CDC Eviction Moratorium Off Again Following Supreme Court Decision

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

The on-again, off-again CDC eviction moratorium is officially off again. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium, which had been temporarily reinstated on Aug. 3, 2021, for United States counties registering “substantial” or “high” levels of COVID-19 transmissions, has been effectively declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. On August 26, SCOTUS, via a per curiam opinion, effectively ruled in favor of the Alabama Association of Realtors in their charge against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (which includes the CDC) that the moratorium was illegal.

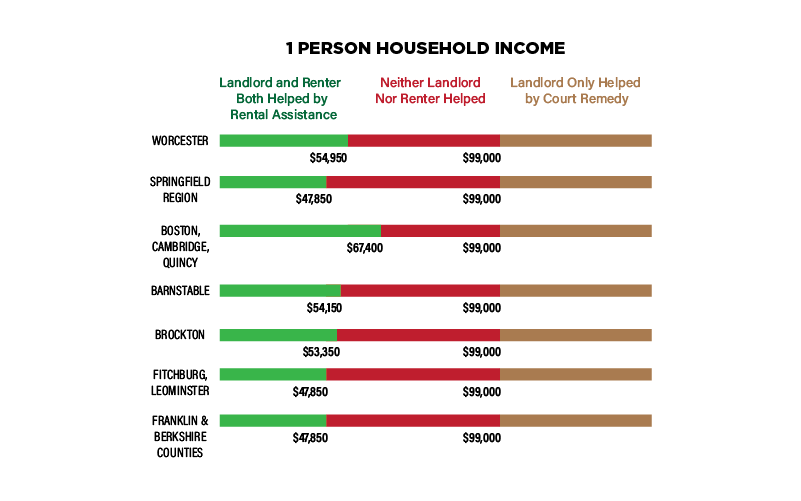

With the CDC eviction moratorium in place, renters with income above 80% of AMI were both ineligible to receive government rental assistance and protected from eviction. This graph shows that gap (in red) for single-person households in various regions. cc by-sa 4masslandlords

Further litigation may follow on local and state levels, but the Supreme Court’s collective opinion means the end of the federal eviction moratorium imposed by the CDC in this form. In theory, it’s still possible for the U.S. Congress to pass a legally sound national eviction moratorium legislatively, but it’s unlikely in today’s congressional climate. Appeals to legislators by President Biden and others in late July for an eviction moratorium gained no traction.

Still, evictions remain in flux depending on where you live. Boston issued its own eviction ban on Aug. 31, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision. The ban was issued by the Boston Public Health Commission as part of the city’s Housing Stability Agenda, which will also include a $5 million Foreclosure Prevention Fund to help homeowners cover costs lost to the pandemic economy.

Other municipalities with eviction moratoriums in place include Malden and Somerville. Further local moratoriums may be reinstated or remain in place.

Alabama Realtors v. DHHS

Confusion seemed to swirl around the CDC eviction moratorium from the start, but it increased with the attempted reinstatement on Aug. 3. Details about who was protected by the moratorium were unclear, rental assistance has been slow in distribution, and the obfuscation wasn’t helped by the on-again, off-again actions by the CDC.

The CDC moratorium’s legality was put to the test in the case of Alabama Association of Realtors v. Department of Health and Human Services. The case came before the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, which issued a judgment vacating the CDC’s original moratorium on the grounds that it violated a section of the Public Health Act. However, the District Court stayed that judgment pending an appeal by the U.S. government. Meanwhile, the plaintiffs, in mid-summer 2021, requested a judgment on the case by the Supreme Court. The court at first refused to adjudicate the case, partly due to the fact that the original moratorium was scheduled to expire on July 31. When the CDC reinstated the eviction moratorium on August 3, the Alabama Association of Realtors again requested the Supreme Court’s judgment on the District Court’s stay. The Supreme Court then issued its per curium opinion vacating the District Court’s stay on its judgment that the moratorium was unlawful, rendering the lower court’s decision final and enforceable.

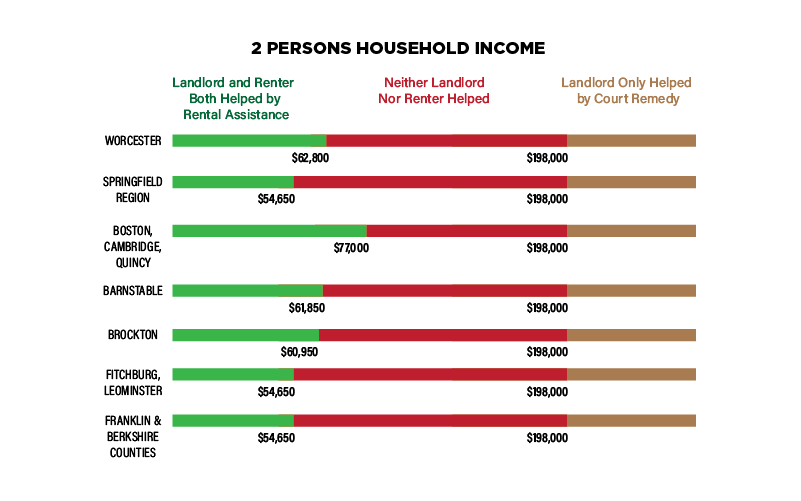

This graph displays an even wider gap, among two-person households, of renters with incomes over 80% of AMI, ineligible for rental assistance but protected from eviction under the CDC moratorium. cc by-sa 4 masslandlords

Eviction Moratoriums Positively Impact Covid Numbers

Meanwhile, the CDC has argued that in an unprecedented circumstance such as during a pandemic, its moratorium was essential to public health. By reducing evictions, more people will remain in their homes, thereby diminishing social interaction and congregation, and the resultant spread of Covid.

Several studies conducted since the start of the pandemic support the CDC claim. A January 2021 study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research concludes that policies limiting evictions reduce COVID-19 infections by 3.8% and deaths by 11%. Another study, written on Nov. 30, 2020, and published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, found that states that lifted their eviction moratoriums during the period of the study experienced COVID-19 incidents at a rate 1.6 times higher than those whose moratoriums remained in place for the first 10 weeks. That rate grew to 2.1 times at 16 weeks after lifting moratoriums. Mortality rates correlated roughly with incident rates for the study duration.

Moratoriums were found to be protective even after correcting for regional differences in mask-wearing, stay-at-home orders, testing and school closures.

Two Interpretations of the 1944 Public Health Act

The legal challenge to the eviction moratorium has been argued on statutory grounds, based on an interpretation of the Public Health Act. Section 264 of this 1944 legislation empowers the Surgeon General, “with the approval of the Secretary” (meaning, in this context, the Secretary of Health and Human Services), to “make and enforce such regulations as in his judgment are necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the States or possessions, or from one State or possession into any other State or possession.”

Court disputes were based on the next sentence of the section: “For purposes of carrying out and enforcing such regulations, the Surgeon General may provide for such inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, destruction of animals or articles found to be so infected or contaminated as to be sources of dangerous infection to human beings, and other measures, as in his judgment may be necessary.”

Some judges determine the totality of Section 264 to mean that the executive is limited by law to treating only animals or infected “articles,” and not empowered to regulate people’s behavior or commerce. Proponents of the eviction moratorium argue that the first sentence grants the executive broad authority to take measures as it sees fit to protect public health from disease, and is in no way limited by the second sentence.

The Supreme Court did not agree. “The CDC has imposed a nationwide moratorium on evictions in reliance on a decades-old statute that authorizes it to implement measures like fumigation and pest extermination,” wrote the Supreme Court in its per curium opinion. “It strains credulity to believe that this statute grants the CDC the sweeping authority that it asserts.”

No Distinction Between Vaccinated and Unvaccinated

The Aug. 3 moratorium had been issued partly in response to the unexpected national spike in Covid cases and deaths as the Delta variant has spread widely. It was also intended to forestall a possible onslaught of evictions and buy time for the continued distribution by states of more than $46 billion in federal rental aid, less than half of which has been paid out.

President Biden had been urged by rental advocates and others to extend the original eviction moratorium in the weeks leading to its final expiration. He demurred, citing the Supreme Court’s statement that a further extension would not be legally sound unless the U.S. Congress ratified such a moratorium. Congress took no action.

The new CDC moratorium was modeled after the first eviction moratorium except that it applied only to the 90% of United States counties with “substantial” or “high” levels of COVID-19 transmissions, according to a statistical calculation (defined below). The CDC recommends that people in those counties wear masks indoors, whether or not they are vaccinated.

One distinction between the timeframe of the recent moratorium and the original CDC eviction moratorium is the availability, since January 2021, of effective vaccines to combat Covid illness. Since then, nearly 60% of the U.S. population over age 12 has received full Covid vaccinations. (As of writing, the CDC recommends COVID-19 vaccination for all people aged 12 and older.) The CDC order did not distinguish policy between tenants who are vaccinated against Covid and those who are not.

However, the new eviction moratorium order acknowledged that the nationwide campaign to vaccinate people has been less effective among populations most at risk for eviction. It further emphasized that people who have been vaccinated can still contract Covid and transmit it to others whether or not they display symptoms.

Every Massachusetts County Except One

The reinstated moratorium had applied to approximately 90% of U.S. population areas. In Massachusetts, every county is experiencing substantial or high Covid levels except Hampshire County, which has a moderate transmission level at time of writing.

Transmission levels are calculated by categorical ranges of Covid cases per 100,000 people living in a county, or a rate of positive tests over a seven-day period. A county with 50-99 cases per 100,000 people, or positive tests of 8-9.9% over the past seven days, receives a label of “substantial” Covid transmission. Counties with 100 or more cases per 100,000 people or positive tests of at least 10% over the previous seven days are given a “high” transmission rating.

Among Massachusetts counties, Berkshire, Bristol, Dukes, Hampden, Nantucket and Suffolk are at high levels of transmission. All other counties, except Hampshire, have substantial levels.

Rental Assistance Funds Still Available

The new CDC eviction moratorium, like the original one, barred evictions of many renters for nonpayment due to verifiable COVID-19 economic impact.

According to a U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey conducted June 23 to July 5, there were some 11.4 million renters behind on rent payments across the nation. The same survey also found that more than 1.4 million Americans expected to be evicted within two months (at the time of this survey, the CDC eviction moratorium was not expected to be reinstated after July 31). Another 2.2 million considered it “somewhat likely” that they will be evicted.

Meanwhile, federal rental assistance distributed to states as part of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and previous Covid-relief packages has been frustratingly slow in getting to households in need. Through ARPA, funds in Gov. Baker’s Eviction Diversion Initiative and other programs, Massachusetts has had several hundred million dollars available for housing and rental assistance.

Much of that money remains unallocated as some states struggle to ramp up their rental assistance distribution infrastructures. Also, many renters and homeowners who are eligible for housing assistance have either not applied or misunderstand the application process, further delaying funding from getting to those who need it.

In Massachusetts, legislation was passed protecting renters from eviction who can demonstrate that they have submitted applications for rental relief.

Applying for Rental Assistance vs. Filing for Eviction

The Covid picture seems as unpredictable as ever with the Delta variant surging and a large percentage of U.S. citizens still unvaccinated. The Supreme Court’s clearing of the District Court’s invalidation of the CDC eviction moratorium does nothing to address an untenable pandemic and housing morass.

While predictions continue of waves of eviction filings after moratoriums are lifted, Massachusetts has not seen such spikes so far, such as following the expiration of the state’s eviction moratorium in October 2020. With hundreds of millions of rental assistance dollars left to be distributed in the state, we are hopeful that the infrastructural offices focused on that distribution will eventually catch up with the need.

Meanwhile, Massachusetts housing providers are encouraged to work with their tenants in applying for rental assistance whenever possible and when they qualify. Landlords are also allowed to apply for rental assistance directly on behalf of their nonpaying renters and those who owe back rent due to Covid economic impact. Either scenario, when possible, provides a better option than pushing through an expensive and often arduous eviction in which there are no winners.