates, ranked choice voting is used in some fashion in nearly half the states in the nation. Image: CC SA-BY Wikimedia Commons

Massachusetts would hardly have been the first state or entity to employ RCV. Maine voters approved RCV in a referendum in 2016 and the system was in place for the state’s 2018 gubernatorial election, national primaries and congressional races. A lawsuit was filed by Maine Republicans claiming that the RCV system was not constitutional. The lawsuit was rebuffed twice by the state Supreme Court, and again by the U.S. Supreme Court in October 2020. Maine is now in the process of amending its state constitution to allow it to expand RCV to state congressional elections.

Further afield, Alaska narrowly approved RCV for general elections in November 2020. Municipalities in 13 states use RCV for some elections. Abroad, ranked choice voting is employed in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, India and a few other countries. And many corporations use RCV to elect their boards.

As this illustration demonstrates, ranked choice voting is a simple process of listing your choices for each candidate on the ballot in order of preference. Image: CC SA-BY Wikimedia Commons

Historically, the United States has seen a gradual, if uneven, trend toward greater voter inclusion and representation. Since the republic began with highly restrictive voting, exclusive to white male landowners, laws over our 244-year history have broadened voter representation and the right to vote, even considering the recent spate of suppressive voter identification legislation in some states.

This voting system evolution makes sense. As the population of the United States has expanded demographically, its voting laws and inclusion have had to grow with it in order to respond to the societal needs of an ever-changing populace. When the country cast its first votes, its lawful electorate and needs were much more homogenous, and policies were proposed to meet those simpler, more unified demands (primarily those of white male landowners).

Today’s United States is a welcome potpourri of cultures, backgrounds, outlooks, beliefs, socioeconomic diversity and needs. Our voting methods must change to amalgamate wildly different perspectives into consensus solutions, lest we end up permanently whipsawing back and forth depending on who ekes out a plurality to wield power over the rest.

We see the results of the more restrictive system we have in place. Housing crises and homelessness on the rise nationally, with no visionary solutions able to gain traction. Governmental gridlock and rampant negative political culture. It’s not a sustainable model for a highly functioning democracy. Our voting structure needs to evolve in order to allow and enable the most inclusive participation possible.

Ranked choice voting is a move toward that objective.