In-Depth: New England Drought Signals Need for Pricing Reform

| . Posted in News, policy - 0 Comments

Drought conditions in New England are either natural variation or part of climate change, but either way, it’s time we start pricing water differently in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Landlords may be surprised to know that despite the New England drought, water prices in Massachusetts haven’t changed. In this article, we'll go in-depth and propose moving away from the current Soviet-style annual budgeting process and toward floating water rates. We also evaluate one idea for a “drought surcharge” that might be more progressive than a flat rate hike, at the cost of increased bureaucracy.

How Bad is the New England Drought?

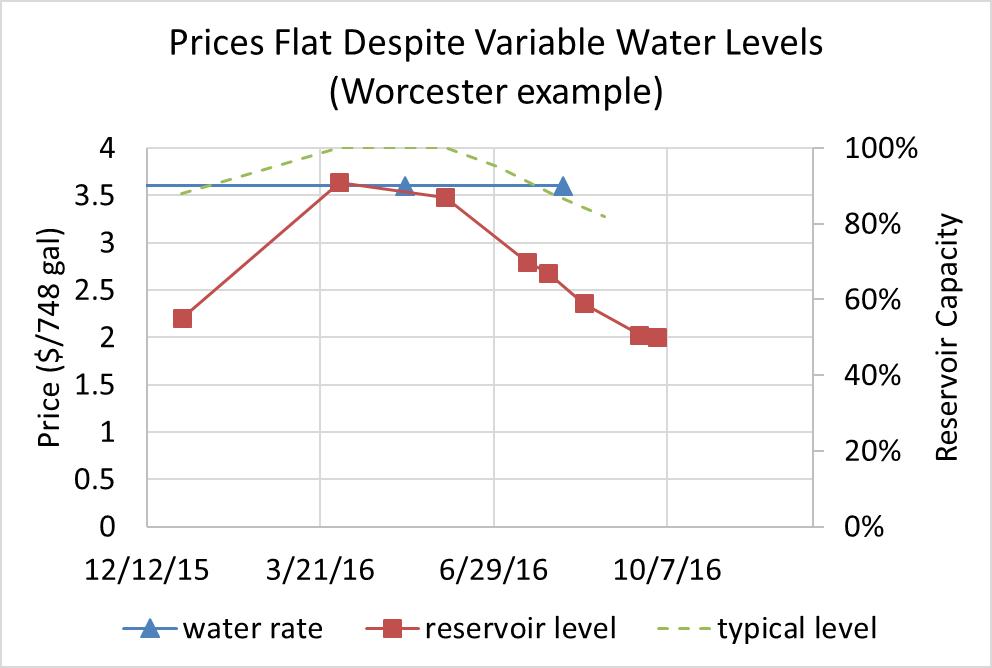

Central Massachusetts and many other parts of the Commonwealth have been under water use restrictions for months. What started as a “drought warning” became a “drought emergency” by early fall. Low snowfall last winter and little rain this summer have contributed to concerningly low reservoir levels.

According to the City of Worcester website, reservoir capacity drains over the summer. Reserves stood at 70% on July 18. In an average year, reserves don’t drop below 88% by August 1. As of October 1, they were at 50%. Central Massachusetts has had 30% less rain this year than the long-term average.

At first, Worcester officials asked residents to be “mindful of runoff,” and to “conserve.” Soon they had banned all outdoor water use and had stopped serving tap water in restaurants. This was “stage three” drought. (We don’t want to know what “stage four” looks like.)

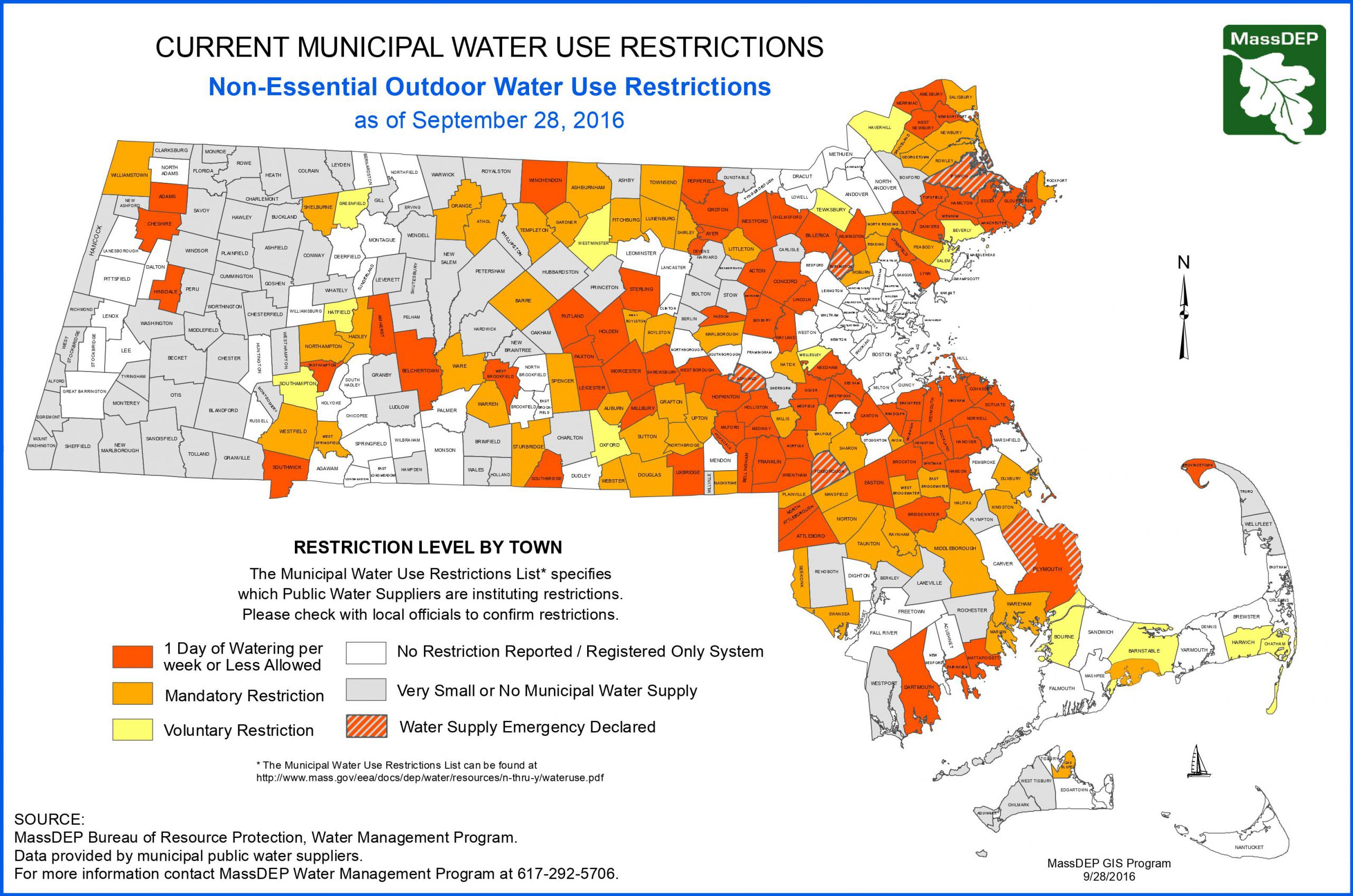

As of September 28, 2016, half of Massachusetts municipalities had enacted serious restrictions on private water usage.

Are we out of the woods? No. “Droughts are multi-year events. This one will be felt for longer than one season,” according to Janet Lathrop of UMass. We have an ongoing water shortage in New England.

Conservation is Important…

In California, a state with intense demand for water, conservation efforts have reduced urban water usage by 25%, according to one official speaking off the record. This follows decades of population growth during which water use remained flat, despite the state growing by over one-third in residents. There’s a lot to be gained through conservation.

California is a role model for conservation. They regulate the design of large paved surfaces like parking lots to ensure much of the rainwater that falls, when it falls, finds a path down into the soil, back to the water table, instead of being funneled out via storm drains to treatment plants and the sea.

…But Conservation Has Two Serious Drawbacks

Water conservation is very important, but it has two serious drawbacks.

First, conservation is ultimately a moral appeal. “Please use less water!” The haphazard fines we levy are equivalently weak motivators. One restaurateur caught washing his sidewalk in Worcester was fined, and it made the Worcester newspaper. He was embarrassed. But few others were caught and fined, and many kept wasting water with impunity. Moral appeals influence only some of us.

Second, conservation reduces water use, while fixed costs remain the same. It doesn’t matter that less water is flowing through our pipes, they will still break with the same frequency. A 25% reduction in water usage, system-wide, would have to correspond to some proportionally large increase in water price, on a per-gallon basis, just to maintain the fixed cost infrastructure. Prices have to rise no matter what.

Pricing is Key

When we charge more for something, people use less of it across the board. This is why we have a cigarette tax (to force people to smoke less). Forbes wrote about charging more for water in the context of California’s drought.

In Massachusetts, water prices are set for the year in advance by state and municipal agencies. Prices are based on the central planner’s data from past years and on their “crystal ball” forecast for the future. This is Soviet planning at its best. (Remember your history: Soviet planning didn’t work.)

Because of our laws and policies, we were not able to change the prices this summer when we saw the New England drought coming. All we could do was plead.

Price Controls Cause Shortages

Economist Milton Friedman said, “Economists don’t know much, but there’s one thing we know very, very well. And that’s how to produce shortages. Tell us what you want a shortage in. If you want a shortage in lettuce, we’ll set a maximum legal price for lettuce below the price that prevails in the market. And I guarantee you’ll have a shortage of lettuce."

A “stage three” drought in New England is a shortage of water, or the appearance of a shortage of water with respect to foreseeable demand. It isn’t profitable for anyone to get water elsewhere and sell it to us. It’s still profitable for us to keep using the same amount of water we always have. Until it’s all gone.

By not being able to change prices mid-year, we have essentially set a legal maximum price for water below the market price. Add a little variability from nature and voila!, we have a shortage.

We Must Let Water Prices Float

Every expectation is that the drought will persist into next year if not the next several years. Manmade climate change may make this experience considerably more dramatic than any in our recorded history.

Cities, towns, and the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority must start increasing their prices in response to water usage.

Water Pricing is a Domestic Affair

According the US Geological Survey, 90% of Massachusetts residents receive their water from the public supply (as opposed to wells), and two-thirds of this is surface water. Six times more water is used for household consumption than for agricultural irrigation. The only bigger use of water is in our power plants, in the form of once-through cooling. This returns almost all of the water to its source (albeit at higher temperature). This means that pricing of water to consumers and businesses is the primary lever we have to reduce state-wide water consumption via economic means.

Drought Pricing Needs Signaling

Suppose we do allow water rates to change regularly. A primary feature of functional markets is that prices are visible before a consumer chooses to partake of a service, or before they choose how much to partake.

It would therefore be best to transmit the pricing signal to the point of consumption. A small wireless digital display might be placed in homes to show the latest water price, or a sparkline graph of price. The technology used in “smart meters” that transmit household data to the city could be used in reverse, to transmit city data to the household. Except it could be as small as an Amazon “dash” button, since no water metering is required. This “communication” strategy could be carried out via the media, but having a “water price” at the kitchen sink would be the most impactful.

Pricing Decisions Must Consider At-Poverty Households

Progressives argue that unlike lettuce, water has no substitute. They say we therefore cannot charge the true cost of water, or rather, cannot make water any more expensive. There is a logic to this. Consider the following:

The City of Worcester is currently spending $1.7 million per month, according to one official speaking off the record, to purchase water from the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. Normally the city pays $0 for its water. If the city were to charge its residents for this increased cost of water, it would have to charge each resident an additional 31 cents per day, or $9/mo. For a household of three, that’s financially equivalent to doubling their electrical bill. Water is so cheap that small changes can have big percent impacts on the poor.

Under MGL Ch 40 Section 39L, it is illegal to give a “volume discount” for high water usage. The lowest rate offered is the one paid by the smallest consumers. So we already have a progressively tiered pricing system in Massachusetts. We would need to make sure, in allowing water prices to float, that the system remains progressive.

Why Do Landlords Care?

Landlords are a major reseller of water in Massachusetts. Unless we have been able to take advantage of Massachusetts’ difficult submetering law, water is included in our rents. We don’t want the water to run out, or we’ll have 800,000 angry customers.

If fines are in place, then tenants who use water illegally may cause fines to be levied against the property owner. City officials rarely if ever track down the tenant to issue or collect a fine. The landlord is, on the other hand, easily identified and made to pay.

If tenants are using water, and water prices have been allowed to increase, landlords can more easily justify the capital expenditure needed to submeter their buildings. This will, over time, put pricing pressure back onto the end consumer (the tenant) and help with conservation efforts.

The final, largest point is freedom of consumption. Many of us maintain lawns, upgrade our landscaping, and wash our sidewalks and exteriors. If we believe the current price of water is such that these expenditures are justified, we should be free to continue doing so without risk of fines or public shaming. With market pricing, we each decide which uses are allowable for ourselves.

What if we Don’t Want to Pay More for Water?

A novel idea was brought to our attention that we wish to give some consideration here. We could, if we really don’t want to pay more for water, create a revenue-neutral Massachusetts water tax or “drought surcharge” that would offset real estate taxes, up to the amount of the real estate tax.

How a Revenue-Neutral Massachusetts Water tax (Drought Surcharge) Could Work

There are two parts to this idea:

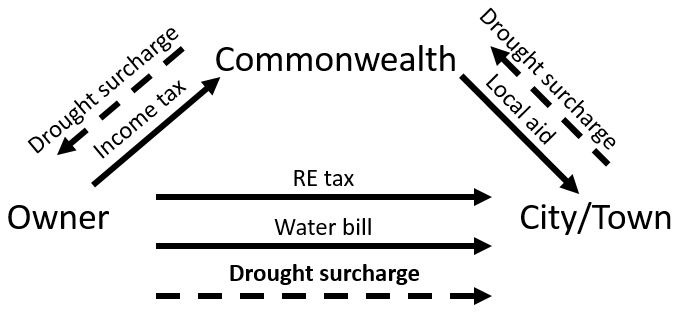

Part One: When a drought warning is issued, the drought surcharge would go into effect. The surcharge is a multiplier on water rates. Water rates are set in advance by the local water authority, but the surcharge could be allowed by new legislation to change monthly, weekly, or even daily. The multiplier would start at zero when reservoir levels are at normal capacity, and increase to some arbitrarily large number (say 100x) as reservoir levels trend toward zero. This surcharge provides a legal mechanism to change water rates daily without untangling the opaque way water rates are currently calculated and set. The surcharge is passed through by the water agency to the municipality in which the property pays taxes.

Part Two: On the next year’s income taxes, a new Massachusetts schedule can allow homeowners to claim back the water surcharge, against income taxes, up to the amount of real estate tax they paid to their local municipality. Say your normal water bill is $1,200 for the year, the drought surcharge amounted to $360 in additional water cost, and you paid a $3,000 in real estate taxes. Then your income tax bill will be $360 lower (a direct credit). You paid a lot more for water last year, but you come out even. It looks like you saved money on income taxes.

Why this works

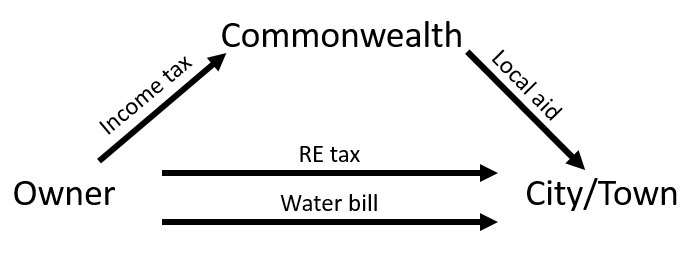

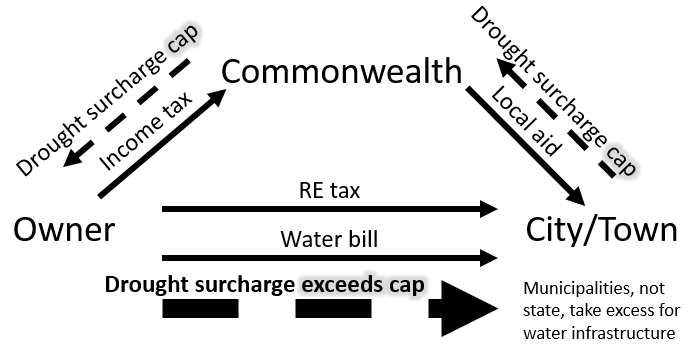

This works because money is already sloshing everywhere in every direction. Owners pay municipalities and the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth charges owners and pays municipalities. Municipalities charge owners and take from the Commonwealth.

The current state of money flow.

With a surcharge, we’re increasing or decreasing the amount of the usual flow. If the arrows point in the same direction, the surcharge adds onto the payment. When the arrows point in different directions, the surcharge reduces the usual payment. The surcharge just washes slowly in a big circle. Its effect is neutral, overall, but the timing calls our attention to drought. End users feel the pain of opportunity cost.

With a surcharge that's fully revenue neutral, funds move but no one pays/receives any more than before.

Three Advantages of a Massachusetts Water Tax (Drought Surcharge)

This proposal has several advantages: it provides a pricing mechanism to reduce water usage; it communicates the dollar impact of conservation to consumers; it is revenue-neutral in the early stages of drought.

First, the surcharge provides a drought-related mechanism to raise prices. Massachusetts water regulations are byzantine and fractured. We don’t have to dive into the laws or each city’s individual processes if we just layer on a surcharge. Raising prices reduces consumption, and the prices will be apparent on every quarterly or monthly water bill, so we know we will get the economics right. As prices increase, people will naturally feel the impact to their wallet and reduce usage. As we reduce usage, the surcharge falls back toward zero. No more shortage, no more pleading.

Second, the surcharge provides lots of penalty-free warning. If a surcharge were in effect, all of us with water meters would have felt a little pain already this summer. But because the surcharge is being rebated up to the amount of our real estate taxes, we haven’t been harmed. We will have floated a little more cash out to the government, which certainly may be painful, but we will get it back soon enough, in as little as three months, when we file taxes.

Third, the surcharge doesn’t amount to a tax unless we sink into a serious water shortage, or any one of us uses a disproportionate amount of water. In this situation, the surcharge will exceed the amount of our real estate taxes. This will cap our tax refund, so we will pay for our wastefulness. The fear of hitting the cap will encourage sharper conservation and/or finding alternative suppliers. If one person decides to keep using water above their cap, they can make that choice and pay the price; meanwhile the conservation efforts of others will keep reservoir levels high.

With a drought surcharge that exceeds the cap, the excess funds accumulate at the water provider.

The Disadvantages of a Massachusetts Water Tax (Drought Surcharge)

The disadvantages seem to be that we might move money away from municipalities, charge the poor more for water, and/or make a lot of busy work for ourselves. Are these disadvantages real?

First, let’s look at whether municipalities end up worse off. If someone decides not to conserve and ends up paying more than they can claim back, the surcharge becomes an actual tax for that person. In this case, the extra money remains with the local municipality responsible for the water infrastructure, drought enforcement, etc. (If there is a water authority interacting with the city, we need another box and arrows, but the concept is the same.) Funds are not taken from, and may in fact be given to the cities and towns who maintain water infrastructure.

Second, let’s see if this surcharge is regressive. Would the poor pay more? No. As stated above, changes to water pricing must consider low-income households, and can be designed to have minimal impact at the lowest pricing tier. For instance, the lowest consumption tier, which encompasses all low-income households, could be charged one-tenth the surcharge of higher consumption tiers.

Finally, does this system create administrative burden? Yes, and how much burden remains a primary question. First, we’re already sending out letters and emails asking consumers to conserve. That effort might be redirected to administering the surcharge. The information systems that currently produce water bills or other financial interaction statements between the various parties can be adapted, but we don’t know at what cost. For instance, water bills will have to multiply the final number on the bill by the surcharge. It’s more work to have a new tax schedule, as well. It might be better to dive into the water regulations and allow pricing to float. Either way, we have options to consider.

Conclusion

The economics demand increased prices during drought. This creates incentives to bring water in from other sources and more incentives for each of us to reduce our water usage. If we can’t bring ourselves to charge more for water directly, then the Massachusetts water tax or “drought surcharge” could be a revenue-neutral, progressive, and administratively feasible middle ground.

In conclusion, water is essential. We take it for granted. Let’s start charging people what it really costs before we run out of water in this New England drought.

Do you know about water pricing? Tell us what you think: info@masslandlords.net.