Martin Green vs. the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination: A Cautionary Tale for Landlords

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

By Kimberly Rau, MassLandlords, Inc.

One Massachusetts property manager is fighting what he considers a losing battle against the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) after one of his tenants made a discrimination complaint against him.

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination has made headlines for how long it takes to settle cases. Interim Executive Director Michael Memmolo says they’re trying hard to work through the backlog. (Image License: CC by SA 4.0 MassLandlords, Inc.)

Back in 2017, Marty Green butted heads with a tenant, Nicole Evangelista, over her boyfriend’s dog. Evangelista reported him to the MCAD. Years later, Green is still working to call out what he considers injustices perpetrated by the anti-discrimination group. He is already banking on losing his appeal with the MCAD.

After learning about the case, we spoke at length with Green, as well as two representatives from the MCAD. What follows should serve as a cautionary tale for all landlords. A discrimination charge could take years to settle and may set you back thousands of dollars.

Recourse for Protected Classes in Massachusetts

Massachusetts has multiple protected classes. It is illegal to discriminate against someone on the basis of race, religion, national origin, family status, ancestry, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, genetic information, military status, age, receiving public assistance and disability. The law also prohibits retaliation against someone who claims they have been discriminated against.

If someone experiences discrimination, they can pursue their case in court. They can also appeal to the MCAD and have their case heard by a hearing officer who has the power to make a determination on the case and award damages.

In theory, this setup takes some pressure off the courts. Housing is a basic human right, and if people are being blocked from accessing it due to discrimination, there should be avenues available to them to get justice, even if they cannot afford a lawyer. However, Green brought up several concerns with the way the MCAD operates. On the surface, these concerns seem to throw up roadblocks to those who are most vulnerable.

Evangelista, Fortin & the MCAD vs. Marty Green

In 2017, Green, a property manager, reached out to one of his tenants, Nicole Evangelista. The issue concerned her boyfriend, Joshua Fortin, and his American Staffordshire terrier, Sam. Fortin was not on the lease, but both he and Sam were staying in the apartment. The lease said no animals were allowed, and some neighbors had allegedly complained about the dog. Green had already warned Evangelista once about Sam, and now he wanted Evangelista out.

Over a series of emails, Evangelista countered that Sam was a service dog who alerted Fortin, a diabetic, to drops in his blood sugar. Green said he wasn’t going to argue about the matter anymore. Following that, Evangelista filed a complaint with the MCAD.

What happened after, in Green’s eyes, was a breach of justice.

“I believe in process,” Green told MassLandlords. “If they had used good process, even if I didn’t like the decision, I’d have to accept it. But they didn’t.”

Green’s Issues with the MCAD’s Procedures

Among other things, Green alleges that the MCAD did not contact all of the witnesses Green supplied. This included the woman who made the original complaint about Sam’s behavior. When we asked the MCAD about this, Wendy Cassidy, counsel supervisor for the MCAD, would not comment on a case that is still in appeal. But she did note that in any case, both the complainant and respondent are able to subpoena anyone they’d like for the hearing, and this tenant was not subpoenaed by either side.

Green also stated that the MCAD bolstered its claims by referencing conversations between Green and Evangelista’s mother that he says never happened.

To try and prove that Sam was not a service dog, Green hired and paid for Sher Ann Rossi, a dog trainer whose business is training service dogs, including diabetic support dogs. Rossi determined that Sam, who had never been trained to detect blood sugar levels, was likely not a service animal. Any correlation between Sam’s behavior and Fortin’s blood sugar levels was likely a coincidence. Rossi did suggest that Sam might be an emotional support dog.

Green said that after that testimony, the hearing officer determined that Sam was an emotional support dog because Fortin believed that Sam was providing a service, and the placebo effect of this belief gave Fortin emotional comfort. However, Green argued, determining whether an animal is an emotional support animal is not within the scope of an MCAD hearing officer.

Green did not settle with the MCAD, or agree to pay for mediation. Instead, he opted to let the hearing play out. He said other landlords may choose to do otherwise because they know they won’t win against the MCAD.

“I could have paid [the MCAD] off years ago, but I was not going to let anyone tell me that I had discriminated against somebody,” said Green. “But other landlords, they just go, ‘wait a minute, this is a stacked deck, I’m just going to pay them off.’”

Green lost the hearing. The hearing officer determined that he had acted in a discriminatory fashion about Sam, had not engaged in dialogue with the tenants and had retaliated against them by sending them notices to quit after they had complained to the MCAD. Green refutes the allegation. The notices to quit were for nonpayment of rent, he states, and other tenants had also received such notices.

As a result, Green was ordered to pay thousands in damages. Fortin was awarded $10,000 in damages. Evangelista, $20,000. Green was further ordered to pay $7,500 in civil penalties; his LLC was ordered to pay an additional $5,000 in civil penalties. The landlord was also issued a civil penalty of $5,000. These penalties go to the Commonwealth, not Fortin or Evangelista. This adds up to $47,500, most of which Green is liable for, unless he wins his appeal. This does not include legal fees.

Green’s appeal largely centers on the idea that if a doctor or other appropriate professional has not determined that Sam (who has since passed away) was an emotional support animal, then Sam was a pet, and nothing more. If that’s true, Green believes his actions surrounding the dog cannot be discriminatory. Pets are not protected under the Fair Housing Act. And the MCAD is not one of the listed professionals able to issue letters of support for emotional support animals.

Green expects to lose. Once that happens, he plans to take the case to Superior Court.

“The hope is an objective judge will start asking some thoughtful questions about due process and MCAD’s objectivity in their decision making,” Green said.

Discrimination, a Breach of Justice, Both, or Neither?

To understand Green’s concerns, we read both the original determination from the hearing officer, as well as Green’s appeal and some supporting documents he sent us. But we aren’t lawyers, judges or hearing officers, and weren’t able to make a determination about the case. If Sam was a service or support animal, she should have been permitted under the laws surrounding reasonable accommodations.

To get to the root of Green’s concerns, we had to research the commission’s origins, and learn about how it operates. This meant reading financial statements that were part of the public record, newspaper articles about certain cases and the MCAD’s bylaws. The more we read, the more questions we had, so we contacted the MCAD.

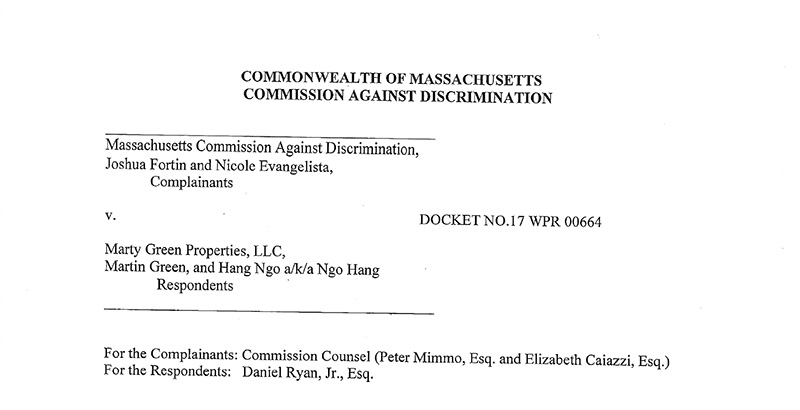

The hearing officer for the MCAD determined that Marty Green discriminated against his tenants. Green counters that the MCAD did not examine all the evidence and overstepped its bounds issuing the judgments it did. (Image license: Public Domain)

How the MCAD is Structured

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination was founded in 1944, under the name the Fair Employment Practices Commission. It became known as the MCAD in 1950, when the purview of the commission expanded to include discrimination in housing and other public accommodations. Its scope has expanded over the decades as more protected classes have been added in Massachusetts and on the federal level.

Today, the structure of the MCAD consists of three commissioners, including the chair of the commission. These individuals are appointed by the governor. This will be a quick overview of how discrimination complaints are handled through the MCAD; the actual process is much more nuanced and can be found by reading the MCAD’s full rules of procedure.

When a complaint is brought to the MCAD, the chairperson will select one of these commissioners to investigate the claim. The commissioner may also have a designee who investigates on their behalf. This investigating commissioner looks into the case and, after investigating, writes up a disposition containing the investigator’s determination. This disposition indicates finding of probable cause.

At any point in the process, the parties involved may agree to go into mediation to attempt to find a solution for the reported issue. Complaints may also be amended up until a certain point in the process. The person making the report is called the complainant; the person or entity who is alleged to have acted in a discriminatory way is called the respondent.

If the complaint reaches the hearing stage, the chairperson will appoint one of the three commissioners to be that case’s hearing commissioner. There is a preliminary hearing, and a public hearing. Both parties may have legal representation. The MCAD has attorneys it utilizes if the complainant is not able to afford one on their own. Though it is not a judicial body, the MCAD was granted jurisdiction by the legislature to make determinations on discrimination cases and award damages and legal fees.

MCAD decisions may be appealed to the full commission. Following that, the case may be brought to Superior Court for further examination if necessary.

The MCAD Responds to Our Questions

Government transparency in Massachusetts can be a tricky thing. Back in 2015, the Center for Public Integrity gave the Commonwealth a D+ for overall integrity. When the grade was broken down into categories, Massachusetts got an F for judicial accountability.

Granted, that study is nearly eight years old. However, given that we are currently suing both the Department of Housing and Community Development and the city of Boston over transparency issues, it would be hard to say a whole lot has improved. When we sent over an inquiry email to the MCAD for this story, we did not expect much in the way of comment.

We were wrong. The interim executive director, Michael Memmolo, responded to our query within a day. He had the group’s senior counsel supervisor Wendy Cassidy speak with us, then spoke with us as well. We appreciate the MCAD’s willingness to go on the record with us so freely.

The charge: The MCAD does not conduct thorough interviews, and evidence rules are less strict

By design, MCAD will hear evidence traditionally not allowed in court. This can be appealing to complainants that may not have much evidence of misconduct. For instance, a one-on-one verbal conversation between a landlord and tenant that hasn’t been recorded (Massachusetts requires both parties to consent to such a thing) is difficult to prove. The MCAD will consider such evidence.

In our example case, investigators said Green had asked his tenant’s mother to prove that Sam was not a service dog or help him get the dog out of the apartment. Green denies any such conversation took place and questioned how the MCAD expected him to prove it hadn’t.

Wendy Cassidy, senior counsel supervisor for the MCAD, agreed that their rules for evidence are less strict than they would be in court.

“It’s not like we don’t look at evidence,” Cassidy said. “It’s that we have relaxed rules of evidence.”

However, she added, that doesn’t mean they aren’t subject to review. The hearing officer for the case determines whether evidence brought up by either party during the hearing should be allowed. If the case is appealed, the full commission will also examine the evidence presented. If the case is appealed in the courts, the evidence is once again examined there. Cassidy says it’s rare that cases are sent back to the MCAD due to evidentiary errors.

“The full commission wants to get it right,” she added.

The charge: The MCAD’s appeals system is designed to be stacked against the respondent

If you lose a case in court, there are grounds on which you are entitled to appeal the ruling. For example, if you lose a case in one of Massachusetts’ district civil courts, you may be able to appeal to the appellate division. There, a panel of three judges will hear your appeal and make a determination.

If one of the parties involved in an MCAD decision does not like the outcome, they may appeal the decision as well. Doing so puts the case in front of the full commission. This is where Green is expecting to lose. His belief is that the MCAD has already decided how it will rule on a case, and it will not change its mind.

Cassidy said that an MCAD appeal is not a new trial. Instead, the full commission is looking to see if the hearing was properly executed, or if there was an error in either procedure or judgment.

“The full commission is looking at the record,” Cassidy said. This record includes what happened from the certification of the case (post-investigation) through the hearing. It does not include matters from the investigation stage unless those issues came up in the hearing. She noted that the MCAD’s review process mirrors the state appellate court standard of review.

The commission that reviews the hearing does not include the original hearing officer for the case. However, the commission’s rules of procedure specifically state that a hearing commissioner may be one of the three main commissioners, or a designee. Appeals may be before the full commission, which may be all three commissioners, or just two of them. This seems to leave the door open for participation by the original hearing officer if the group were so inclined.

Cassidy also noted that if either party is unhappy with the decision in the appeal, they are entitled to appeal the matter in the state Superior Court, where the hearing is reviewed once more. Aggrieved parties after this point are entitled to present their case to the state Appeals Court. After this, they may be able to present their case to the Supreme Judicial Court, though this is not a guaranteed entitlement like the appeals in the other courts are.

Discussion: What Needs to Happen with the MCAD?

We’re lucky to work in a state (and country) that has such strong protections against personal discrimination. Preventing and remediating discrimination is important work. The MCAD is not a perfect entity. There are systemic problems that exist within the structure of the MCAD, not the least of which are its staffing levels. Certainly, with more staff, more could be done. Backlogs could be eliminated; hearings could be handled more efficiently. But our conversations with the MCAD indicate the group is working to improve.

The optics of the MCAD can be a bit murky. For instance, in many cases, the MCAD provides the attorneys for the complainants. They provide the judges (hearing officers). If they win, they take some of the money for legal fees. And while the MCAD only hears the cases it thinks have probable cause for discrimination, and dismisses the others after investigation, at least one person has called the system designed to fail respondents.

Conclusion: Know the Laws Against Discrimination

But no matter how anyone feels about it, the MCAD remains a legal avenue for those looking to get justice when they feel they have been discriminated against. The MCAD’s decisions may be appealed, but if you lose those appeals, the damages that were awarded are legally binding. When you add in legal fees, that can be an incredibly costly error to make.