The Complete Guide to the MassLandlords vs. EOHLC Loss and How it Hurt Renters

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

With its dismissal in February 2024 of our 2 and a half-year public records lawsuit against the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC), the Superior Judicial Court (SJC) took us a step backward as one of the least transparently governed states in the nation.

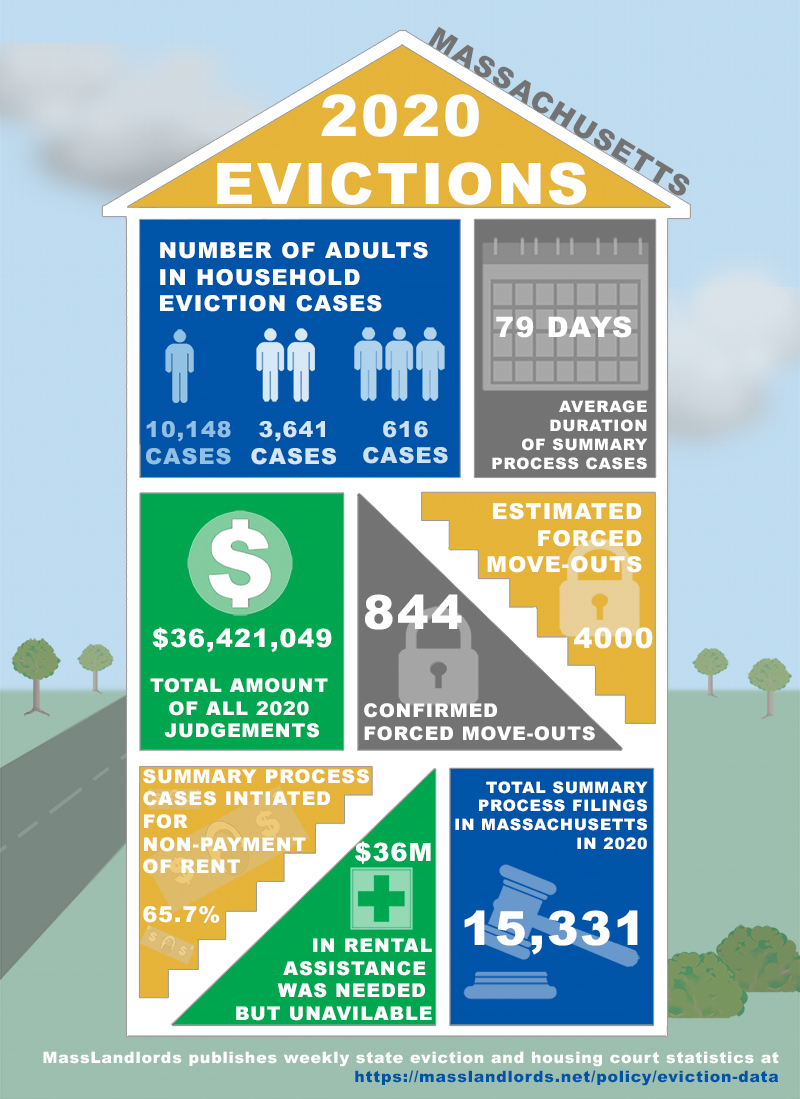

As shown in this infographic, $36 million was needed but unavailable in 2020 for renters to avoid evictions. Yet, more than 65% of summary process cases were for nonpayment. Why were so many renters, who were unable to pay their rent, turned away for rental assistance during the pandemic year? Image: cc by-sa 4.0 Jennifer Rau MassLandlords.

In this article, we will do what the media would not: examine and question how it came to be that Massachusetts spent $800 million with zero public oversight, and blocked our attempts to shine light on it.

On Feb. 15, 2024, the SJC rejected an application for further appellate review of the MassLandlords lawsuit to gain access to thousands of addresses (but not applicants’ names) on applications that were denied rental assistance during the Covid pandemic. More than half the applications for pandemic rental assistance were denied despite ample federal funding. Almost all of those were “timed out” for various reasons. Worst of all, 47,000 applications were printed and set aside in boxes, lost to supervision. As a result of this mismanagement by EOHLC and regional administering agencies under its supervision, tens of thousands of families and individual renters were denied rental assistance when they needed it. Many evictions surely resulted from this oversight.

We noticed early during pandemic rental assistance that application time-outs were inordinately high, and wondered why. In 2021, we made severalpublic information requests to EOHLC (which was then called the Department of Housing and Community Development). They were all denied for procedural, unrelated reasons.

In December 2021, we filed our lawsuit. Initially, the EOHLC attempted several defenses. The department first stressed that the records we sought were not available. Retrieving them – including those 47,000 boxed and unsupervised – would require hiring 39 full-time employees, plus $200,000 for printing and mailing, it claimed. (It sounds like a lot of money, but it still would have been a drop in the bucket of the billion dollars the state received to cover all costs, including administrative; and well-spent considering what was at stake.)

The defense also argued that our access to the applications would be a breach of privacy for people living at the addresses we sought; though, as we emphasized, we were not seeking people’s names, only addresses. Still, the EOHLC (DHCD) argument was logically inconsistent: If the right to privacy applies to a recipient of rental assistance, then why does someone who did not get rental assistance also have a right to privacy? We were seeking addresses of both.

After a motion to dismiss the suit was filed by EOHLC and granted, we filed in superior court. Our complaint was dismissed in June 2022 by Superior Court Justice Jackie Cowin. Read details about the dismissal. We appealed the case to the Court of Appeals, and were denied appeal after long delays on the part of the court. We immediately filed an application in late 2023 for further appellate review, called a FAR, in the Superior Judicial Court, ending with the February rejection.

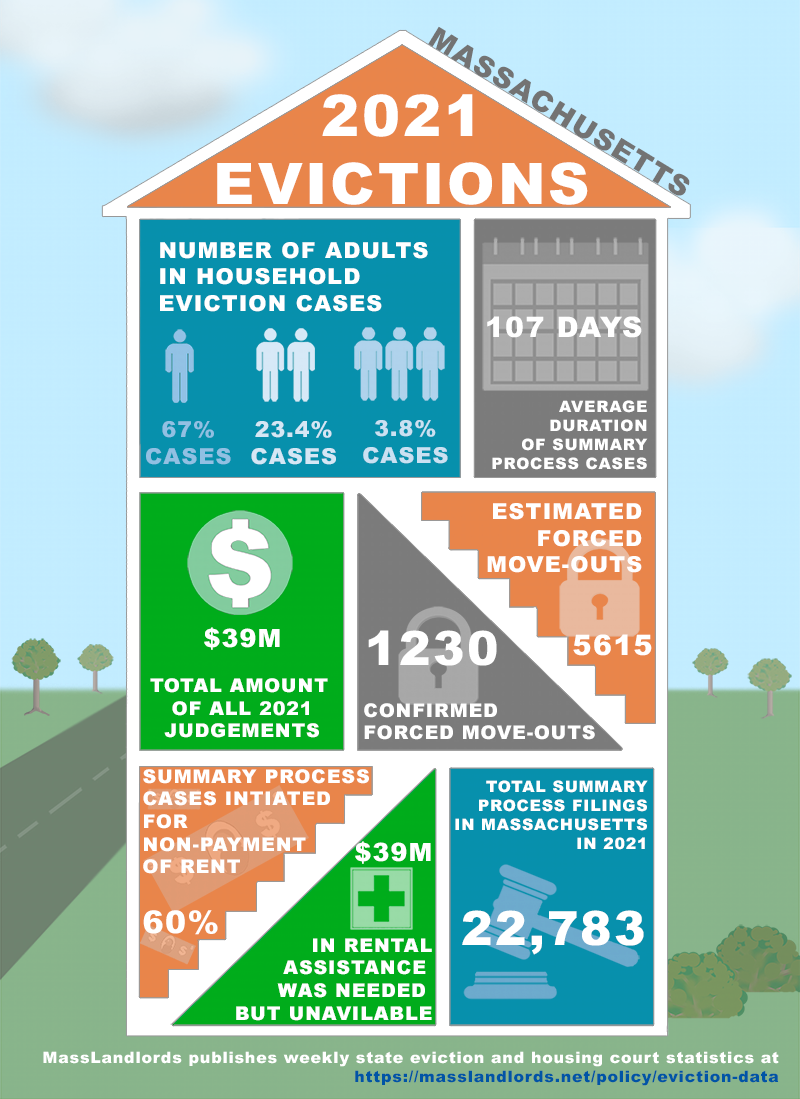

By 2021, as pandemic RAFT was kicking in, the situation had not changed much, with 60% of summary process cases for nonpayment and $39 million needed but not made available for rental assistance. We wonder: When evictions were paused during the pandemic pending RAFT, how could so many people have been evicted? How could the courts find that they owed and could not pay, yet the state decide they were ineligible to receive rental assistance? Image: cc by-sa 4.0 Jennifer Rau MassLandlords.

Public Right to Know

We pursued our complaint all the way to the SJC because we were convinced that the state’s obstruction could not be legally sustained.

Public records law states that the starting assumption is that everything in the executive is a public record. It grants exemptions for personally identifiable information. Addresses are not private records. Addresses, in many contexts, are public: deeds, tax records, evictions, when you show a bartender your license. There are only three public information exemptions for addresses, none of which were met in the EOHLC’s claim.

By comparing the addresses of rejected rental assistance applications against publicly accessible addresses of tenants involved in eviction cases, we hoped to illustrate a correlation between denials and protected classes. This would prove what we already know: that state applications were discriminatory.

Why should the applications for rental assistance have been printed in English with only unreliable Google translations for other common languages? This discriminated on the basis of national origin. Why should the applications have required lengthy essays? This discriminated on the basis of disability, particularly people sick with Covid who couldn’t write. Why should the applications have required listing all children? This discriminated on the basis of family status. Lastly, because of intersectionality, the applications ultimately discriminated on the basis of race.

Our argument emphasized the public’s right to know what happened within state agencies that resulted in tens of thousands of rental assistance applications being timed out or rejected. More importantly, we sought to force potential accountability and assist more renters in remaining in their homes going forward. If, as we suspect, rental assistance denials were incongruently impacting people of color, immigrants and others, whether inadvertent or not, we argued, the public should know about it.

Our public records litigation was to get access to information that would have enabled us to make that determination.

Massachusetts Public Records Law?

The public’s right to know what is happening behind the scenes of government is at the heart of the public records law. Some version of laws requiring the disclosure of public records has been in place in Massachusetts for more than 150 years.

The Massachusetts public records law is a version of the federal Freedom of Information Act, which was enacted in 1966. However, Massachusetts is unique among U.S. states in the extent of its exemptions from the law. In fact, Massachusetts stands alone as the only state in which the legislature, governor’s office and judiciary enjoy exemptions from having to disclose public records.

The state’s current public records law was written in 2017 and signed by Governor Charlie Baker amid promises for more government transparency. But was that lip service? The governor claimed exemption from the law, too, when he was sued for public information by the Boston Globe in 2017. His exemption claim was upheld by then-Attorney General Maura Healey, who, as governor, has also exempted herself from filling public records requests.

The new law removed some obstacles to gaining access to public records, such as exorbitant fees. But it did nothing to clear away some of the exemptions. Municipalities and state offices have a long list of reasons to exempt themselves from providing public records, and redacting them when they do comply with requests.

The new law also did nothing to ease the claim of privacy rights that government officials often overuse to deny requests for public information.

Further, ignored public records requests are rampant in Massachusetts, with little oversight or enforcement. Thousands of public records requests are ignored and unfilled every year by public offices, most notably the MBTA and the State Police.

Combined, the exemptions crafted in Massachusetts’ public records law and the law’s weak enforcement make ours one of the least transparent states in the nation. Such public information opacity obviously lends itself to corruption, cronyism and legal laxity, as we are witnessing.

Now, the state legislature is proposing yet another attempt to shield government process in the form of an eviction sealing bill.

“Failure to State a Claim”

The SJC’s reason for its denial for appeal was “failure to state a claim.” The full legal phrase is “failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.”

Dismissing a case based on “failure to state a claim” does not refute the complaint brought by the plaintiff or absolve the defendant. It only says that the court refuses to carry the case forward based on its perceived impossibility. “Failure to state a claim” is not a win or loss for either party, though it effectively benefits the defendant in this case by waiving its responsibility to comply. But importantly, the SJC’s dismissal does not declare the state’s innocence, or adjudicate that the state has done nothing wrong.

This spurious dismissal by the SJC leaves us perplexed and frustrated. We couldn’t have made our claim for cure any clearer: We demanded the release of records that would help us compile statistical data to determine trends in application denials and time outs.

The release of the records we sued for could help us create a correlative pattern that might have corroborated our suspicions of discrimination. Armed with that information, we and state agencies could have addressed the problem so it would not continue or happen again.

Public records lawsuits frequently seek only to retrieve information, as opposed to monetary damages from, or punishment for, the defendants. Such lawsuits, by their nature, are requesting non-material recompense, i.e., the release of public information. Therefore, the “claim for relief” would be the stated request to release public records that would have assisted us in determining fault.

Two Steps Backward

With its dismissal of our FAR application, the SJC did two destructive things:

- It created an example for future obfuscators to point to in denying public records requests.

- By doing so, the court increased the barriers for obtaining public records in a state that already is one of the most opaque in terms of government transparency and accountability.

Public records law is an essential component of democracy. Academic researchers, journalists, trade associations and individuals have the right to review details about how their government works, makes policy and appoints people to positions of power.

Without that right, and the cooperation of government institutions to be transparent in their workings, democracy is threatened. Government by the people is potentially replaced by government by a small group of individuals behind closed doors.

Questions Remain

After 2 and a half years, multiple legal briefs, four affidavits, several courts and a community of judges, we are still left with our original question. Why were tens of thousands of applications for rental assistance timed out or rejected by authorizing agencies with no substantive explanation given by EOHLC?

Will we ever know?

Public records law is broken in Massachusetts. With its meek denial of our request for further appellate review, the SJC further strengthened the state’s ability to operate without accountability, out of public view, free to mismanage without scrutiny or oversight.

While the public records law is no longer an option for us, we are not giving up our fight for state government accountability. We have filed a bill in the legislature that would fix the gap in our public records law regarding rental assistance. Our bill, “An Act Relative to Residential Assistance to Families in Transition (RAFT),” includes the following clause in section 2: “In order to ensure the just, efficient and discrimination-free administration of housing services, a document made by the Department of Housing and Community Development or its agent, whether a Regional Administering Agency or other person or entity, pertaining to rental assistance in any form described under Chapter 23B or Chapter 151B Section 4, shall be considered a public record under this chapter to the extent it identifies the lessor, owner, manager or other recipient of funds, the precise address at which housing services were rendered, and the amount and dates of such assistance, provided however that the names of renters, tenants, subtenants, and other occupants of the premises at time of such assistance shall not be public records.”

The bill has so far not gained traction in the legislature.

Also, the option remains for us to sue EOHLC directly for discrimination in rental assistance allotments. Through discovery of that process, we could obtain the addresses we originally sought and still make our comparison.

We will continue fighting for transparency in government and equity in rental assistance. Our democracy depends on it. It’s also essential for our mission of creating a better rental housing environment for both tenants and landlords.