The Power of Chapter 93A: An Airbnb Case Study Crossing State and National Borders

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

By Douglas Quattrochi

Massachusetts General Law Chapter 93A specifies the “regulation of business practices for consumers’ protection.” This is a powerful statute that awards triple damages, attorney’s fees and costs to consumers who were wronged by a business. As landlords, we face 93A claims from our renters. And I had a chance to see the law from the other side, as a renter myself. I will share my story of a vacation Airbnb in London, where I was a short-term letter, in their parlance (think “subletter”). I’ll show that the long arm of Chapter 93A stretches across state lines and even the ocean, not only for letters, but also for lucky landlords.

This was the smoke detector base station at Princess Road. Chapter 93A protects all commonwealth residents from all unfair and deceptive business practices. For instance, advertising an apartment with working smoke detectors but delivering this was a Chapter 93A violation. CC BY-SA Douglas Quattrochi

The Airbnb Was Not as Advertised

I live in Massachusetts, but I have family in London. Whenever the chance is given to me, I travel abroad to see them. It was for this reason that late in December 2021 I checked into an Airbnb on Princess Road, London.

I picked the Airbnb first on the basis of its proximity to family, but second on the basis of its having advertised a working smoke detector and a carbon monoxide alarm. In my professional capacity, I’ve known of too many killed by fire or exhaust to rent anyplace less.

After keying in, I found the smoke detector missing. In the UK, some detectors have a hardwired base station that chirps when the detector is missing. Someone removed the smoke detector, tore the base station from the wall, and left it hanging by a live wire, chirping for help. It took me some time to identify this as the source of the chirp. I wasn’t immediately familiar with this UK hardware, and the place was echoey.

I messaged my host. My host called me and admitted “Oh yeah, we noticed that before.” He asked if I would be willing to stay in the unit without a working smoke detector. I said no. He offered I could at least open the fuse box and deactivate the circuit to stop the chirping. I explained that I valued a working smoke detector. He said he wasn’t sure he could get anyone there to fix it for several days. I said I was cancelling the reservation. My host said he would not issue a refund. I said we’d discuss it after I found a place to stay for the night.

I left the premises exactly as I found them, with the keys in the lockbox, within an hour of checking in. All of that hour was spent investigating the chirping and discussing it with the host.

No One Gave a Refund

After much discussion, the host said he wouldn’t refund my reservation. That was sad for me, because if the host had refunded me, it would have ended our story and saved me a lot of time. But I’m sharing this story because here is where it gets interesting.

Airbnb's Guest Refund Policy effective December 15, 2019 stated that I would be entitled to a refund in this circumstance:

"If you are a Guest and suffer a Travel Issue, you are covered by this policy as follows:

"If you report a Travel Issue up to 24 hours after check-in, we agree, at our discretion, to either (i) reimburse you the amount paid by you through the Airbnb Platform (‘Total Fees’), or (ii) use our reasonable efforts to help you find and book for any unused nights left in your booking another Accommodation."

Travel Issues are defined as including:

"(c) at the start of the Guest’s booking, the Accommodation: ... (ii) contains safety or health hazards that would be reasonably expected to adversely affect the Guest’s stay at the Accommodation in Airbnb’s judgment."

The policy said Airbnb would refund or alternatively find me another accommodation. I had 24 hours to make a claim, so I found a hotel first and raised the claim with Airbnb the next morning. I had already found alternative accommodation. I needed a refund.

Long story short: Airbnb refused to issue a refund under their policy. In fact, they ignored their policy. Every time I cited it, they deflected. If they didn’t intend to follow their policy, this would make the policy deceptive. I told this to their various customer service people. No one listened.

I wrote the following to Airbnb customer service and in a print letter mailed to headquarters:

“Airbnb's denial of my request under this policy references neither this policy nor Airbnb's discretion called for in the policy. If Airbnb had actually attempted to argue that lack of a smoke detector was immaterial to my safety, Airbnb would still have failed. But Airbnb did not even make such an attempt. Rather than exercise its discretion with respect to safety concerns, Airbnb have attempted to ignore the Guest Refund Policy and force me to accept less than the policy offers. This makes the Guest Refund Policy and your actions deceitful.”

Deceit or deception is an important phrase in Chapter 93A. But first let’s look at whether I have standing to raise a Massachusetts claim in another country.

Massachusetts’ Legal Framework Dominated

There are three parties in this case: We have a Massachusetts resident alleging protections under Massachusetts General Law Chapter 93A, a London landlord operating under UK safety regulations and UK consumer protection laws, and a booking facilitated by Airbnb, a California company. Whose jurisdiction prevails? Short answer: Massachusetts’, because 93A is a hammer.

This case is simpler than it looks, for we can dismiss the landlord right away. I paid Airbnb, not the landlord. Although Airbnb is a California company, they have nexus in (operate in) Massachusetts. Therefore I have incontestable Massachusetts rights with Airbnb. Those rights are not limited to the particular country of my stay. We can therefore ignore the UK landlord and UK safety regulations.

This setup is relevant to all Massachusetts landlords. I was a Massachusetts resident talking with a company that operated in Massachusetts.

Airbnb’s Agreement Was Voided

Did Airbnb’s terms and conditions say I could sue them under Chapter 93A? No. The Airbnb Terms and Conditions, paragraph 22, “United States Governing Law and Venue,” actually called for the exact opposite. It said their agreement would be interpreted in accordance with the laws of the State of California. Furthermore, paragraph 23 called for arbitration.

Unfortunately for Airbnb, both of these clauses were in conflict with Massachusetts law. This rendered them void and unenforceable.

Chapter 93A Aims to Hammer Out Deception and Unfairness

General Law Chapter 93A is broadly written. It reads, without limitation,

"Section 2. (a) Unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in the conduct of any trade or commerce are hereby declared unlawful."

There are no ifs, ands or buts about it.

Is Airbnb engaged in a trade or commerce and subject to this law? Yes. G.L. Chapter 93A Section 1(b), reads:

"(b) ''Trade'' and ''commerce'' shall include the advertising, the offering for sale, rent or lease, the sale, rent, lease or distribution of any services and any property, tangible or intangible, real, personal or mixed... and shall include any trade or commerce directly or indirectly affecting the people of this commonwealth."

That’s very powerful. I could be renting an apartment on the moon and Chapter 93A would apply, because that “trade or commerce” would be “affecting the people of this commonwealth.” As long as I hadn’t moved permanently to the moon, I’d be protected.

All renters residing in Massachusetts are protected under Chapter 93A.

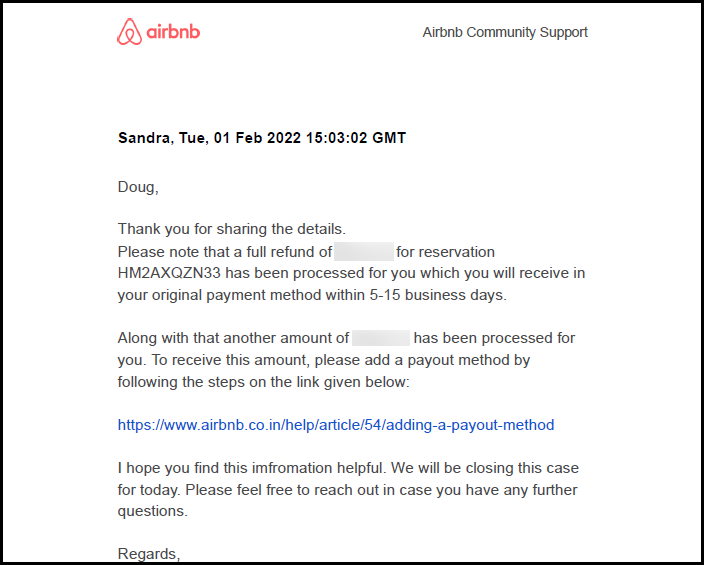

Chapter 93A often results in out-of-court settlements. In this Airbnb case study, the settlement letter clearly shows the amount paid was in excess of the Airbnb reservation cost. CC BY-SA Douglas Quattrochi

The Chapter 93A Demand Letter Got Me Refunded

I used all of the above to write a demand letter. A demand letter is the start of a lawsuit. The way Chapter 93A works, the business receiving the letter has 30 days to make a good faith offer of settlement. If they don’t, they could be ordered by a court to pay triple damages, attorney’s fees and costs.

Imagine! Airbnb refused to refund the cost of my deficient rental. As a result, they would have to pay me three times the rental’s cost, plus cover my attorney and all court costs. What a mistake it would be not to stand by their policy!

I mailed them my demand letter. I added up every penny of expense and inconvenience along the way, not just the cost of the Airbnb at Princess Road. And Airbnb settled. They paid 1x my full damages, which were more than just the Princess Road rental costs. If Airbnb had refunded me what I asked at the outset, they would have saved money. I didn’t have to go to court. If I had, I would have walked away with even more.

Chapter 93A Lessons for Landlords

Chapter 93A is a very powerful law for consumers to use against businesses in any of the following broad scenarios:

- A business practice is unfair, or

- A business practice is deceptive.

This means as a landlord you should always try to make full disclosures and treat all renters fairly. Specifically, landlords should note the following aspects of 93A:

- Your apartment ad must accurately describe what is for rent.

- All Massachusetts residents are protected from all unfair and deceptive practices.

- No written agreement can invalidate these protections.

- You need good customer service to avoid a Chapter 93A demand letter.

- Everyone on your team needs to give the same good service. Everyone needs to understand how Chapter 93A can spiral out of control.

- The first step in a Chapter 93A dispute process is a demand letter.

- If you get a demand letter, you have 30 days to make a good faith offer of settlement. Do it!

- If you end up in court, you may be ordered to pay three times whatever you should have settled for, plus attorneys’ fees, plus costs.

- Chapter 93A claims are preventable: Make full disclosures and be fair always.

Policy Implications for Chapter 93A

It should be noted that I did not hire an attorney either to draft the letter or to bring a suit. An attorney is not necessary. But I could have hired an attorney. If I had, I would have included the attorney’s bill as part of the damages in my demand letter. This is the final key point about Chapter 93A: Attorneys can get paid out of settlements without the courts ever being involved.

We saw this during the COVID-19 pandemic: Landlords who did not want rental assistance were sent demand letters by legal services. These letters alleged discrimination on the basis of receiving public assistance. The landlords settled in such as a way as to pay the renter and their attorney. This was a bad outcome for everybody except legal services. The landlord settled for an enormous amount. And the renter faced eviction for a long time.

As an industry, it is very important to follow Chapter 93A scrupulously. We must always deal fairly and openly, and encourage other landlords to do so, as well. In this way, we will reduce the amount of settlement money flowing to those who advocate against us. And we will be supporting our mission to create better rental housing. No one wants to rent a place with chirping smoke detectors.