Boston Bans Airbnb for Investors

| . Posted in News - 2 Comments

On June 13, 2018, the people of the City of Boston through their City Council banned short-term rentals except under a few allowable circumstances. The effect is to ban short-term rentals for all investors. At time of writing, the ordinance required signing by the Mayor, who was expected to sign.

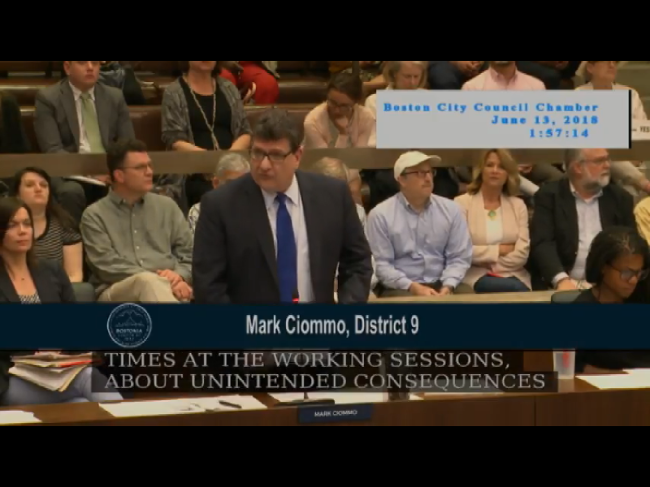

Boston City Council hearing June 13, 2018. Grainy footage shows Councilor Mark Ciommo saying: "I can't support the recommendation from the committee report [ought to pass] without the investor units because I believe what I've said many times at the working sessions about unintended consequences... [There are only 419 multifamilies in the downtown core.] Counselor Wu expressed one of my biggest fears that there's going to be agents out there contacting every owner occupant trying to get them to list... We're incentivizing a new business model without having any competition, any downtown availability."

Arguments in Favor

The preamble to the City Council Docket #0764 referred to the three primary points made in favor of the regulation.

First, proponents argued that short-term rentals offered to the public ought to comply with all standards applicable to housing, especially safety. Without the regulation, they said, there would be no mechanism to enforce smoke detectors, two means of egress, lead paint safety or any of the other safety measures required in Massachusetts housing.

Second, they argued that long-term residential vacancy rates are low. Especially elderly and low-income residents are being displaced by rising rents, renovation, and new development. Proponents said Airbnb, Home Away, and other short-term rental services were major contributors. Without the regulation, long-term rentals would be converted into short-term rentals and additional housing stock removed from circulation.

Third, supporters argued that neighbors are impacted by “quality of life issues.” Particularly irritating were disrespectful short-term renters partying, making noise, or otherwise intruding upon the quiet enjoyment of long-term renters and neighboring owners.

What the Ordinance Actually Does

The ordinance defines short-term rentals as any rental for 28 consecutive days or less. It establishes three classes of short-term rentals: home share units, limited share units, and owner-adjacent units.

Home share units are units of up to five bedrooms rented by the owner in their absence.

Limited share units are units of up to three bedrooms rented by the owner while remaining in one of the bedrooms.

Owner-adjacent units are one unit in a two- or three-family building, where another unit in the building is occupied by the owner of the building.

All other types of rentals are illegal. You cannot rent more than one unit in a three-decker, even if you live in the building. And you simply cannot rent any unit in a building where you don’t live.

There are two exceptions. One is when a hospital or non-profit reserves space to treat people for trauma, injury or disease. The second is when an LLC or an Inc. has a contract with an educational institution or a company to provide short-term housing (longer than 10 days per person). Either of these exceptions lets you operate without being subject to this ordinance.

Boston’s short-term rental ban will take effect on January 1, 2019. There is a sunset provision for existing short-term leases, but it’s not clear that anyone would qualify for it. Existing units contracted for short term rentals as of June 1, 2018 may continue to operate until the contract ends or September 1, 2019, whichever is sooner.

Arguments Against

The ordinance seems unlikely to meet its intended goals.

First, let’s consider the issue of inspections and safety. All units offered for rent – whether on a short- or long-term basis – must be safe for those who rent them. The ordinance is correct to subject short-term rentals to inspection, consistent with Boston’s long-term rental inspection requirement.

The ordinance as adopted, however, will fail to make all rentals safe. Airbnb rents are typically twice what long-term rents are, when calculated on a per-night basis. There is a large economic incentive for investors to enter the short-term black market by offering their short-term rentals via word-of-mouth or other untrackable channels. A black-market rental is by definition not going to be inspected. And since this kind of market offering will only attract operators who willfully or incompetently skirt the rules, it is almost certain to be non-compliant with safety code. The ordinance as-written therefore flies in the face of a history replete with examples of over-regulation having unintended consequences. The ordinance will create unsafe conditions for some or many.

Second, let’s consider the issue of vacancy rates. Boston in particular, the Commonwealth more broadly, has failed to permit new construction and subdivision at a level that would sustain affordable housing. Housing is much too expensive because the demand has grown much faster than the supply. There is definitely a need to do something about the housing supply.

The ordinance as adopted, however, will fail to make any measurable impact on rent levels. A paper published March 29, 2018 by Kyle Barron, National Bureau of Economic Research, Edward Kung, UCLA, and Davide Proserpio, Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California, “The Sharing Economy and Housing Affordability: Evidence from Airbnb,” proves the point. The researchers found that for every 1% increase in Airbnb listings, rents increase 0.018%. If Airbnb doubles (a 100% increase), rents will increase 1.8%. On a $2,000 apartment, this is $36, a trivial amount for a huge increase in Airbnb. Zoning decisions from the last 30 years, on the other hand, probably have contributed over $1,000 to rent increases in real dollar terms.

Finally, let’s consider the issue of quality of life. Airbnb’ers have more fun and make more noise than long-term renters. Airbnb is largely a vacation rental service. Renters coming into town for vacations and weddings are likely to be irritatingly happy, noisy, and/or light-heartedly destructive.

The ordinance as adopted permits owners to rent out their homes and leave. This is worse than the average investor, who has business process concerning ongoing security, security deposits, screening renters, and enforcing house rules. If investors were failing to meet these obligations, they could have been regulated or had process imposed on them the way landlords do. Instead, the keys have been handed over to an absentee owner to hand to an unchecked renter. The ordinance will not eliminate quality of life issues.

Hastily Drafted Exceptions Open the Door Wide to Abuse

Given the lucrative appeal of Airbnb, we should consider one final, half-joking issue: The two exceptions to the ordinance combine with existing privacy laws to open the door wide to abuse.

For instance, consider the non-profit exception. The ordinance reads, “The use of a dwelling for which a contract exists between the owner and a … non-profit organization registered as a charitable organization with the Secretary of the Commonwealth…that provides for temporary housing in such unit of individuals who are being treated for trauma, injury, or disease, or their family members, shall not be considered a Short-term Rental.”

It would cost only a few thousand dollars for an Airbnb investor (or consortium) to set up their own non-profit, establish a contractual relationship with their LLC, and open their door as a treatment center. Consider the stress of a grueling nine-to-five and a bad boss. Doesn’t that count as workplace trauma? Wouldn’t a weekend in Boston be necessary rehabilitation?

A doctor would not be required to sign off on this crooked arrangement. Under MA law and precedent, a licensed clinical social worker, school teacher, hospital administrator, or any of a half dozen sources would have standing to grant eligibility to vacationers-turned-patients. The investor or consortium could hire their own LCSW, if they had enough units under operation. Under medical privacy law, it would be a long legal slog for the City or any other agency to argue that patients weren’t really being treated. In fact, the Airbnb operator and the City would probably be barred from knowing the exact clinical details. This is the same loophole that plagues landlords concerning emotional support animals.

Consider also that non-profits are notoriously hard to fix. The only regulation that can be brought to bear on a non-profit is via the Attorney General’s office, and by reputation that office is known to be far too busy to police gray-area or small-fry issues. The current AG, for instance, devotes significant attention to large, federal issues. A non-profit whose staff earnestly believed they were helping people recover from injury, trauma, or illness would be very hard to identify and shut down.

Since the ordinance explicitly allows for family to come with the convalescent, an Airbnb clinic operator would only need one individual with only one trauma, injury, or disease to qualify an entire group of people for a stay. Any chronic disease, like arthritis, would suffice. In fact, under current wording, any injury would suffice, as well. Stub your toe? You deserve a night at Fenway Park! Bring your whole family.

You should not set up a crooked nonprofit. But someone else may well. With this one small unintended consequence, we have amicrocosm of how foolish and ill-conceived the whole ordinance really is. We will leave it to readers to imagine what might be done with the second exception.

Councilor Ciommo brought up other unintended consequences that may be more probable, see image caption.

Hotel Industry Role Unknown

The Massachusetts Lodging Association, a $600,000 a year trade association whose mission is to protect the interests of hoteliers, issued a statement following the ban. The statement inveighed against “wealthy, out-of-town” real estate investors and gushed over the “true leadership” of the City Council.

The hotel industry might have been feeling pressure from Airbnb, which offers travelers an alternative set of amenities: kitchens, multiple bathrooms, and residential surroundings.

Despite the Lodging Association’s harsh words against “wealthy, out-of-town” investors, nothing was said about any of the new hotels being built in Boston, least of all the extravagant $375 million Raffles Tower. This development will be half hotel, half luxury condos, zero percent affordable housing, built by a Singapore company that offers 24-hour butler service.

It’s unclear whether the Massachusetts Lodging Association or other hotels will disclose lobbying expenditures following this ban. Either way, the hotel industry has come out ahead in this public debate, and has managed to avoid being tarred with the same brush that smeared Airbnb investors.

Airbnb Ban Conclusion

Airbnb and our fellow short-term investors are likely victims of politics, shaky math, and special interest lobbying. The City of Boston, following the failed home rule petition for Just Cause Eviction, might have wanted to look tough on real estate investors. No one seemed to care that Airbnb has a negligible effect on rent levels compared to zoning. The hotel industry came out smelling like a rose, and hugely better off.

Boston’s short-term rental ban is another example of good intentions carelessly executed. The safety concerns were real. But the majority vote masked legitimate concerns of a vocal minority who are now legally out of business. The result falls far short of consensus and therefore, far short of good public policy.