Landlords in Mass. Sued for Discrimination Following Watchdog Sting Operation

By Kimberly Rau, MassLandlords, Inc.

Nearly two dozen housing providers are in hot water after a sting operation from the national housing rights group Housing Rights Initiative revealed that they had denied individuals a tenancy based on their source of income, a protected class in Massachusetts.

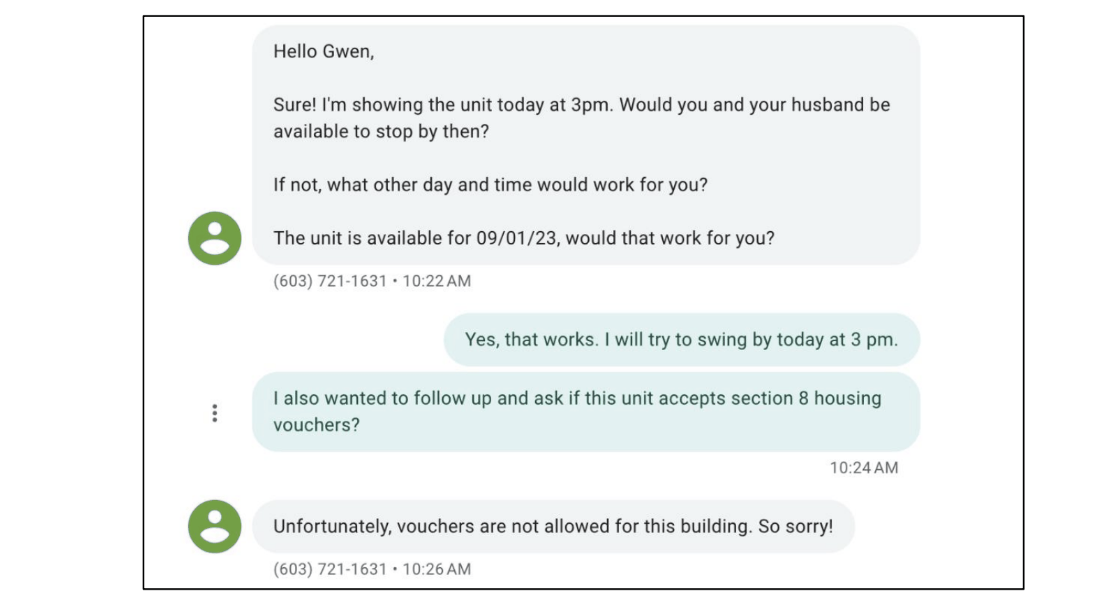

After confirming the rental unit was available and offering an appointment to see it in person, a representative of Charlesgate Realty Group violated fair housing regulations by telling the applicant Section 8 was not allowed for the property. (Image: fair use)

This lawsuit should serve as a reminder that it is important to know and comply with all housing anti-discrimination laws. You never know why someone is asking you the questions they are.

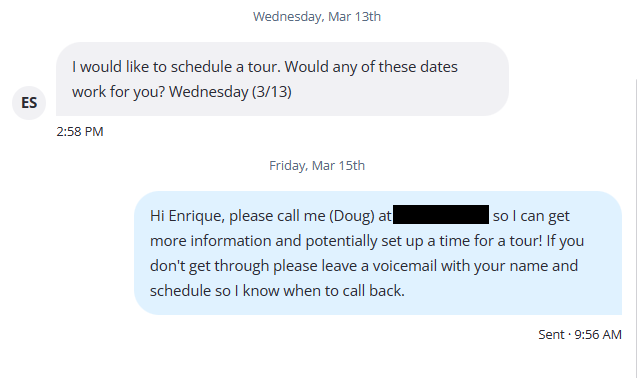

This Zillow message, from a prospective tenant to our Executive Director Doug Quatrocchi, shows an example of lawful communication about a rental property. Hint: Don’t tell people you don’t take Section 8. [Image: CC by SA 4.0 MassLandlords, Inc.]

HRI v. Charlesgate et al

In early 2023, people contacted individual landlords and realty groups to inquire about properties that were listed for rent on various rental websites. Once they confirmed the property in question was still available, the individuals informed the landlord or property manager that they had a Section 8 voucher. Twenty of those conversations allegedly led to denials because the purported applicants had a federal housing subsidy.

But these individuals weren’t actually interested in renting an apartment. They were trying to see if landlords were complying with laws in Massachusetts that prevent landlords from denying tenancies based on source of income. This includes people who receive Section 8 or other housing vouchers. When the testers reported their findings back to Housing Rights Initiative (HRI), the group filed a lawsuit against the individuals and companies behind the denials.

The lawsuit was filed in Suffolk County Superior Court on Feb. 21, 2023. HRI has called it the largest fair housing lawsuit by defendant size to date in Massachusetts.

The full court document details many of those conversations. Screen shots of messages begin on page 21. The ones we reference appear to be from the messaging platform offered through Zillow, a third-party real estate marketing company used by some of the housing providers mentioned in the lawsuit.

“Hi Ia,” one tester wrote to Ia Iarajuli, a broker from Harvard Ave. Realty. “This is Noelle. We spoke about #1A at Browne St.? I wanted to clarify if I could use my Section 8 voucher at this property.”

“No I’m sorry,” Iarajuli replied. At the time of the conversation, the company was representing the owner of the property, Evelyn Saleh.

Another conversation reportedly happened between a tester and broker Mario Fiume, who was representing Anzalone Realty. Anzalone Realty was brokering a Boston apartment owned by Filippo Frattaroli. The applicant asked about Section 8, at which point Fiume told them he would have to ask the owner. The response Fiume came back with was short:

“No Section 8 I am sorry.”

Fines for violating the Fair Housing Act can be up to $50,000 (third offense) for each offense, plus attorneys’ fees. (This lawsuit also asks for attorneys’ fees, though the testing was reportedly grant-funded.)

Is It Legal to Pretend to Be Someone You Aren’t?

Testing landlords to see if they’ll violate the Fair Housing Act is nothing new in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) regularly sends out testers, and litigates thousands of discrimination cases every year. Occasionally, people question this: How is it legal to pretend to be someone you aren’t to get information, and then file a lawsuit based on that premise?

The precedent allowing such testing goes back to a 1982 U.S. Supreme Court case, Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman. The catalyst for the case happened when representatives of the Havens Realty Corp., of Richmond, Va., allegedly told a Black tester from the nonprofit Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME) that no apartments were available in a particular complex. The company then allegedly told a white tester from HOME that there were apartments available.

The court found that the Black tester, known by their last name, Coleman, had the right to sue. It cited section 804 of the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination when selling or renting properties.

“Section 804(d) establishes an enforceable right of "any person" to truthful information concerning the availability of housing. A tester who has been the object of a misrepresentation made unlawful under § 804(d) has suffered injury in precisely the form the statute was intended to guard against, and therefore has standing to maintain a damages claim under the Act,” the Supreme Court decision reads.

In other words, it didn’t matter that Coleman had no intention of actually renting the apartment they were asking about. They were told that the apartment was unavailable. However, when a white tester applied, they were reportedly told it was available. That’s where the violation occurred.

"That the tester may have approached the real estate agent fully expecting that he would receive false information, and without any intention of buying or renting a home, does not negate the fact of injury within the meaning of § 804(d),” the decision reads.

In fact, court precedent allowing for discrimination testing goes back even farther. In the 1973 decision for Hamilton v. Miller, the United States 10th Court of Appeals defended the practice, saying:

“The trial court was critical of the conduct of University officials, characterizing it as acting ‘under false pretenses’, not in ‘good faith’ and done for the purpose of ‘framing a law suit’. We give no comfort to such criticism. While actions intended to found a law suit are not favored they at times must be tolerated. …It would be difficult indeed to prove discrimination in housing without this means of gathering evidence.”

Isn’t Discrimination Testing a Form of Entrapment?

If you are a landlord who denies a tenant based on having Section 8, you are not likely to win in court on the grounds that you were entrapped.

State documents on entrapment state “[a] person is entrapped if law enforcement officials, either directly or through an agent, induced a person to commit a crime which they would not otherwise have committed.”

First, discrimination infractions are civil violations, not criminal, which is an important distinction. Entrapment is a defense for criminal charges.

Then, setting aside the fact that Housing Rights Initiative is not a law enforcement group, and was not acting on orders from a law enforcement group, the landlords in the lawsuit do not appear to have been forced to deny housing to anyone. Court documents show landlords and property managers denying tenancies upon merely being asked if Section 8 would be a problem.

“A request by law enforcement officials for the defendant to engage in criminal activity, standing alone, is not sufficient evidence of entrapment,” the document continues. It also states that “undercover methods” may be used by law enforcement, as long as they “merely afford opportunities for the commission of the offense by one ready and willing to commit it.”

In other words, being asked if you take Section 8 is not entrapment. Also, tangentially, undercover police officers are allowed to lie and pretend they aren’t police officers, and they don’t have to tell you the truth if you ask. The idea that it’s entrapment if you ask a cop if they’re a cop and they lie is a myth.

Don’t Find Yourself at the Center of a Fair Housing Discrimination Lawsuit

Fortunately, it’s easy to avoid being sued for discrimination based on source of income/subsidy: Just don’t do it.

If an applicant asks you if you take Section 8, or a state housing subsidy voucher, your answer in Massachusetts must be “yes.”

This doesn’t mean you absolutely have to take anyone with a housing voucher who wants to rent your place. It does mean you should screen them exactly as you would screen someone who does not have a subsidy.

If the tenant has a large dog for a pet (not an emotional support or service animal) and you don’t allow pets, you don’t have to make an exception because they have Section 8. If the applicant smokes, and your property is non-smoking, you can deny them for that reason. Smoking is not a protected class.

But if the applicant passes your screening, denying them simply because you don’t want to get involved with housing vouchers would be wrong, unlawful, and potentially very expensive for you.

Conclusion

Discrimination testing has a long history in Massachusetts. With court precedent to fall back on, agencies that conduct testing aren’t likely to stop any time soon.

It would be interesting to see how a court would handle a challenge to this precedent, but as far as we know, no one has tried in recent years.

Regardless, there’s no room for discrimination in your housing practices. Don’t be caught violating the Fair Housing Act with testers or legitimate applicants. If you are unfamiliar with all of Massachusetts’ protected classes, we recommend you visit our discrimination page and review the standards for providing fair access to housing for all.