How to Create Affordable Housing in Massachusetts

Massachusetts and, more broadly, all US cities need affordable housing. Housing advocates typically mean “affordable” housing to be public or subsidized housing. When we talk about “affordable” at MassLandlords, we use the Oxford dictionary definition: “inexpensive; reasonably priced.”

In 1979, shops were permitted on Newbury St. But in the intervening 40 years, there has not been so much as a dormer added to the residential floors above. Boston.com Jen Ryan.

The goal of affordable housing is a spectrum of housing that permits all people to find housing of acceptable quality for a price that they consider inexpensive. Even people with extremely low income should be able to live with dignity and safety. People experiencing homelessness, renters, would-be homeowners, and actual homeowners all ought to be included in the discussion.

Renter advocates say there is a “Housing Crisis” and that emergency measures are needed to fix a broken market. In this article, we examine the market more broadly, focusing not just on renters. We offer several suggestions to create affordable housing in Massachusetts.

A Simplified History of Affordable Housing in Massachusetts

Housing was once affordable, but through our policies, we have caused it not to remain so.

It is informative to look at historical pictures of Massachusetts from the 17th century to the present day. What once was a meadowy Massachusetts Bay Colony is now a conurbation of almost three million people, with another four million spread out west. We have built a lot of buildings! But the pace of this development has slowed dramatically over the last century, and our language reflects this.

A Study of Words

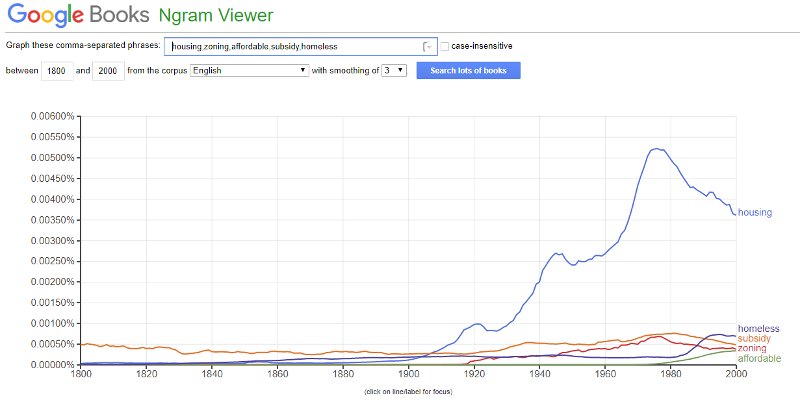

We can infer that the 19th century market was producing adequate supply for the inhabitants of the time by using the Google Books Ngram Viewer, which shows word frequency in books. People weren’t talking about housing the way we do now.

The word “homeless” first appeared around 1820. It remained at a very low frequency until around 1980, when it quickly increased in frequency by a factor of four.

The word “housing” likewise did not appear with any frequency until 1900, and then it increased in frequency by a factor of 30.

The word “zoning” appeared and skyrocketed to prominence in 1917, reaching a zenith in 1976.

The word “affordable” appeared first in 1970, and remains far and away the dominant and rising term today.

Is word frequency just a matter of changing language? In part, but words do reflect what we are concerned about. It became obvious to many in the early 19th century that some did not have a safe place to live. This concept crystalized in the “housing movement” of the late 19th and early 20th century, which then focused heavily on immigration and slums. The net effect of tearing down so-called slums was that housing became more expensive. Affordability and NIMBYism (first surging in use in 1986) is today the overriding concern.

Meanwhile consider the word “subsidy.” It has appeared consistently since 1800. Subsidies as a policy tool have been available for centuries, in other contexts, but have only been considered necessary in the housing context since the mid to late 20th century.

What has changed? The answer is zoning.

The Rise of Zoning

We know that affordable housing creation reached its zenith in the 1870’s, during the boom of the three-deckers. Three-deckers weren’t a public policy objective, they just happened as a result of a free market. Three-deckers were one solution to the problem of housing lots of people affordably. All totaled, at least tens of thousands of units of three-decker housing appeared over several decades. (No complete count has been made, but possibly over a hundred thousand units came online in Massachusetts.)

In 1912, the three-decker boom came to an end when Massachusetts passed the “Town Tenement Act.” This permitted cities and towns to ban any wood frame structure where cooking was to be performed above the second floor.

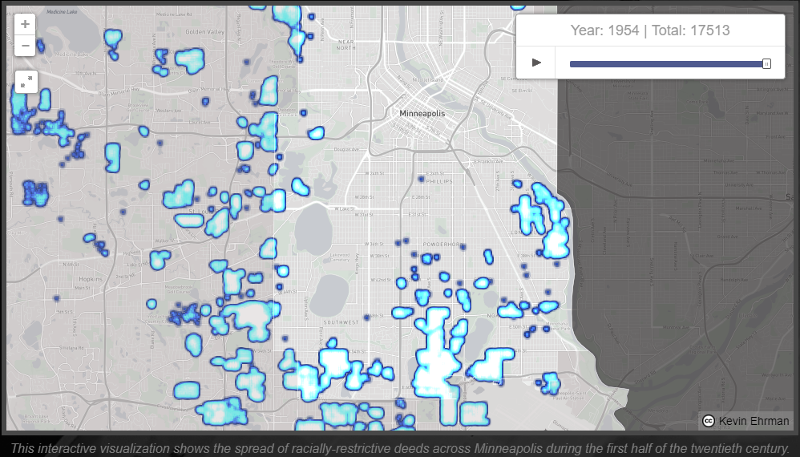

Two factors appear to have been decisive in the passage of the Town Tenement Act. First, three-deckers were objectively unpleasant by the standards of the time (no soundproofing, no air sealing, no insulation). They were also unacceptable by today’s safety standards (no fire blocking, no sprinklers, knob-and-tube wiring, etc.). Second, prominent Harvard graduates led by Prescott Farnsworth Hall opposed immigration, and viewed three-deckers as an attraction to undesirable neighbors. We know that this motivation was explicitly racist by looking at deeds in other cities elsewhere. Baltimore (December 1910) and Minneapolis (1911), for instance, specifically started restricting deeds to “Caucasian” or away from any “colored person or person of negro blood.”

This new racist and classist concept of “zoning” had a stifling effect on new construction and renovation. The Boston.com “Boston Then and Now” series shows this in photographs of the region over time. Organic change was rapid through much of Boston’s history, but then slowed through the first half of the 20th century. Change had ground to a halt by the 1970’s. Most of the pictures shown today are exactly the same neighborhoods and buildings since 50 years ago. In the photographs, we have to look at vehicles and clothing to see any difference.

Massachusetts “Snobs”

In 1969, rather than reverse course on zoning, we tried to patch the zoning problem by the passage of the anti-snob law, aka Chapter 40B. This freed large developers to override local zoning under certain conditions. Since then, developers have created large housing complexes, adding tens to hundreds of units at a time. But these developments have always appeared to stress schools and roads. Contrary to its purpose, the anti-snob law has actually increased popular resistance to density. Zoning now seems firmly entrenched among those who value private yards, large lots, and small classroom sizes. Few remember the racist origins of the policy.

Since zoning and Chapter 40B took hold, the population has continued to grow. Massachusetts has remained a world leader in education, healthcare, biotech, and other industries, attracting people from other states and other countries. But our housing supply has fallen far behind demand.

A Forecast and Systematic Housing Shortfall

In 2015, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council estimated that greater Boston needed an additional 300,000 to 400,000 units of housing by 2040 to meet forecast demand. This means we need to create approximately 1,500 units per month for Greater Boston alone.

According to the St. Louis Fed, Massachusetts has been averaging about 1,050 units per month state-wide since the Great Recession. This leaves us failing to meet demand, with increasing shortages, for the foreseeable future. To make matters worse, two economic factors mitigate the value of new construction.

A factor called “induced demand” is well studied in transportation: if we create new roads, people take more car trips than they otherwise would have. Traffic is not helped by the construction of new roads; in fact it is worsened. The phenomenon is described compellingly in The Power Broker by Robert Caro (1974). Induced demand in housing has not been studied, but remains an open question. If we create more housing, people may purchase more of it, in better quality, than they otherwise would have (vacation homes, more square footage, pieds-à-terre, etc.).

In housing, a more powerful phenomenon than “induced demand” will be “latent demand.” If we create new housing, it will enter the market at a luxury price point because everything is new. There are people everywhere looking to upgrade, to get into a better neighborhood, or to save on their housing expense, but they can’t because there are no options. Each new housing unit we create has to be absorbed by the latent demand before it can start to help those who just don’t have housing yet. Much new construction will shuffle existing residents around, rather than welcoming new renters and owners into the state.

In 1865, Tremont St in Boston was already a major urban neighborhood. Over a timeframe of 150 years, every building became taller. Boston.com Jen Ryan (see interactive comparisons at http://archive.boston.com/news/local/gallery/Boston_then_and_now )

Reducing the housing shortfall will no doubt require a multifaceted approach, as we describe.

Summary of Affordable Housing Recommendations

Here is a summary of editorial recommendations to increase affordable housing, in rough order of timeframe shortest to longest. Each topic could be an article in its own right. The first items can in principle be done easily, and the final, hardest item is to replace zoning with a new system that recognizes what zoning has to offer that’s good, but eliminates the racist, classist baggage. In order of easiest to hardest:

- Expand the safety net against homelessness.

- Grant the right to subdivide.

- Reduce the barriers to entering the trades.

- Shorten the eviction process.

- Eliminate artificial occupancy restrictions.

- Require beneficial owners be identified.

- Improve transportation to lower-cost areas.

- Replace zoning with a new framework.

The suggestions in this article have not all been voted on by the membership.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 1: Expand the Safety Net Against Homelessness

Over the next year, roughly 15,000 Massachusetts residents will experience homelessness. Such low-income and extremely low-income households represent the greatest gap between demand and supply of affordable housing. Congregate shelters help, but they are unfriendly, theft-exposed barracks in which no one would willingly spend a night. Emergency shelter is a band-aid, anyway. It does nothing to address the multitudinous and unique reasons each person lost their previous housing. We first need housing for all of these individuals and families, so we can then deal with whatever caused the homelessness in the first place.

A housing-first approach requires both public and private housing be available. Public housing has ten-year waitlists. We need more public housing. Private housing is not easy to get, either, where landlords screen tenants carefully. But in fact, we have enough private housing vacancies to shelter each of the 15,000 citizens experiencing homelessness tonight. Landlords don’t readily take the homeless into private housing because of the perception of risk. But the mechanisms to reduce risk are already here and working in coordination.

Consider that we already budget close to $200 million a year for shelters. We also fund permanent rental subsidies and a wide array of social service agencies who administer supportive services. The subsidy can ensure long-term economic viability in private housing. The supportive services can help with housing search, economic self-sufficiency, mental health, substance abuse, medical care, LGBTQIA+ issues, and the other factors that may drive one towards a state of homelessness.

This leaves housing barriers as the remaining issue. Massachusetts cities (Boston and Worcester) have started experimenting with landlord-tenant guarantee funds like those successfully implemented at scale in Washington, Oregon, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and California. These funds eliminate the perception of risk of a homeless rental application by offering large financial guarantees in the event of unpaid rent, property damage, or subsequent eviction. These guarantees are contingent on waving housing barriers, like bad credit. They are economically leveraged. For every dollar of guarantees made, only 17 cents are actually paid out.

A sustained, state-wide approach to homelessness ought to be able to use existing funding for shelter, subsidies, supportive services, and guarantees to reach functional zero homelessness.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 2: Grant the Right to Subdivide

Massachusetts needs a complex mix of housing units. One trend emerging is that tens of thousands of older units and homes are now too big for modern households, which emphasize single parents, single professionals, and smaller family sizes overall. Much of our housing is misallocated by few renters taking up large units that were built for the extended families of last century.

Small landlords can increase the housing supply dramatically, state-wide, for no state money, in an organic way that doesn’t stress schools or roads: subdivision of existing frames. Take a three bedroom and turn it into two studios. Take a single family with two floors and turn it into a duplex. Landlords cannot do this currently without zoning board approval. Typically zoning boards deny approval if there is not adequate parking, or if the lot is not zoned for multifamily housing. They make such denials even if the building is staying the same size, with the same setbacks, with no outward change whatsoever.

In communities with public transportation, including busses, there is no reason to block new housing for lack of parking. Such regulations put parking over people. In situations where the exterior structure doesn’t need to be expanded, there is literally no impact on neighbors, the neighborhood, or the exterior. Good investors pass on illegal two’s, three’s, and four’s because they don’t have the right to make those buildings legal.

A representative “Triple Decker” in Cambridge, MA. CC-SA Brian Corr.

The Boston Globe (January 31, 2015) has at least once published a landlord’s recommendation to create safe housing by subdivision of existing interiors. Tens of thousands of safe units will be created this way. These units will be more affordable than existing stock because they are smaller. Neighborhood look and feel can be preserved.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 3: Reduce the Barriers to Entering the Trades

Home improvement contractors, construction supervisors, and especially plumbers and electricians are essential to building and maintaining affordable housing. These trades require training before anyone can go off on their own. Consider plumbing as an example.

Plumbing is a demanding profession requiring long experience to excel. Leaks, mold, sewer contamination, gas explosion, and many other health problems will result from unskilled plumbing. But the difficulty depends on the job. Installing a SharkBite or replacing a faucet cartridge should not require 8,000 hours of training, yet in Massachusetts, it does. This is more than a bachelor’s and master’s of science (in most schools, only 6,000 hours). Many single-family homeowners are entirely unaware that it is not lawful for them to repair their own plumbing. This creates a vacuum of political will, but the need for reform is pressing.

Current rates for the trades including plumbing are around $100/hr. It is a good time to be in the trades. The result for creators of housing is we defer maintenance of all kinds. The Commonwealth needs more plumbers, electricians, and window installers, to name a few, and we need to offer lower level licenses for lower-risk repair-and-replace work. This will open up new opportunities for employment, at lower rates but with more consistent work. Reducing barriers to entry for the trades will greatly contribute to the creation and maintenance of affordable housing.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 4: Shorten the Eviction Process

It is important to look at eviction, as it is the final step on someone’s path to experiencing homelessness. Homelessness is best addressed via the safety net mechanisms described above. Although it may seem counterintuitive, a long eviction process is not net beneficial to housing stability, as it tends to reduce the accessibility of housing to all rental applicants, as we will explain.

Under current laws, especially MGL Ch. 239 Sections 4 and 8A, each Massachusetts eviction can be expected to take 90 days, unless a jury trial is demanded, in which case six months. Our review of thousands of court cases shows that each housing court, each month awards $500,000 of judgments for unpaid rent to local landlords. These costs are not paid out of thin air. They are paid by the other renters who didn’t get evicted. And they are paid by marginal applicants for whom the landlord is not going to take a chance, who experience long and frustrating housing searches. The average search time for someone exiting shelter is 10 months. Finding an apartment can be a yearlong effort or more.

By shortening the eviction process, coupled with a greatly enhanced safety net (see point one above), two things will happen. First, landlords will have lower operating expenses to be borne by their other residents. Second, landlords will need to screen renters less carefully, and therefore renters with housing barriers will get into housing more easily. Renters who are evicted will benefit from the improved accessibility of supportive services and a guarantee fund, described above. The safety net is best provided by the state, not by private landlords forced to endure costly and extended evictions.

The Google Books Ngram viewer shows that housing did not become a concern until roughly the same time as zoning came on the scene.

Two key eviction recommendations are as follows: Mandate rent escrow during habitability disputes, and lower the time a landlord has to store an evicted tenant’s belongings. These two changes might be expected to reduce eviction cost significantly without adversely impacting any tenant’s rights to due process.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 5: Eliminate Artificial Occupancy Restrictions

Massachusetts and its cities and towns have worked hard to deal with nuisance, and in some cases have restricted occupancy of dwelling units to related people. For instance, consider our lodging house statute, and the Worcester and Boston bans on “four or more” unrelated residents (which Boston has since extended to “five or more” if they are college students).

The SJC decided on May 15, 2013 that modernized apartments could be rented to four unrelated students, and that this did not constitute an illegal lodging house under state law (City of Worcester v. College Hill Properties, LLC, et al).

But cities like Worcester and Boston continue to enforce local ordinances prohibiting four or five unrelated occupants even if units meet square footage, egress, and other critical safety criteria. The cities do this primarily because they are afraid of college student density, which on occasion creates noise, parking nuisance, or other problems. Rather than regulate and fine the noise issue directly, they have banned all large roommate households.

In college towns (of which Massachusetts has many), eliminating the restriction on makeshift household sizes would greatly increase affordable housing as well as the number of residents each city can safely, lawfully house.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 6: Require Beneficial Owners be Identified

Privacy is a fundamental right in our society, but certain actions cannot be fully private if the public are to be protected. This is true in the fight against the funding of terrorism and organized crime.

As of May 2019, the BBC was reporting that over $5 billion had been laundered through purchase of real estate in British Columbia alone, which had the effect of raising prices in Vancouver by 5% city-wide. Globally and in Massachusetts, the effect of money laundering in real estate is not known, but likely comparable in scale, amounting to tens of thousands of affordable housing units in Massachusetts.

A terrorist or a money launderer can purchase a million-dollar rental property with no ID, over-declare their income to government, and walk around with their ill-gotten, fully laundered gains. Meanwhile everyone else who wanted to purchase that property with honest money has been priced out of the market.

Real estate remains a “wild west” compared to bank accounts. To open a bank account, the federal Bank Secrecy Act requires that individuals with a beneficial interest in that account be identified. If the account owner is a business entity, the owners of that entity must be identified, down to each owner with 25% or more interest in each entity. This has effectively eliminated terrorists and money launderers opening US bank accounts. But it has not stopped such organizations from purchasing real estate as replacement bank accounts.

The Mapping Prejudice project has created an overview of deeds that contain explicitly racist language in Minneapolis. Over 17,513 deeds were restricted to whites by 1954.

Real estate investors may not wish to have their names tied to their investments, on account of the current litigious environment. This is understandable. But the effect of money laundering on real estate prices and therefore on affordable housing likely runs into the billions in Massachusetts and must be dealt with for this and the obvious reasons.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 7: Improve Transportation

Like housing, public transportation is capital-intensive. So it creates additional work for us to solve transportation alongside housing. This is why this recommendation comes late in the list. But transportation is worth working on for housing’s sake.

As David Levinson discussed in his analysis of London rail, there is a positive feedback loop between mass transit and dispersion away from high priced urban centers. When surface rail and subway are brought into an urban core, the core becomes commercialized and ever more expensive, but residential zones move outward into less developed, more affordable regions accessed by extended rail service. This is precisely what metro Boston has not done: expanded rail access to permit residential access to the city from the 128 and 495 beltways.

Instead of viewing 128 as a commercial destination in its own right, we continue to direct all rail traffic right into Boston center, and there is no loop service of any kind. The Fitchburg commuter rail line is the only rail line to offer any service in the peak area of 128, and it’s only five stops cutting in the perpendicular direction. 128 should at this time have its own rail line from north shore to south. Commuter rail service on all lines should offer transfers to and from the loop trains. Bypass rails would facilitate “direct to Boston” express trains for the passengers who currently need to go all the way into Boston, permitting more local service around 128. Ticket prices should be increased to the point where fares cover capital costs, such that the money needed to build the expanded system can be borrowed and paid back with interest. The MBTA (and more broadly, MVRTA and PVTA) will be needed for affordable housing.

Until we can offer economically sustainable transit to a wider area, we will continue to see concentrations and high residential prices in the limited areas served by rail and bus.

Affordable Housing Recommendation 8: Replace Zoning with a New Framework

As we have seen, our regulatory framework has a significant effect on housing prices, and zoning is not the least important factor. Zoning may in fact be the single most important factor.

By artificially constraining supply, zoning drives up prices from the “affordable housing” setpoint. By keeping density low, zoning renders infeasible any expansion of public transit. And by keeping renters and support networks out of huge swaths of Massachusetts, zoning concentrates and aggregates issues of eviction and homelessness, and excludes rentals and the trades from many areas.

To the extent that zoning serves a legitimate purpose, it can be recast as a set of regulations on externalities. Consider a perfect single family, the picture of an ideal neighborhood. To the extent that it doesn’t impact its neighbors in any way, that single family is free to exist. Now consider a sawmill next door. Zoning currently prohibits this. Or we could list out all the undesirable things sawmills do to neighbors and prohibit any property from doing any of those things. If a sawmill could operate without noise, heavy trucks, flood lighting, clouds of sawdust, an ugly building, a tall building that blocks out the sun, or any of the other perceived deficiencies of sawmills, why shouldn’t it be allowed to operate next to a single family? This same logic applies easily to rentals, which are much less onerous than any sawmill.

Think of college housing, which can result in noisy parties and beer bottles thrown across property lines. Think about homeless shelters, which can result in loitering or solicitations. Think about rooming houses, which can result in noise and high turnover of neighbors. Think about any type of person who is not like you. Instead of banning all these different people, it is easy to imagine instead enforcing bans on noise, trash, blocking sidewalks, whatever it may be. The whole zoning system can be replaced with one that actually serves all residents of the community, provided we all leave one another to go about our business. It is not necessary to ban numbers, classes, colors, or incomes of others. We are now sophisticated enough to describe and ban only what is having a demonstrable bad effect on another.

(Incidentally, a system of externality regulation would be ideally suited to address other problems not currently addressable, for instance, greenhouse gas emissions. If ever there were a clearer example of a negative externality wanting regulation, climate change is it.)

Zoning does nothing to curb negative externalities, and when you consider its racist and classist origins, it’s clear that zoning as written stands in the way of affordable housing.

Affordable Housing Conclusion

It will be noted that nothing in this discussion required a great deal of landlord-tenant regulation. Much of the “housing crisis” conversation is focused too narrowly on the rental market. It is important to remember that in Massachusetts, by far the largest use of our housing and land is those areas we zone “residential single family.” Landlord-tenant policy pales in comparison to this bigger picture.

Did we miss anything? Email us your affordable housing suggestions at hello@masslandlords.net. These proposals will be voted on by the membership as they gain traction and come up for vote at the state level.

Members can vote on policy proposals online anytime.