Mass. Coastal Real Estate is on Borrowed Time

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

It’s not too late to avoid the worst imaginable climate disaster, except perhaps for coastal real estate in Massachusetts. This is what may be inferred from the major international policy report published in August 2021, combined with maps being used by Realtor.com since 2020.

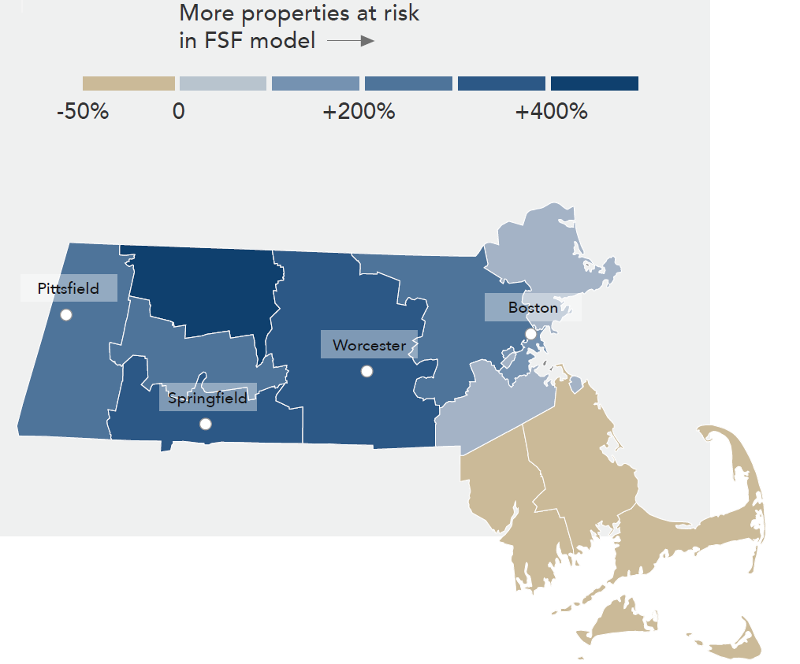

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) already publishes flood maps. Broadly, First Street Foundation maps agree on the Cape and Islands. First Street Foundation disagrees for coastal real estate in Boston and the North and South Shore. Editorial Use First Street Foundation https://firststreet.org/

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) now predicts with “high confidence” – the second highest level of confidence available – that coastal cities will be more likely to flood than they are today, considering the timeframe 2035 to 2065. This probability of flooding will further increase under all but the most aggressive (least likely) emissions reduction scenarios.

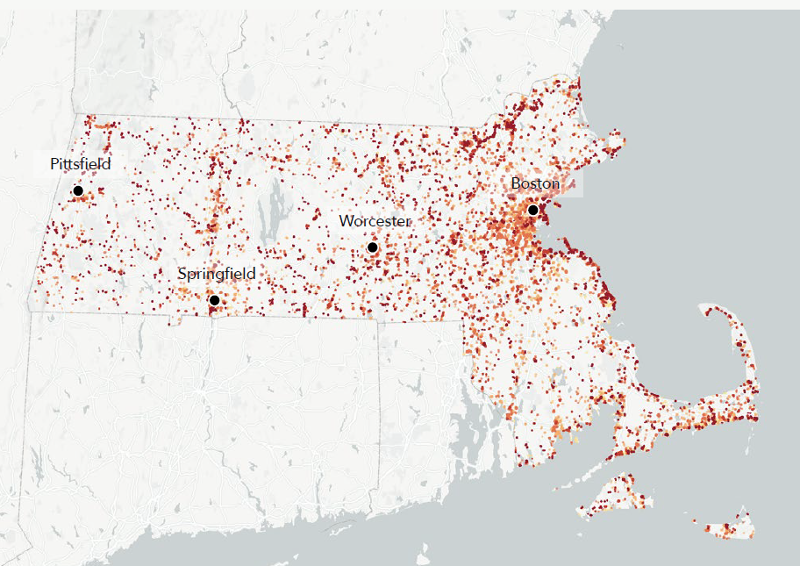

The absolute risk is already “major, severe or extreme” among Massachusetts properties deemed at risk. Realtor.com started publishing Flood Factor™ with its listings summer 2020. Their data comes from First Street Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit using IPCC estimates. First Street Foundation has identified 321,487 unique properties in Massachusetts with risk of flood from rain, river, tides and storm surge. Of these, Boston into South Shore and the Cape have near continuous zones of “severe” to “extreme” flood risk over the next 30 years.

These flood assessments disagree with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood maps commonly used for mortgages, except broadly speaking in the Cape and Islands. Overall, First Street Foundation, using the latest climate data, finds twice as many coastal properties as FEMA in the North and South Shore at risk.

(Since First Street Foundation also looks at rainwater floods, the difference with FEMA is marked for Franklin County, which has four times as many properties at risk as FEMA recognizes).

Note that Boston already floods 10 days a year.

Further coastal real estate flooding will be driven by rainwater and storm surge primarily, rather than baseline sea level rise.

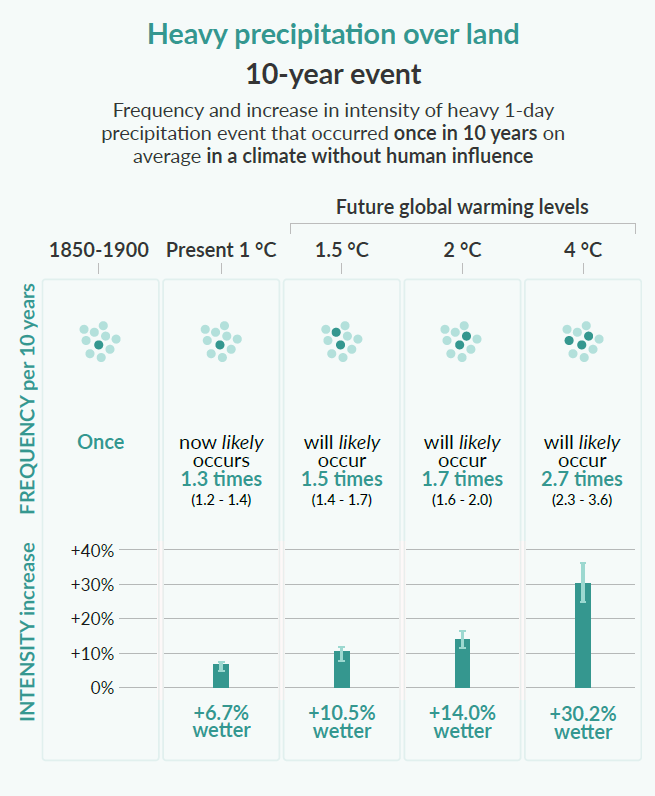

The IPCC report shows that rainfall over land increases in frequency and intensity in every possible climate future. If before the water used to just drain away before flooding, soon it will flood the property. Editorial Use IPCC.

How Has the Climate Already Changed for the Coast?

The IPCC report starts with the climate facts known from observation: we are heating the planet, and this is driving changes in our climate.

“A.1 It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.”

“B.2.2 With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes continue to become larger. For example, every additional 0.5°C of global warming causes clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, including heatwaves (very likely), and heavy precipitation (high confidence).”

The IPCC cites rainwater studies, which for most of Massachusetts real estate is the primary flood risk. The IPCC has high confidence that “the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased since the 1950s over most land area for which observational data are sufficient for trend analysis” (A.3.2). The trend is that heavy downpours will become more common.

Similarly, the IPCC cites studies measuring global mean sea level rise over time. Between 1901 and 1971, for instance, the sea was rising at between 0.6 to 2.1 mm per year (best estimate: 1.3 mm per year). That sounds small. But between 2006 and 2018, this rate has more than doubled to between 3.2 to 4.2 mm per year (best estimate: 3.7 mm per year). The IPCC has high confidence in these known sea level rises (A.1.7). This change has been “faster since 1900 than over any preceding century in at least the last 3000 years (high confidence)” (A.2.4). The trend is that the rate of sea level rise will further increase.

“C.2.7 Many regions are projected to experience an increase in the probability of compound events with higher global warming (high confidence).”

Overall, the ocean is higher, the waves are bigger and more frequent during storms, and the rain is falling faster than ever.

As of summer 2020, 321,487 individual Massachusetts properties have been identified by First Street Foundation and Realtor.com as having flood risk; this number is predicted to grow annually, and each property to have increasing risk. Hull: 65% of lots. Revere: 32% of lots. Boston: 19% of lots. Editorial Use First Street Foundation https://firststreet.org/

What Lies Over the Horizon for Coastal Real Estate?

With high confidence, the IPCC knows that all regions of the world except the landlocked ones will experience further rising sea level, more coastal flooding and more coastal erosion. These are three “climate impact drivers,” or CIDs, known to bear on Massachusetts.

The IPCC uses sophisticated modeling techniques to predict how the planet will change under various scenarios. Some scenarios include sharp curtailment of greenhouse gas emissions. Others assume we continue to install new fossil fuel equipment without regard to climate. The IPCC studies these models in approximately 50 global reference regions. Massachusetts is in a region that covers all of Eastern North America.

Eastern North America remains an area where outcomes are hard to predict compared to most of the rest of the world because our region is understudied. They call this “limited agreement,” not meaning that people disagree, but that the data for Massachusetts does not match data for New York or other parts of the ENA region, or is not detailed enough to produce trends.

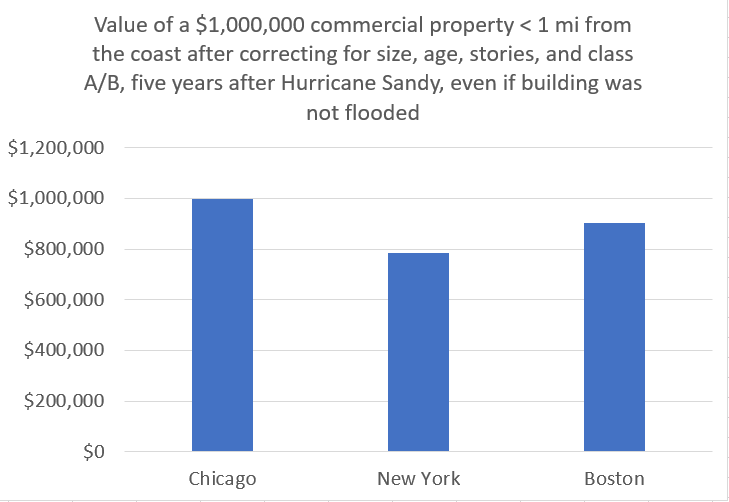

Addoum’s paper makes a purely mathematical observation. Coastal real estate tends to be more expensive, better developed, high quality, larger and newer, so in real life it tends to be more expensive. But after correcting for all of this, one finds coastal real estate has to work that much harder to offset its proximity to the ocean. CC BY-SA MassLandlords based on research by Addoum (any error our own).

How Much Value is Being Lost in Coastal Real Estate?

Not discussed in the IPCC report is our bottom line: real estate can lose value even if not directly flooded.

To date, loss of value in residential coastal real estate has been pretty mixed. It depends primarily on the sophistication of the next person in line to buy the property. As many of us know, owner-occupy home buyers tend not to be very sophisticated. This can make residential housing expensive and out of proportion to its value as an investment. Many of us have bought and sold coastal real estate without regard to flood risk.

Sophisticated investors, however, especially those who purchase larger properties and commercial real estate, are already pricing in flood risk. Lower prices offer higher rates of return for these riskier purchases.

Jawad Addoum of Cornell University and others published a 2021 paper in which they write, “residential property [is] largely held by uninformed households for the purpose of housing consumption [but] commercial real estate markets exhibit strong flood risk penalties.”

Addoum looked at the prices of commercial real estate in New York, Boston and Chicago after Hurricane Sandy. New York suffered long-term price decreases, even where properties did not flood, if they were close to the waterfront. Boston suffered fewer long-lasting and less severe price decreases because it was not directly impacted by Sandy, but it could have been. Chicago suffered no price penalties, as would be expected, because Chicago, even though it is a coastal city, is beyond the reach of the ocean.

“[O]ur estimates in New York suggest that a one mile increase in proximity to the coast results in 21.6% slower price appreciation among properties sold in the post-Sandy period. Meanwhile, our Boston estimates indicate 9.5% slower price appreciation following Sandy,” Addoum wrote.

Addoum corrected for building size, age, stories and class A vs class B. The writers looked at a period five years after Sandy. A coastal commercial property in New York that would be worth $1 million one mile inland was worth only $784,000 on the waterfront. In Boston, that same property would be worth more, $905,000, but still less than the same property inland.

Similarly, Serkan Catma in 2021 published an article looking at all condos and single-family homes sold between 2011 and 2016 in Hilton Head Island, a barrier island in Beaufort County, South Carolina. The county has lost 189 meters of shoreline due to erosion. “[P]roperties that are located within the zone of high, or very high, flood risk experience a 15.6% reduction in value.”

As properties flood with rain and storm surge, values will further decrease.

Hull, Mass is one of several communities with a majority of lots in “severe” flood risk, according to First Street Foundation. Visualization by floodmap.net for current sea level and a three-meter storm surge. https://www.floodmap.net/?ll=42.287596,-70.902585&z=13&e=1 Editorial Use FloodMap.net

Conclusion: How Should I Think About Flood Risk?

A 2018 article from WBUR, “Entrench or Retreat? That is the Question on Plum Island,” has the most salient summary of this. Mike Morris told Simón Rios, “at some point on these barrier beaches, somebody is going to be the last owner of the house that they're in.”

This means if you choose to purchase a beachfront, waterfront or otherwise coastal property, you need to evaluate that investment as if the residual value will be lower than when you buy it. The return on investment math should rely heavily or exclusively on net income, with relatively little, no or negative consideration for asset appreciation.

However hard it may be to predict the precise effects of climate change, your primary responsibility is to invest with margin of safety. Don’t overpay for coastal real estate.

The IPCC report is the August 7, 2021 “Summary for Policymakers” published as part of the “Climate Change 2021” report (Sixth Assessment) by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).