Estimates of Post-Moratorium Eviction Filings Now Exceed Housing Court Annual Caseload

| . Posted in News - 3 Comments

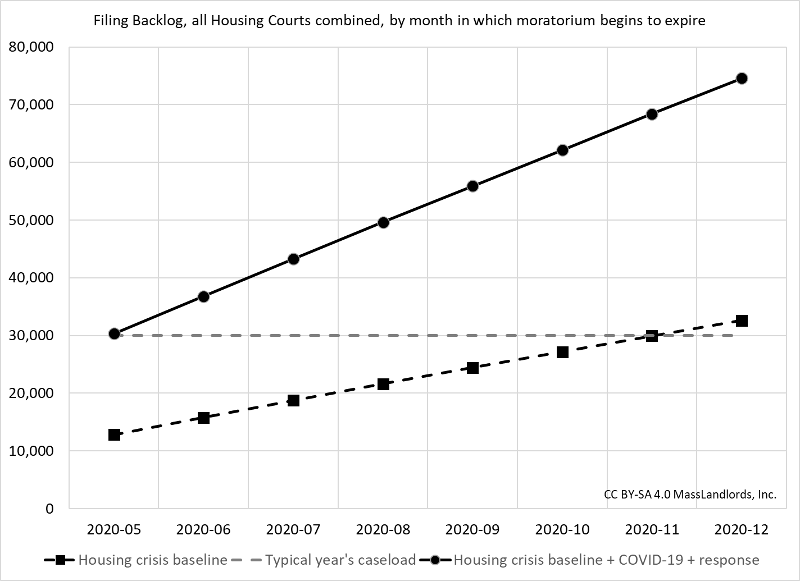

MassLandlords has compiled a detailed estimate of the number of eviction filings expected when the Massachusetts eviction moratorium ends. The estimate begins with the “normal” rate of filings during the housing crisis and adds onto this survey data (consistent with rent collection data) for additional cases arising from COVID 19 and our governmental responses (hereinafter simply “COVID-19 and our response”). The number of filings will be not less than 30,000 if the state of emergency is lifted now, and not less than 70,000 if the state of emergency continues to January.

The number of cases that are expected to be filed, by month in which the moratorium begins to expire. Graph assumes expiration happens by Governor cancelling the state of emergency, which starts a 45-day clock before notices can be served, and 14 days before any cases can be filed. CC BY-SA 4.0 MassLandlords, Inc.

This range can be viewed in the context of normal caseload for a year, which is 30,000 cases. The uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 and our response ought to make policy makers sit up and take note at the need to pay arrears and/or open the courts.

Eviction Moratorium Background

The Massachusetts eviction moratorium does not provide funding to pay rent arrearages, it simply sidelines the courts, preventing almost all mediation, filing and hearings. The moratorium lasts until either the moratorium expires (August 18) or 45 days after the Governor cancels the state of emergency, whichever comes sooner, unless extended by the Governor.

At time of writing, there was no indication from the Governor that the moratorium would be allowed to lapse. In other words, the moratorium is expected to last as long as the state of emergency, which is to say, as long as COVID-19 remains a concern.

Estimate One: Housing Court Data Baseline

Massachusetts eviction data from the 12 months prior to the start of the state of emergency (March 2020) provide a look at the “housing crisis baseline”, before COVID-19 and our response. Each month prior to the state of emergency, 2,500 summary process cases were filed each month statewide. If the economy were no worse under the state of emergency, then at least that many cases would need to be filed per the baseline in order to keep up with the housing crisis. Since we know the economy is much worse under the state of emergency, this number gives a lower limit of filings.

In addition, the Housing Court started deferring non-emergency cases March 13, 2020. Between that time and when the Massachusetts eviction moratorium was signed into law on April 20, 2020, 2,300 summary process cases were filed that are now continued (paused) pending resolution of the state of emergency.

If the state of emergency were fully lifted at time of writing (in May), it would be another 45 days before any notices could be issued, and at least another 14 days before any case could be filed. This would mean cases from March through July would still have yet to be filed, a total of 10,500 new cases from the baseline. Add to these the 2,300 continued cases.

At least 12,800 cases are pending from activity unrelated to COVID-19 and our response. Each month that passes after May adds another 2,500 baseline cases.

Estimate Two: MassLandlords Survey Data

Massachusetts rent collection data from participants in the MassLandlords rent collection survey show a cumulative March-May default rate of 19.2% (n = 3,030 unit-months). (Twitter followers note that this is down from the initial 30% preliminary data tweeted May 19.) Survey data may be biased toward nonpayment, but this result is consistent with various other non-survey datapoints including a Wall Street Journal Zillow article (31% nonpayment by April 5) and RentHelper data. A separate MassLandlords survey “Eviction Moratorium Survey Results: 22% of Providers Unable to Pay for Housing” is also consistent.

According to the most recent census, there are approximately 1,100,000 renter households in Massachusetts, of whom approximately 143,000 live in state or federally subsidized housing and may be assumed stable for the purpose of this analysis. The remaining market households (957,000) currently do not receive any housing-related assistance (although they may receive unemployment, stimulus, etc.). If the 19.2% nonpayment scaled to these market households, then approximately 180,000 households are now in arrears despite stimulus.

How much of these arrears are normal? Data from the National Multifamily Housing Council Rent Payment Tracker show nationwide arrearage at 7% to be “normal” (April 2019). We therefore remove 7% from the 19.2% and consider 12.2% the additional arrearage due to COVID-19 and our response (117,000 households).

What percentage of arrearages result in a filing? In Massachusetts, April 2019 saw 2,500 cases, or only 3% of “normal” arrears. If the 2019 ratio applies, then an additional 3,500 households per month will be triggering filings. Note that under the climate of COVID-19 and the eviction moratorium, landlords may decide less or more frequently to file evictions than at any other time. This inclination is not known and will likely vary by the individual.

At least 14,000 cases are already pending due to COVID-19 and our response. Each month that passes adds another 3,500 cases due to COVID-19 and our response.

How Does this Compare with Housing Court Caseload?

The Housing Court staff are currently able to process 30,000 cases per year. The day the eviction moratorium expires, the entire backlog would likely be filed at once.

How likely? Landlord perception of the eviction moratorium is very poor. An April 16 survey of members (n = 116) showed a 50-50 split as to whether an eviction moratorium was a desirable public health response to COVID-19. Two-thirds of members opposed or strongly opposed the specific moratorium enacted. Landlords generally have not qualified for or received public funding, leaving eviction the only option to avoid insolvency.

If the state of emergency were rescinded at time of writing in May, such that the moratorium expires in June and the first notices were served in July, the Housing Court staff would be asked to handle a year’s-worth of cases in that first week of filing. If the moratorium lapses in August, then 18 months’ worth of cases would be filed in that first week. If the moratorium lapses in January, then two years’ worth of cases would be filed in that first week.

The Housing Court will need to hire substantially, or else reduce the amount of work required to decide a case, or else extend case duration to many multiples of normal. Considering that Housing Court staff play an essential role in mediation and alternative dispute resolution, the eviction moratorium seems in retrospect to have been overly quick to sideline this entire branch of civil service. A variety of strategies could have already been employed to address many of these arrearages.

The District Courts (not elsewhere contemplated) process approximately 10,000 summary process cases per year. Cases that cannot be dealt with by the Housing Court may be redirected to District Courts. It seems unlikely that District Courts will be any better equipped to ramp up for the deluge of filings.

Will Opening the Economy Help?

A return to normal economic activity will not impact the results for a May or June expiration, which already account for normal recovery from arrears. Note that the number of filings (30,000 for a May expiry) is below the total arrearage (180,000). Specific policies must be enacted (e.g., A Fair and Equal Housing Guarantee via Surety Bonds) to cover all unpayable arrears or else the backlogged cases will be filed.

Furthermore, until COVID-19 ceases to be a concern, certain economic activities will likely continue to be disallowed (e.g., restaurants, attendance at sporting events). These sectors will be entirely unable to offer dependent households a return to normal earnings, let alone an operating surplus to cover arrears. Many renter households operate in service industries that remain shuttered or else at reduced capacity.

Post-Moratorium Eviction Filings Conclusion

The disruption of the unfunded eviction moratorium has been severe.

If the moratorium ends reasonably quickly without funding, then the Housing Court will need to double or triple in size to process the backlog of cases with normal quality and duration.

If funding along the lines of surety is enacted, then existing arrearages would be covered as well as future arrearages, however long COVID-19 and the moratorium last. The shut-down of the courts could continue (at least as far as nonpayment is concerned) without serious impact to owners or renters.

If funding is not secured and the moratorium remains in effect, the model will break when key assumptions are rendered inaccurate. For instance, there is no reason why the 3% file rate on arrearages should continue in the face of no public support. Landlords are entitled to file on 100% of arrearages, and may feel it best to file against both the renter and the Commonwealth for having exacerbated the magnitude of the loss. Hundreds of thousands of cases more than are estimated here are possible, potentially leading to disruptions to a third of the rental housing in Massachusetts.