Matthew Desmond’s ‘Evicted’ 6 Years Later: Good Copy, But Does It Tell the Whole Story?

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

By Kimberly Rau, MassLandlords, Inc.

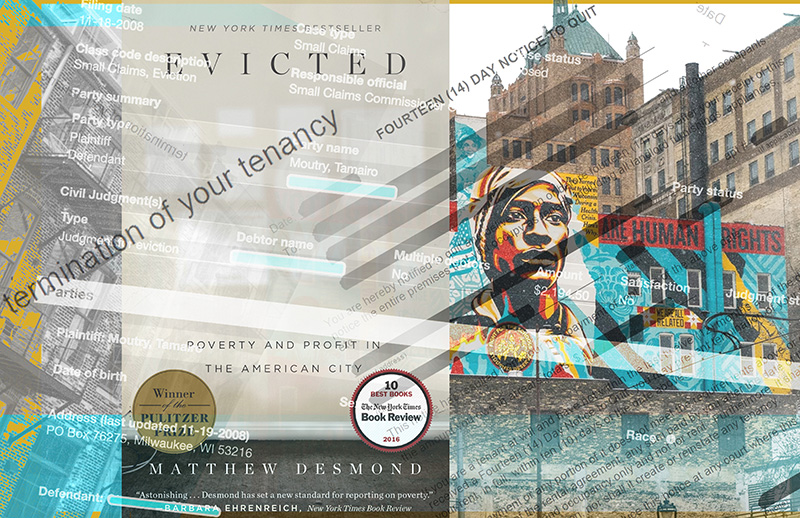

“Evicted,” published in 2016 by Matthew Desmond, forced Americans to look at the housing crisis in their own backyards and changed how we talk about eviction. However, we recently took another look at “Evicted” and found a compelling story, but also ended up with more questions than answers surrounding how to fix the problem.

“Evicted” by Matthew Desmond tells a compelling story of eviction and low-income tenancy in Milwaukee, and by extension, America. However, the broad solutions proposed in the book leave us with more questions than answers, and wanting more. License: CC by SA 4.0 MassLandlords, derived from Unsplash

“Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City” is an ethnographic study in poverty and eviction in Milwaukee, Wis. Between 2008 and 2009, Desmond lived in Milwaukee, first in a trailer park, then in an impoverished neighborhood, following eight families and multiple landlords as they navigated surviving in the city.

The response to the book-length study was huge. It won a Pulitzer prize. Desmond was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant and founded the Eviction Lab in 2017, which attempts to provide nationwide data on eviction. Desmond is frequently invited to speaking engagements to discuss his work.

But as eye-opening as Desmond’s book is, and as much as we can agree that eviction and stable housing are major issues in America, we at MassLandlords feel both the book and the work at Eviction Lab are over-simplified and do not paint a complete picture of rental housing nationally.

The Hood May Not Be So “Good” for Landlords

One of Desmond’s chapters in “Evicted” is titled “The Hood is Good.” While Desmond follows eight families in his book, and states that he talked to 30 landlords, the landlord information he chooses to include comes from just two individuals. One is Tobin, the operator of a trailer park. The other is Sherrena, a landlord who lives the high life while primarily renting out terrible-quality homes in Milwaukee. Both landlords, just like the renters Desmond profiles, are given pseudonyms.

Sherrena drives a nice car and sometimes wears a fur coat to collect her rent. Desmond tells us that rental units in low-income neighborhoods can be more profitable than those in wealthier areas, often because people hard on their luck are less likely to complain, fearing eviction. When one of Sherrena’s units catches fire, killing an infant, she is with her husband at the casino when she is notified of the incident. She buys foreclosed homes and rents them out, and dabbles in rent-to-own setups, helping people raise their credit scores to buy homes from her. (She also admits many of those people ended up losing their homes afterward.)

Sherrena tells Desmond that “the hood is good.” Desmond uses her words and his experiences following her to paint a picture of those who profit off the have-nots.

We have no reason to believe that Sherrena’s lavish lifestyle was fabricated. Desmond specifically says his fact checker talked with her, and corroborated her story. (This fact checker signed a non-disclosure agreement, so we were unable to talk to her for this article.)

But does that tell the whole story?

No. Through house deeds and court records, all publicly available, we learned Tamairo Moutry was the landlord Desmond shadowed and called Sherrena. This was confirmed by sources who worked on background for this story along with court records and information provided in Desmond’s book.

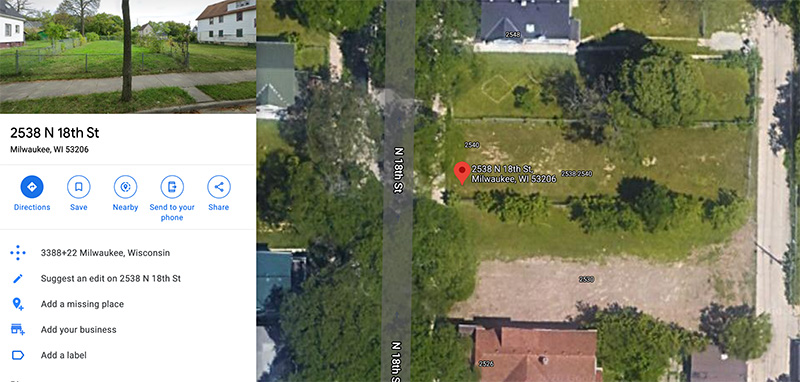

The aforementioned fire was one of several ways we were able to connect Moutry with Sherrena in “Evicted.” The fire occurred at 2538 N. 18th St. in February 2009. The house has since been torn down, but eviction filings from 2008 as well as from 2009 list Moutry as the landlord for the property, which had more than one housing unit on it. Tax records show the city of Milwaukee now owns the lot. (In 2008, both Moutry and a man named Jerome Harleaux were filing eviction cases and using the same post office box for their addresses. We believe this may be Moutry’s spouse, who was also profiled in the book under the pseudonym Quentin. Harleaux, too, filed evictions: one in 2006, two in 2008, and at least one in 2013 and 2015. The address he lists for those also matches a street address Moutry occasionally had attributed to her in court filings.)

Regarding the fire, both the news and “Evicted” reported that the unit did not have operational smoke detectors. No charges were filed against the unit’s landlord, though a source who spoke on background stated the mother of the baby who died allegedly settled privately for an undisclosed sum of money.

This is the plot of land for 2538 N. 18th St. It once held two of the houses Sherrena/Tamairo Moutry was the landlord for during Desmond’s time in Milwaukee. One of the homes on this lot was also the site of a major fire that killed an infant during that time. Source: Google Earth

Was the “hood” so “good”?

In the years following Desmond’s research, Moutry was in court multiple times, and not for evictions. The city of Milwaukee was after her for taxes owed, and creditors were seeking garnishments.

Desmond (who has not publicly confirmed Moutry’s identity) has never issued an addendum to this that we could find, though in his speaking engagements he continues to use the example of landlords profiting off of desperate people as an example of how the rental system needs help. Even if Desmond does not name Moutry directly in these talks, by referencing his book, we automatically connect his words to Sherrena. Therefore, Moutry’s actions in the book are still held up as examples of all the ways landlords profit off eviction and renting uninhabitable places. He does not mention the number of times Moutry was in court for non-eviction-related issues, including for taxes she owed as far back as 2010, or the foreclosures (2016, 2016, 2018, 2019).

In April 2016, a month after “Evicted” was published, Moutry made the list of Milwaukee’s top delinquent property owners, reportedly owing $15,000 in building code violations alone. These were not reported in “Evicted,” despite the fact that the city initially filed against Moutry in court a full year prior to its publication, in January 2015. The last Milwaukee eviction Moutry filed that we could find was in 2010.

As far as we can tell, Moutry is not a landlord anymore. She has opened real estate businesses in Georgia and Florida, and did not respond to multiple attempts to talk with us for this story. We have found her mentioned favorably in various business trade articles, but her businesses seem to be relatively low-profile. Her profile on Zillow mentions property managing for landlords, but nothing about being a landlord.

In other words, Moutry appears to have left the landlord business. Renting slums in “the hood” may have been good for Moutry at one point, but does Desmond use this quote because it’s true, or because it fits his narrative? One thing is certain; it was not a sustainable landlording practice long-term. This means that the system, still in need of help, is not necessarily being hampered by people looking to make a quick buck off of dumpy rental houses. Unpaid taxes, foreclosures and leaving town are strange measures of success.

Was Desmond accurate in his book? Multiple sources believe so, lauding his scrupulous fact checking skills and attention to detail. In the epilogue of his book, Desmond goes into great detail about his fact-checking methods, which certainly seem exhaustive. There’s no reason to believe that anything he reported was false.

But is Desmond telling the whole story by allowing an incomplete narrative from 2008 to 2009 to stand in 2022? Not in this case. Allowing a half-truth to be part of the basis for eviction reform cannot serve either renters or landlords.

Full Accuracy Matters When It Comes to Evictions

As stated, we have no reason to believe that Desmond lied in his book, though there is some indication that he either did not investigate or opted to omit key details that would have formed a fuller narrative. Doing so may have made it difficult to continue to opine that landlords are making vast sums of money renting degenerate housing to low-income people hard on their luck.

Regardless, this has broader implications for Desmond’s work, both in his other sociological pursuits (he has received criticism for his alleged inaccuracies in his 1619 Project essay for The New York Times, and the project itself has faced criticism) as well as his work at Eviction Lab.

Desmond has long touted a voucher program as the way to help fix the housing crisis, and notes that different cities will require different approaches. However, a voucher program is an over-simplified solution to a complex problem. Desmond points out issues with the federal voucher program as it existed in 2008-09, in which landlords in less wealthy neighborhoods were overcharging for subsidized rentals based on the rental cap set forth for their city, and says that stabilizing rents is an important step toward funding a voucher program that would reach a broader population.

Unfortunately, rent control doesn’t work the way some people want to think it does, or should. Stabilizing rents may save money for a voucher program, and perhaps the way market rates are calculated should be re-examined, but rent stabilization can only really occur with rent control. There is a reason very few cities still have rent control, and it’s not because it effectively solved the housing crisis.

There’s also the claim that landlords would rather evict than bring a house up to code (and says in this video that landlords may see “extreme profit” off of renting in “very poor neighborhoods”). We aren’t going to say this is never the case, but how often is this truly happening? Desmond acknowledges that for some landlords, eviction “can be costly” but that for others, “it’s part of the business model.”

In a low-cost scenario, after missed rent, court fees and post-eviction costs, evictions can cost thousands. In Massachusetts, evicting rather than following the state sanitary code can also get you brought up on charges of retaliation. How bad do you have to let a home get before this becomes a beneficial business model?

In Massachusetts, for example, evictions under such circumstances are impossible. MGL Ch. 239, Section 8a, states that reporting code violations is a defense for a tenant withholding rent and protection against eviction:

“In any action under this chapter to recover possession of any premises rented or leased for dwelling purposes, brought pursuant to a notice to quit for nonpayment of rent, or where the tenancy has been terminated without fault of the tenant or occupant, the tenant or occupant shall be entitled to raise, by defense or counterclaim, any claim against the plaintiff relating to or arising out of such property, rental, tenancy, or occupancy for breach of warranty, for a breach of any material provision of the rental agreement, or for a violation of any other law.”

This is Massachusetts’ warranty of habitability, a concept that also exists in Wisconsin. There are always people who will attempt to work around the law, but it’s curious that greater education about tenant rights is not promoted more forcefully. Tenants should know that their landlord can’t simply throw them out for complaining about not keeping the place habitable.

Desmond has been criticized for coming to events and not paying attention to local issues, which brings us to our next concern. Eviction Lab does not engage with everyone involved with rental housing, even when looking at state data. It does not paint a complete picture of what states are doing to combat problems with eviction. How do we know that? We need to look no further than the pandemic and the ensuing eviction moratorium.

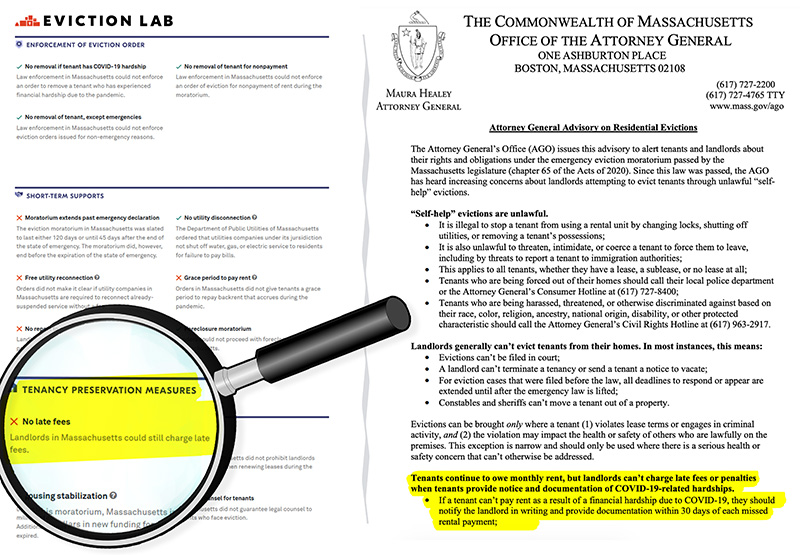

Cherry-picked data doesn’t help anyone’s cause. On the left, part of Eviction Lab’s Covid-19 scorecard for Massachusetts states that landlords were allowed to charge late fees. On the right, a notice from the Massachusetts attorney general from May 2020 specifically states that tenants who expressed Covid-19 related difficulties were not to be charged late fees. Image License: Eviction Lab and Mass.gov

A Scorecard That Also Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

Eviction Lab uses public information and purchased datasets to get its eviction numbers. During Covid-19, it issued each state a scorecard based on its eviction protection efforts.

The scorecard, which was updated regularly through June 2021, gave Massachusetts points for things such as banning notices to quit and eviction filings for non-payment. It dinged the state for not sealing evictions (though we maintain sealing eviction records also prevents tenants from vetting their landlords) and not offering a grace period for tenants to repay rent arrears. It only made passing mention of the state’s extensive rent relief efforts, which would have provided a more complete picture to those accessing the site. The scorecard also stated that “landlords in Massachusetts could still charge late fees,” but the attorney general expressly forbid this for tenants who had notified their landlord of Covid-related hardship.

It’s this sort of cherry-picking of data that will end up hampering housing relief. It allows people to focus on the problems they want to imagine exist, rather than examine the problems that are harder to accept, such as discriminatory administration of rental assistance.

We Agree: We Need Eviction Solutions

Nobody wants to go through an eviction. Landlords don’t want to take the time to go to court, wait up to 90 days to be able to get a new tenant, take the risk of never seeing their owed rent, etc. Tenants don’t want to be evicted because no one wants to lose their home. No one wants people to be homeless.

And we support housing voucher programs. In fact, we encourage our landlords to be enthusiastic about tenants who receive Section 8 or other assistance. It’s a fantastic way to not have to worry about whether you’ll get paid, because the government guarantees the rent payment, minus the tenant’s obligation. The one drawback is that rent may be delayed in the event of a government shutdown. (The government must still pay it after the shutdown; in the meantime, however, you’ve essentially given the federal government an interest-free loan.) In Massachusetts, it is illegal to deny tenants who receive public assistance; we wish more states would follow suit.

What we don’t agree with is shutting out landlord groups from the discussion. That pits housing providers against tenants, and the real issue is with affordable housing. Most of our landlords are mom and pop rental housing providers; they aren’t mega corporations with deep pockets, and leaving them out of the discussion basically guarantees a tepid response when rental solutions come up as ballot items.

We are grateful to activists like Desmond who push these ideas to the forefront and get people talking about them. But we need less storytelling and cherry picking and more hard conversations that include landlord voices. After all, landlords are half the equation in landlord-tenant issues, including eviction. It doesn’t make sense to pretend otherwise, or leave them out of the discussion.

We don’t agree with painting these problems with a broad brush, especially when Desmond, in “Evicted,” agrees that there are no simple answers. So why are we getting oversimplified data and oversimplified solutions? If we are to fix the housing crisis in America, we need a national overhaul of how we view housing. We need national, bipartisan support for voucher programs and anti-discrimination protections for those who use them, and a ban on curbside evictions. We need smaller, more attainable solutions in the meantime. We need to invite everyone to the table, listen with an open mind and not rely on sensationalism or easy-to-digest (but incomplete) solution soundbites to make our decisions. It’s only then that we can affect real change.