Limited Assistance Representation (LAR) for Landlords

By Peter Vickery, Esq.

This article covers limited assistance representation (LAR), a lesser-known form of legal assistance that may help some landlords contain legal costs. Pros and cons of LAR are discussed.

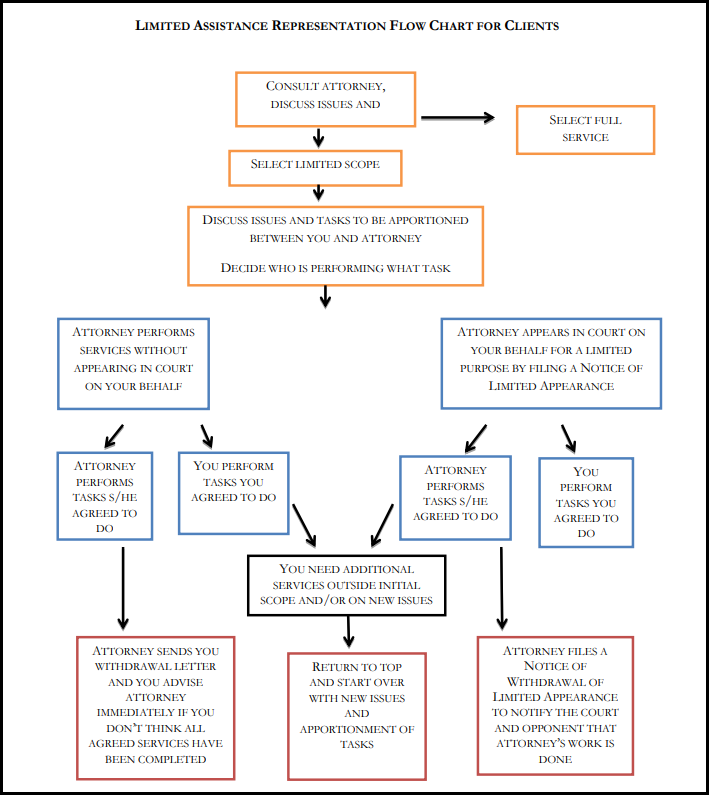

Buyer beware: 100% of the scenarios with Limited Assistance Representation end with the attorney leaving before the case is complete. (Flowchart from the Trial Court Training Manual).

Representation in Court

Some landlords worry that hiring a lawyer to evict a tenant is like writing a blank check, an open-ended commitment that could break the bank. It’s no secret that summary process cases can drag on and on (and on).

Corporations and LLCs have no choice: they have to hire attorneys. But landlords who are individuals have the pro se option, meaning they can represent themselves. Going that route certainly saves money, at least in the short-term. But housing law consists of several complex, overlapping state and federal statutes, some of them poorly drafted, plus a large body of case law, which combine to make it something of a specialized field.

To make matter worse, often the tenants will have access to publicly-funded or volunteer lawyers who know where to look for weaknesses in the landlord’s case. Some weaknesses prove fatal. Unsuspecting landlords may see their cases dismissed seemingly before they even started and leave the courthouse heads spinning, wondering what just happened.

Because there are so many traps for the unwary, representing yourself can prove a false economy. The expense of a lawyer versus the vagaries of the legal system presents a dilemma.

Pick-and-choose menu with LAR

Since 1998, the Massachusetts courts have been developing a third option between open-ended attorney commitments and self-representation: litigants in civil cases can hire lawyers for certain discrete tasks (e.g. writing documents, giving legal advice, and courtroom representation) instead of for the case in its entirety. The arrangement is à la carte rather than soup to nuts, and it is called Limited Assistance Representation (LAR). It has been available in the Housing Court since 2010.

Over the years, the rules governing LAR have expanded and evolved. The latest version is Trial Court Rule XVI, which allows limited assistance by LAR-qualified attorneys if “the limitation is reasonable under the circumstances and the client gives informed consent.” The lawyer has to give the client – and review with the client – a “written agreement that clearly and precisely states the scope of representation.” In addition to reviewing the written agreement before signature, the lawyer needs to obtain the client’s “informed consent.”

With a signed LAR agreement, the attorney is at liberty to file a limited appearance, which, like the fee agreement, includes a checklist of events: motion, hearing, ADR, trial, other court events, trial, and one titled “others (must specify).” Even without entering an appearance, which involves going on record as the attorney, a lawyer may help a client write a legal document (e.g. a motion or an opposition to a tenant’s motion) so long as the document contains the phrase “prepared with assistance of counsel.” With that formula of words in place, the client may lawfully sign the document, even though the actual author is the attorney.

A non-exhaustive list of LAR-qualified attorneys who practice in the Housing Court is available online.

LAR offers a win-win. Landlords of moderate means are able to hire well-trained attorneys who specialize in the field of landlord-tenant law, while retaining control over the billable hours. The lawyers have access to clients who would otherwise not be in the market for their services. So what’s not to like?

Self-service versus self-serving

One drawback of LAR from the lawyer’s point of view is the possibility that the client will forget or ignore the limited scope of the representation. Lawyers have a duty to zealously advocate for their clients and find it hard to draw the line, even when the line is apparent on the face of the fee agreement. But more prevalent than the fear of the overly-demanding client is the fear of the confused client who knows that the line exists but cannot quite locate it. And confusion bedevils attempts to draw lines around legal services.

The official LAR Training Manual contains four sample fee agreements with the à la carte menu, i.e. the checklist of particular services. For each service there is a box for a “Yes” (meaning the attorneys will perform the service) or a “No” (meaning the clients will serve themselves).

By its very nature, the concept of LAR suggests that the clients will represent themselves with only limited assistance from counsel. Self-representation is the default setting. In that context, clients may believe that they should not check every box on the checklist. After all, if you write “Yes” in every box, the assistance is not really limited. Hence the temptation to write “No” in some boxes, thereby reserving that service to the client. Unfortunately, the differences between the services are not all intuitive, obvious, or even (in some instances) comprehensible.

For example, in Fee Agreement Version #2 the entry for service B is “information about document preparation” and the entry for service C is “assistance with document preparation.” Listing these services separately implies a distinction between the two. But where does informing end and assistance begin? The question seems well suited for a graduate seminar on the philosophy of language.

Similarly, the first service on the list, category A, consists of “advice about law and strategy related to an ongoing mediation, negotiation, or litigation,” while the service listed further down as N is “assistance with substantive legal argument.” Discerning the difference between legal and strategic advice vis-à-vis assisting with substantive legal argument could keep those philosophy-of-language grad students busy for hours, even days. Can a lawyer provide one without the other, i.e. assist with substantive legal argument without providing advice about law?

At least Fee Agreement Version #2 only has categories A-O. The list in Version #3 runs from A to U.

In addition to the blurriness of the categories, there is the matter of price. Naturally, the pricier aspects of the case are the ones that some people would prefer to handle themselves on a self-service basis. But the price (the legal fee) tends to reflect the degree of complexity. The greater the complexity, the greater the number of billable hours it will take to research and prepare the written argument, and the higher the price.

Leaving the costlier parts of the case to the client exposes the attorney to risk. The attorney needs to explain that those features will be complex, but the client – not having been to law school, passed the bar, and practiced law – cannot possibly know how complex.

They know that they don’t know something, but they don’t know exactly what that something is. They confront “known unknowns” in the words of former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

Clients face the temptation to express agreement without truly appreciating the implications: they would be hiring a lawyer for the relatively easy tasks but assuming responsibility for the most challenging parts themselves. But if the lawyer urges the client to write “Yes” in most boxes, it looks self-serving. Mindful of this phenomenon, some lawyers will perform – or believe that they should perform – all the services, even those that the clients have reserved to themselves. Why?

Among the “Top 10” cold-sweat nightmares of the LAR attorney: the one where the Board of Bar Overseers concludes that the lawyer’s decision to leave the challenging parts of the case to the client was not – despite the client’s written agreement – reasonable, and that the client’s signature on the LAR agreement did not reflect informed consent. The LAR attorney would in that case be up a creek without a paddle, obligated to advocate for the owner who has already indicated that they cannot afford those services.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges inherent to limited assistance representation and the shortcomings of the official forms, there are competent, zealous advocates who are willing to represent landlords on a limited-assistance basis. Demand may exceed supply, but in time more attorneys will likely step forward. If clients and lawyers alike enter into LAR agreements with their eyes open, justice may emerge.

The MassLandlords Helpline can be purchased as hourly or prepaid bundles of help.