Choosing Judges in Massachusetts: The Governor’s Council and Judicial Nominating Commission Then and Now

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

By Peter Vickery, Legislative Affairs Counsel

How does somebody become a Massachusetts judge? Landlords ask this question from time to time, often after a trip to Housing Court. The answer: It depends on the type of judgeship.

John Adams five years after his constitution was adopted by Massachusetts voters, age 50. Portrait by Mather Brown.

Anyone who followed the news during the contentious Kavanaugh hearings knows that the President’s nominees for the Supreme Court, and other federal courts, can only be appointed with the advice and consent of the United States Senate.

Readers may be surprised to learn that at the state level, Senators used to perform the same advice-and-consent function here in Massachusetts. The original State Constitution, written by John Adams and adopted by the people in 1780, gave the power to approve or veto the Governor’s choice of judges to a group of State Senators.

The Original John Adams Design: Advice and Consent

Back then, the Governor’s Council was a subset of the Senate, with all senatorial candidates running for the office of “Counsellor and Senator.” The winners convened together with the newly-elected State Representatives – all “assembled in one room,” as John Adams (ever attentive to detail) provided – to choose nine of their number to serve double-duty as Senators and Governor’s Councilors.

The original intent, therefore, was that the Governor would nominate the judge and a select group of Senators would confirm or veto that nominee.

Direct Election Sweep

The John Adams design changed in 1855 when the voters ratified a constitutional amendment that separated the Governor’s Council from the Senate. The switch to direct-election was one of 10 constitutional amendments that the voters approved between 1855 and 1859.

During this period Bay Staters made a range of offices directly-elected, including secretary of the Commonwealth, attorney general, treasurer, auditor, sheriffs, registers of probate, and district attorneys. They also did away with the rule that in order to win an election a candidate needed a majority of the votes; since then, a mere plurality has been sufficient.

In 1857, the voters approved an amendment making the ability to read English a condition for registering to vote. Two years later, they imposed a requirement that foreign-born citizens had to live in the United States for at least two years after naturalization before being allowed to hold public office.

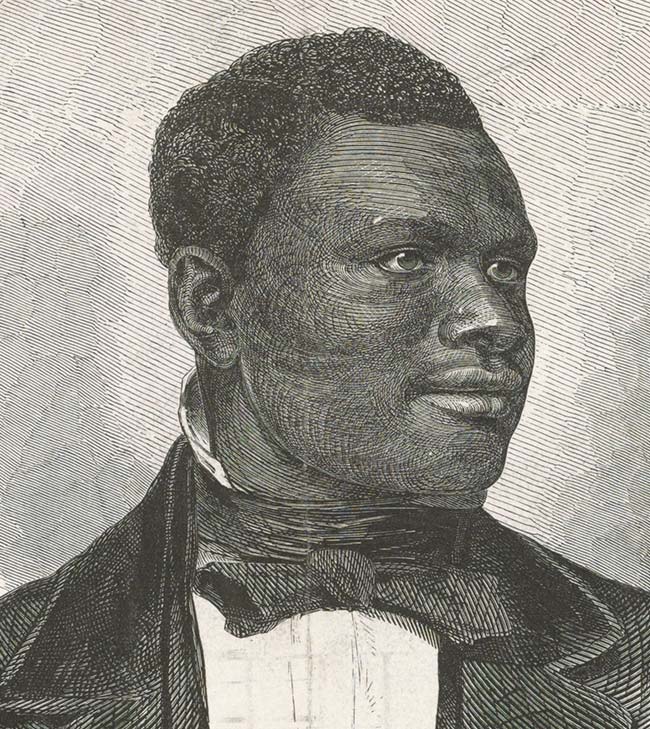

Anthony Burns, the man whose escape from slavery and forced return precipitated creation of the Massachusetts Governor's Council.

A New “Know Nothing” Party

This slew of changes followed the Constitutional Convention of 1853 and the spectacular general election of 1854 in which the American Party, commonly known as the Know Nothing Party, swept the board.

The Know Nothing Party campaigned against immigration, and it had a pronounced anti-Catholic bent. Its Know Nothing moniker arose from the party’s secrecy oath, which required members to respond to inquiries from outsiders with a Sergeant Schultz-like “I know nothing.” The nickname did not hold them back. When the Massachusetts Legislature convened in 1855, every seat in the Senate was held by a Know Nothing, as were all but three seats in the House of Representatives.

A focal point for the Constitutional Convention of 1853 was the issue of Massachusetts judges helping enforce the federal Fugitive Slave Act. The cases of two men who had escaped slavery and settled in Massachusetts – Thomas Sims and Shadrach Minkins – became rallying points for abolitionists. Despite the fact that slavery had been illegal in Massachusetts since the 1780s, Massachusetts judges applied the federal law. Massachusetts abolitionists vowed to change this.

On the theory that electoral accountability would persuade judges to refrain from enforcing the federal Fugitive Slave Act, the abolitionists pushed their fellow constitutional convention delegates to recommend an elected judiciary. They succeeded. The proposal that Massachusetts judges should be elected was part of the package that the Constitutional Convention presented to the voters in the form of a brand-new Constitution. But in the general election of November 1853, the voters rejected it.

The following year, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Virginia and made his way to Massachusetts. In a replay of the Thomas Sims and Shadrach Minkins cases, Suffolk County judge Edward Greely Loring, who also held the office of federal circuit-court commissioner, sent Burns back to Virginia. The upsurge in anti-slavery feeling had a dramatic impact at the polls: the Democrats and Whigs were washed away in the Know Nothing tide.

The Know Nothing legislators tried but initially failed to remove Loring from the bench. But they put another direct-election proposal on the ballot in 1855, and this time it passed. The Governor’s Council was born. It would be directly elected and directly responsible for confirming judgeships. (Loring was removed in 1857.)

Unpardonable Governor’s Council Corruption

Between 1855 and 1964, the Governor’s Council accumulated a range of statutory powers and a reputation as den of patronage and corruption. Among the scandals that swirled around the Council was one that involved Councilor Daniel H. Coakley, who had been disbarred in 1922 for, among other things, extortion. Coakley was a former campaign manager for John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald and occasional ally/sometime rival of James Michael Curley. The little matter of disbarment did not outweigh Coakley’s connections. He was elected to the Governor’s Council in 1932.

In 1938 Coakley presented a pardon petition to Governor Charles “Chowderhead” Hurley. Hurley signed it. The beneficiary of the pardon? A young man from Worcester who had been sentenced to five years as an accessory to murder. His name? Raymond Patriarca, a rising star of the New England mafia. Among the letters of support that Coakley had offered in support of the request for a pardon was one from a priest, Father Brambilla of East Boston, whose signature had been obtained by fraud. Another letter of support was from a Father Fagen of Providence, Rhode Island, who did not exist at all.

In 1941, the House voted to impeach Coakley and the Senate removed him from office. The selling of pardons and other favors continued, however. Finally, in 1964, in an attempt to put an end to these perennial scandals, the voters approved a ballot measure that stripped the Governor’s Council of its statutory powers. But the Council’s constitutional authority remained intact, including its role in approving judges.

Governor Dukakis one year after he formalized the Judicial Nominating Commission.

Judicial Nominating Commission

From the 1960s onward, Massachusetts governors have set up advisory bodies to receive applications and conduct interviews independently of the Governor’s Council. In 1975 Governor Michael Dukakis made the process more formal and issued an executive order establishing what he called the Judicial Nominating Commission.

Sensing a threat to its prestige (and patronage), the Governor’s Council, led by longtime Councilor Patrick J. “Sonny” McDonough, pushed back. The Councilors asked the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) for an advisory opinion as to whether Governor Michael Dukakis had impermissibly delegated his constitutional authority – and that of the Council – to an unelected body. Because the commission’s role was merely advisory, the SJC ruled in favor of Dukakis. The JNC would stand.

Since then, all governors have issued executive orders of the Dukakis kind to create a Judicial Nominating Commission. In keeping with tradition, early in 2015 Governor Baker issued Executive Order 558, which established the current 21-member Judicial Nominating Commission.

How the Judicial Nominating Commission Works

The JNC posts vacancies online and publicizes them via the local bar associations. After an initial blind review of applications, with the names of the applicants redacted, the JNC chooses a group of candidates to interview. Applicants meet with a panel of JNC members and, if successful, move on to an interview with the whole commission. Then the JNC sends a list of names to the Governor’s Chief Legal Counsel, who seeks opinions from the Joint Bar Committee on Judicial Appointments, which consists of 24 attorneys from the various bar associations across the Commonwealth.

After reviewing the Joint Bar Committee’s report, the Governor decides whether to nominate a candidate. If he does, the nomination goes to the Governor’s Council.

How the Governor’s Council Works

Depending on the nature of the political relationships in play, the Chief Legal Counsel may choose to confer with the Governor’s Councilor from the nominee’s district to try to ensure a smooth confirmation process.

There is no constitutional requirement that the eight-member Governor’s Council hold a hearing, but it has become standard practice. Most hearings are held in the State House but sometimes they take place in the Governor’s Councilor’s district.

Hearings of the Governor’s Council usually last one or two hours and, not being televised, are rarely as acrimonious as Senate confirmation hearings. Friends, relations, colleagues, and area legislators testify to the nominee’s virtues. Councilors from other districts state that the nominee’s own Councilor speaks of the nominee very highly, which is all they need to know. It is all quite convivial and collegial, so much so that one former Governor’s Councilor has likened the experience to the old TV show This is Your Life. The week after the hearing, the Council votes.

Conclusions about How Massachusetts Judges are Chosen

The original intent was that Senators should have an “advice and consent” role.

After 1780, the history of the judicial-nomination process in Massachusetts became strangely entangled with that of slavery and anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic bias and direct election fervor. This resulted in the Governor’s Council.

After 1975, a dose of anti-corruption, good-government sentiment was mixed in, resulting in the Judicial Nominating Commission.

The final say in the Governor’s choice of judges today remains vested in a Governor’s Council. Sadly, this body boasts a staggering track record of cronyism and corruption.

In sum, the process for selecting Massachusetts judges and the history of its development would likely have left John Adams incredulous. At least, the next time you prepare for Housing Court, remember it’s not as bad as it used to be.