Pending Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Bill is Essential to Landlords’ Property Protection

| . Posted in News - 3 Comments

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

Civil asset forfeiture is a controversial policy that empowers law enforcement officers and representatives to seize personal property – cash, cars, homes, boats, jewelry, clothing – from anyone, even if the property owner is not suspected to be involved in criminal activity.

Cash, cars, homes, boats – civil asset forfeiture laws allow law enforcement officers to take any of these personal items (as well as clothing, jewelry and others) from individuals, including landlords, if they are suspected of being involved in a crime. Images: cc by-sa Wikimedia commons

If your property, such as a rental unit, is used by someone else to commit a crime, you, as the owner, may be forced to forfeit it, or hand it over to police.

Landlords’ property is vulnerable under the law. Imagine you have a tenant who is selling illegal drugs out of their apartment without your knowledge. This gets on the radar screen of the local police department, which builds an ongoing investigation with your property as the focus. Under civil asset forfeiture law, the police may eventually move to seize your property as part of their investigation.

A Law Due for Reform

Civil asset forfeiture is a law in need of reform, especially in Massachusetts.

Thanks to proposed legislation written and submitted by MassLandlords Legislative Affairs Counsel Peter Vickery, that reform might be in the offing.

Vickery drafted and submitted a proposed legislation with the 192nd legislature that would improve the state’s outdated civil asset forfeiture policy. His draft was filed by Representative David LeBoeuf. The bill, S.2988, An Act Relative to Forfeiture Reform, was passed by the state Senate on June 30, 2022, by a 31-9 vote, and awaits legislative action in the House.

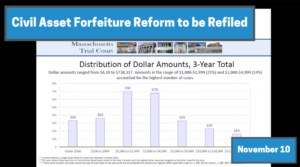

(Because the 192nd session has formally ended, the civil asset forfeiture legislation will be resubmitted for the 193rd session.)

Nonetheless, the progress of S.2988 marks a successful first for MassLandlords in bringing legislation important to landlords to the doorstep of enactment. S.2988, which was sponsored by Senate Majority Leader Cynthia Creem, is an amalgam of several bills related to civil asset forfeiture, but contains the core ideas originally proposed in Vickery’s draft. We called on you to support the bill – thank you for your actions that made a difference.

Is Civil Asset Forfeiture Necessary?

Civil asset forfeiture is a complicated and controversial issue. Importantly, no crime need be committed or charged in order for property seizure to take place. The suspicion of a crime is all that is necessary for police to take a private citizen’s personal property under civil asset forfeiture policy in Massachusetts.

Most states and the federal government have civil asset forfeiture laws in place. A few states have rescinded these laws and legislation has been introduced in others to change or remove civil asset forfeiture.

Our nearest neighbors, Connecticut, New Hampshire and Vermont, all require a criminal conviction for property seizure. Maine abolished civil forfeiture altogether in 2021, joining Nebraska, New Mexico and North Carolina as the only states without civil forfeiture laws.

Only in Massachusetts

Thresholds of proving citizens’ guilt and association with crimes vary from state to state. Most states require a “preponderance of the evidence” indicating that property being seized was more likely than not associated with criminal activity. However, Massachusetts is the sole state still retaining a lower threshold of suspicion, requiring only that there be “probable cause” that seized property was involved in a crime.

The phrasing used to establish the burden of proof draws an important distinction and shifts the legal burden between the private citizen and the law enforcement officer. The current “probable cause” threshold in Massachusetts law requires no evidence of a crime – rather, only a reasonable suspicion, supposedly based on circumstances, to warrant property seizure. The burden is on the defendant to prove no wrongdoing in order to reclaim their property or avoid its seizure.

The proposed “preponderance of the evidence” threshold would place the burden on the plaintiff (law enforcement personnel in this case) to show that any available evidence more likely than not points to criminal activity or involvement.

The new legislation would change the Massachusetts civil asset forfeiture threshold back to “preponderance of the evidence,” in accord with other states. Massachusetts’ law originally held that language when first adopted in 1971. The law’s language was changed in 1989, easing the burden of proof for law enforcement.

Massachusetts also holds the distinction of having no deadline in place for district attorneys to notify individuals that they have their property. In some cases, DAs have held onto cash and property for several years before notifying owners of their right to file for its return. The new law would establish a reasonable timeline for notifying people regarding the seizure of their property.

Potential for Corruption

Few law-abiding citizens would argue with the right of law enforcement to take – i.e., forfeit – a drug dealer’s cash or car, for example, when they have been obtained through unlawful means. This is a common occurrence of civil asset forfeiture. Law enforcement groups insist that civil forfeiture is essential to their ability to disrupt organized drug trafficking and other unlawful behavior.

But the process in the laws can be complicated. One complication is what happens to property once it’s forfeited to law enforcement. In Massachusetts, seized property is split evenly between the county district attorney’s office and the local or state police department that seized the property. Non-cash assets such as cars and property can be sold at auction for cash after a certain time period has passed without a claim on the property.

Of course, such a system is potentially self-serving with a conflict of interest built in. It creates an incentive to suspect criminal activity even when no crime is being committed. This happens frequently.

One high-profile case involved Ameal Woods, who was driving a rental car near Houston, Texas, in 2019. A police officer pulled him over, allegedly for driving too close to a vehicle. Woods and his wife, Jordan Davis, were carrying $43,200 in small bills – their life’s savings – which they said they planned to possibly use to buy a tractor-trailer for Woods’ business. With no evidence of a crime, the police officer let the couple go without a ticket, though he seized their cash based solely on the suspicion that they were up to no good – i.e., carrying a lot of cash. The couple filed a class-action lawsuit to retrieve their cash. The case is still pending.

The pending Massachusetts legislation would partly remove that incentive by putting any seized assets in a general fund instead of police or district attorney coffers. The bill would also establish a database, under the Executive Office for Administration and Finance, to track details of all forfeitures for the first time.

Right to Counsel

Other important changes in the reform bill would include providing the right to legal counsel for indigent individuals whose property has been seized.

As currently structured, Massachusetts’ civil asset forfeiture law places the burden of proof on the citizen to retrieve their own seized property. In hundreds of cases – 25% between 2017 and 2019 – the amount of money seized by law enforcement was less than $2,000. No wonder that in some 80% of those cases no claim was made for the money – the legal fees would surpass the amount retrieved.

The recently passed Senate bill would establish a fund, using money procured from the sales of assets and cash in criminal forfeiture cases, to pay for defendants’ legal defense.

The reform bill would also disallow district attorneys from pursuing civil forfeiture cases on amounts less than $250.

A Massachusetts Case

Massachusetts landlords are vulnerable to the state’s civil asset forfeiture laws. Especially for landlords who do not live near their rentals and can’t regularly monitor them, the potential for illegal activity to ensnare landlords is baked into the law.

Consider the case of Russ Caswell, owner of Motel Caswell in Tewksbury. Caswell was a hotelier, not a landlord, but one can easily transpose his situation to a landlord-tenant scenario.

Caswell took over the hotel from his father in the 1980s and ran it for years. That is, until the federal Drug Enforcement Agency teamed with the Tewksbury Police Department several years ago to seize the property. The seizure was based on some guests selling drugs at the property (30 times over 17 years), which Caswell argues he was unaware of.

The Caswells, who stated they had always cooperated with law enforcement, enlisted the nonprofit Institute for Justice and eventually succeeded in getting their hotel back.

In most civil asset forfeiture cases, cash and property is not returned to the owners even when the charge of a crime was never levied.

Asset Forfeiture Vulnerability for Landlords

Imagine a similar scenario to Caswell’s, in which your rental property becomes the subject of a drug investigation. Maybe you rented to a tenant four or five years ago who dabbled in selling drugs. When you found out about the illegal activity, you took action to evict the problem tenant.

Meanwhile, the local police department had been building a file on that tenant, with details about his residence, including you as the property owner. Now they inform you, as part of their ongoing investigation, that they plan to seize your rental property due to its involvement in illegal drug activity.

A MassLandlords member from Cambridge, who asked not to be identified, was ensnared in just such a scenario. Importantly, his situation took place nearly 30 years ago, and was part of a federal government investigation, not state. Federal civil asset forfeiture law has since been reformed so his situation may no longer take place at that level. In Massachusetts, it’s still plausible.

In 1992, the individual had fired a property manager who was tending his rentals in another Massachusetts city. But that property manager was under federal investigation for drug offenses while managing the member’s properties, and he alleged to federal authorities that he owned the member’s property. That allegation, though it was plainly false, was enough to empower federal authorities to issue the member an ultimatum: sell his rentals or they will be seized. He sold at a loss amid a depressed market in order to avoid seizure.

“It was morally reprehensible,” the member recently told MassLandlords, reflecting on his situation in 1992. He agrees that it’s high time Massachusetts civil asset forfeiture policy is reformed, at least to avoid such miscarriages of justice as he endured at the federal level. “It’s just wrong.”

A Distorted Law

Massachusetts’ civil asset forfeiture law was enacted in 1971 as a tool for law enforcement to target the assets of organized drug criminals. It has since deteriorated into a law that disproportionately targets poor and indigent people, and petty criminals. It has also become a lucrative, if sometimes questionable, source of revenue for police departments.

The law in its current form also endangers landlords, who are vulnerable to the low burden of proof when tenants potentially commit crimes on their property.

The reforms in S.2988 would take nothing away from law enforcement. Police officers would still retain the power to seize assets obtained through criminal activity. But importantly, the proposed reforms would protect landlords’ and citizens’ property from unjust seizure.

You can still assist in this important reform by contacting your legislators and urging them to support this bill.