How Much Are Your Massachusetts Property Taxes?

| . Posted in News - 3 Comments

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

Massachusetts property taxes are among the highest in the nation. They often make a sizable impact on landlords’ bottom lines, chipping revenue down to unsustainable levels or even forcing some to exit the industry.

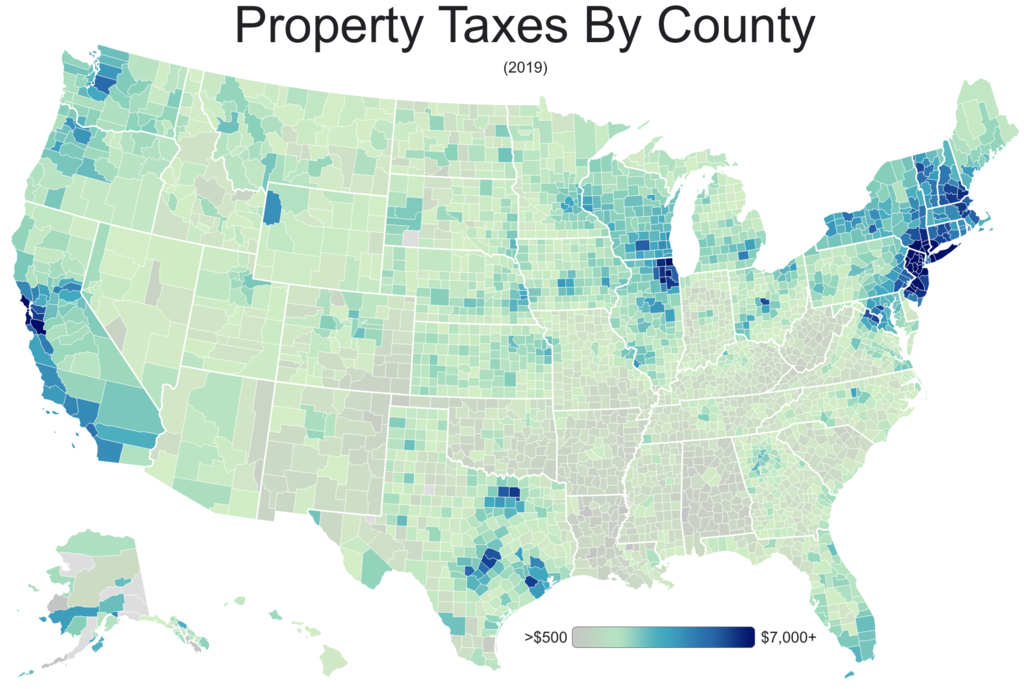

Property taxes vary vastly between states and municipalities across the nation, as illustrated by this map, ranging from $500 per year to more than $7,000. Image: cc by-sa Wikimedia

Very few people enjoy paying property taxes (or any taxes for that matter). Massachusetts has the fifth-highest median residential property tax rate ($4,309 per year) in the nation, trailing New Jersey, Connecticut, New Hampshire and New York.

Recent surges in property tax across the state don’t help. The combination of increased home values in recent years and inflated municipal budgets are prompting many towns and cities to bump up property tax rates and assess higher values on properties.

Housing providers manage property tax increases in different ways. Many raise tenants’ rent to offset their higher assessments. Some cut back on or defer needed improvements or repairs of rental units and buildings. Others appeal their assessments with each increase and attempt to negotiate with their local government to lower what they owe. And a percentage throw up their hands, unable to absorb more tax hikes, and leave the landlording industry altogether, selling their rental properties for what they can.

The Inn on Washington Square, a once-historic bed and breakfast facing Washington Square Park in midtown Salem, Mass., with a relatively high tax levy, has been refashioned into three condominiums. Image: editorial use google maps

Unsustainable Property Tax Increases

Bobby Marcey is an example of the latter. He’s the former owner of the Inn on Washington Square, a historic, thriving (and haunted?) bed and breakfast in Salem, Mass. Marcey operated his three-room inn from 2006 to 2013, located two blocks down from the Salem Witch Museum, facing Washington Square, a midtown park.

In the seven years he owned the inn, Marcey’s residential property taxes skyrocketed from about $3,000 to nearly $15,000 a year, he said, sometimes increasing by $2,000 to $3,000 from one fiscal year to the next.

“I didn’t mind the taxes in Salem in the first couple years I owned it,” Marcey recently told MassLandlords, “until they really hit me” with annual high-percentage increases. In discussions with Salem Mayor Kim Driscoll, Marcey recalled, he was told he was being assessed with a “view tax” due to the proximity to a popular park within eyeshot.

A view tax is not an actual separate tax, rather it’s a term used for part of a municipality’s property tax assessment. Properties with a view have higher value and are therefore assessed at a higher amount than similar or nearby properties without a view.

Marcey struggled to hang on to the inn for a couple years. He sought permission from the city to add another rentable room to offset the increasing tax burden but was told he could not due to the building’s historic status.

Finally, heartbroken and unable to sustain the high tax burden, Marcey sold the building to a condominium developer. The once-renowned inn now accommodates three condos.

Marcey currently owns and operates the Libby House, a bed and breakfast in Gorham, N.H., where, ironically, he is surrounded by majestic mountains but pays no “view tax” as part of his $2,000-per-year property tax levy.

Managing High Property Taxes

Operating a bed and breakfast inn is different from leasing dwelling units, but when it comes to property taxes, housing providers share similar stories to Marcey’s about struggling to manage increasing levies.

MassLandlords member Alex Narinsky owns rental properties in Cambridge, Newton and Somerville. His property tax rate has increased precipitously over the past two years, he said, among the three municipalities.

“The property taxes are very high in Massachusetts,” he said. “Moreover, they are constantly increasing. The assessed value is constantly up.”

Narinsky raised rents on his long-term tenants, he explained, to partly offset property tax increases. “I am uneasy to increase the rent for good-paying tenants by more than 3%, so this increase did not fully offset the increase in property taxes and maintenance expenses. This year I will need to increase more. This will probably disappoint long-term tenants.”

What Are Property Taxes?

Property taxes are a complicated issue. Few owners enjoy paying them, even if they recognize their necessity. Property taxes are an annual fee levied on the assessed market value of every property within a community – residential, commercial, industrial and open space. Towns and cities use revenue from property taxes (along with state aid and other funding sources) to pay for local schools and services such as public transportation, public safety, snow removal, libraries and parks. In fiscal year 2020, Massachusetts communities paid for 66.4% of local services with property tax revenue. State aid covered 11.3% of municipal budgets statewide. These percentages vary widely among individual communities.

Massachusetts towns and cities base real estate valuations on “full and fair cash value,” that is, how much a willing buyer would pay a willing seller for a property on the open market. Residential properties are assessed in part according to the market sale amounts of comparable properties (“comps”) within proximity of the property being assessed. Commercial property assessments consider land and property value as well, but also use a formula that evaluates income generated by a business or businesses on the property.

Residential vs. Commercial Property

In Massachusetts, rental businesses may be taxed at different rates depending on the number of units. Small rental businesses of up to three units tend to be taxed using a residential classification. Rental businesses of four units or more, including rooming houses, are often taxed at commercial rates. Most Massachusetts communities employ the same rate, or a single rate, for both residential and commercial property tax valuations. However, some – mostly larger municipalities – use split rates, levying a higher percentage for commercial property tax liens.

Commercial property tax rates are often considerably higher than residential rates. For that reason, some housing providers, like Bobby Marcey in Salem, intentionally keep their rental businesses at three rooms to avoid paying commercial tax rates.

In some communities, the jump from residential to commercial would mean paying twice as much in property tax. In Andover, for example, an owner of a two-unit rental would pay a residential rate of $14.6 per $1,000 of assessed value, while a five-unit owner would pay a commercial rate of $29.29/$1,000. In Worcester, the difference is $15.21/$1,000 residential vs. $33.33/$1,000 commercial.

Property Tax Comparisons

Property owners in all 50 states pay property taxes. New Jersey has the highest residential rate, averaging 2.49% and an annual payment of $8,362. States with the lowest residential property tax rates are Hawaii, Alabama, Colorado, Louisiana and South Carolina. However, the rate of taxation and the actual amount of taxes levied on properties vary widely from state to state and municipality to municipality within each state.

Massachusetts communities that pay the highest effective property tax rates are Longmeadow ($24.64 per $1,000), Wendell ($23.24/$1,000) and Greenfield ($22.32/$1,000). Municipalities with the lowest effective rates are Chilmark ($2.82/$1,000), Hancock ($3/$1,000) and Edgartown ($3.03/$1,000). All six of these communities employ a single tax rate for residential and commercial property assessments.

Calculating property tax rates and comparisons can be misleading. What owners pay in property tax is a combination of the local tax rate and the assessed value of their property. While Hawaii enjoys the lowest average residential tax rate in the nation, 0.28%, its home values are the highest in the nation, with a median home value of more than $848,000 in 2022. Therefore, Hawaii residents pay more property taxes than residents of some other states.

In Massachusetts, the owner of a home worth $500,000 in Longmeadow would pay residential property tax of $12,320 per year. In Chilmark, a small town on the outer banks of Martha’s Vineyard, the same house would yield $1,410 in residential property tax, an annual tax difference of $10,910 for the same house.

Let’s look at a commercial rate comparison. An owner of a six-unit apartment building in Worcester valued at $1 million would pay upwards of $33,000 ($33.33/$1,000) in taxes. In Tewksbury, the same property would cost about $27,000 ($27.25/$1,000) in annual property taxes. By comparison, across the state, the owner of a three-unit multifamily in Springfield valued at $1 million would pay $18,000 ($18.82/$1,000) in annual residential property taxes.

How Massachusetts Compares

That said, it remains that Massachusetts property owners pay a disproportionate amount of property taxes relative to owners of real estate in other states. And for those renting out residences and juggling the multiple costs associated with landlording, ever-increasing property taxes can make or break the business.

The average property tax rate itself isn’t particularly high in Massachusetts. Across all Massachusetts municipalities, the average property tax rate equals 1.23%, which ranks the state 18th in the nation, well below New Jersey’s average. The national average is 1.10%.

It’s the high market values of real estate in Massachusetts that push the state toward the top of the list in property taxes. Massachusetts home values hit a high-water mark in 2021, topping out at $750,000 for an average single-family, up 10.5% from 2020. The higher market value your home has, the more you will pay in residential property tax.

It’s possible that Massachusetts home values will come down slightly as federal interest rates increase to fight inflation, and that property taxes for some could descend with values. But Massachusetts struggles with an overall shortage of housing, and significant declines in home values seem unlikely any time soon.

Appealing Real Estate Tax Assessments

Part of property owners’ frustrations with the tax they pay on real estate is the seeming subjectivity within the assessment process. Assessors base their valuations on market forces and study and compare real estate activity around their communities’ neighborhoods to determine what owners should pay in tax. Assessors are required to submit their valuations every five years to the state Department of Revenue for certification.

But they don’t always get it right. In Worcester, a coalition called AWARE (Accurate Worcester Assessments on Real Estate), headed by Joan Crowell, brought about an in-depth review of the city’s assessment process by the state Department of Revenue after pointing out unusually high tax levies on some properties.

Part of property valuations are determined by the amount of money a municipality needs to raise to pay for schools and local public services. This levy is determined by Town Meeting or a select board. In Massachusetts, municipalities are limited by Proposition 2 ½, a law that restricts the overall increase a town or city can collect in property taxes, to 2.5%, from one year to the next. (Proposition 2 ½ is a restriction on a municipality’s total property tax revenue; tax increases on individual properties are not restricted to that percentage and may exceed 2.5%.)

Proposition 2 ½ can be, and often is, overridden by community referendum, for one-time capital projects, for example, construction of a new school or healthcare facility. Also, the Community Preservation Act, an option that allows municipalities to raise funds to preserve open and outdoor spaces and build affordable housing, may override Proposition 2 ½, again by referendum.

Property owners who disagree with their valuations are legally allowed to appeal tax assessments by filing an abatement with the town tax office. An abatement is essentially a request to reduce the assessment and pay a lower property tax bill, or receive a refund.

A number of exemptions are also available, respective to each municipality, that allow some property owners to pay less in taxes. For example, surviving spouses of firefighters or police officers are often allowed property tax exemptions. Other exemptions might include people experiencing hardship due to age, poverty or infirmity. Check with your community’s tax office to learn about local property tax exemptions.

The Cost of Quality Living

Part of the reason Massachusetts residents pay a relatively high amount in property taxes is because we live in a desirable location.

By most accounts, Massachusetts is a good place to live, evidenced by several metrics. Research firm TOP Data recently deemed Massachusetts residents the happiest people in the country based on factors like relatively high income, longer-lasting marriages than other states and favorable social policies. WalletHub named Massachusetts the best place to live in the U.S., eyeing metrics such as affordability, economy, education, health, quality of life and safety. And Massachusetts has long been among the healthiest states in the U.S.

Many of the aspects that make Massachusetts a desirable place to live – e.g., high-quality schools, smooth roads and streets, safety and security – cost money and are supported by property tax. Schools across the state rank among the best in the nation. Many of our towns and cities maintain ample green spaces, parks and nature preserves for our outdoor enjoyment. Our access to healthcare is at the top of the list. And violent crime in Massachusetts cities consistently ranks lower than other states.

Still, great place to live or not, Massachusetts landlords must contend with property taxes that can threaten their businesses’ profitability and solvency. For those like Bobby Marcey and Alex Narinsky, the tax burden is inordinately high.

The quest to bring about tax policies that are fair and reasonable for landlords and other property owners is a long-term one. It’s tied to issues like zoning, new housing and balance among residential and commercial property owners. These are issues that animate MassLandlords’ energies and focus.

If you want to assist the ongoing campaign to enact smarter, more equitable policies that result in fairer property taxes for housing providers, consider donating a 10% equivalent of your property tax bill to MassLandlords’ Property Rights Supporter Program.