Widely Used Refrigerant Completing Phaseout for Commercial, Industrial

. Posted in News - 7 Comments

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

As of Jan. 1, 2024, the refrigerant R-410A, a common type of refrigerant used in commercial and industrial cooling equipment (as well as residential heat pumps and air conditioners) can no longer be sold, installed or manufactured for commercial and industrial use in Massachusetts.

There are thousands of different types of refrigerants, from ammonia to Freon, sulphur dioxide to propane, and a long list of commonly used refrigerant chemicals assigned ‘R’ numbers by ASHRAE (the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Engineers). Image: cc by-sa Wikimedia commons.

Residential use is not included in this phaseout, for now. But this prohibition of R-410A begs the question: when will this pollutive refrigerant, and others, be banned for residential use as well?

R-410A is a hydrofluorocarbon (HFC). Along with other HFCs, its use is being phased out for some end uses in most of the world because these chemicals are greenhouse gases, which trap heat within the earth’s atmosphere. Their presence in the atmosphere contributes heavily to global warming. In fact, for scale reference, these chemicals have up to 10,000 times more potential to trap heat than car exhaust.

Residential consumers who currently own equipment using environmentally harmful HFCs, like R-410A, are not required to replace it or stop using it as part of this phaseout. But, for the sake of the environment, any new purchases of cooling or HVAC equipment should be outfitted for lower impact refrigerants.

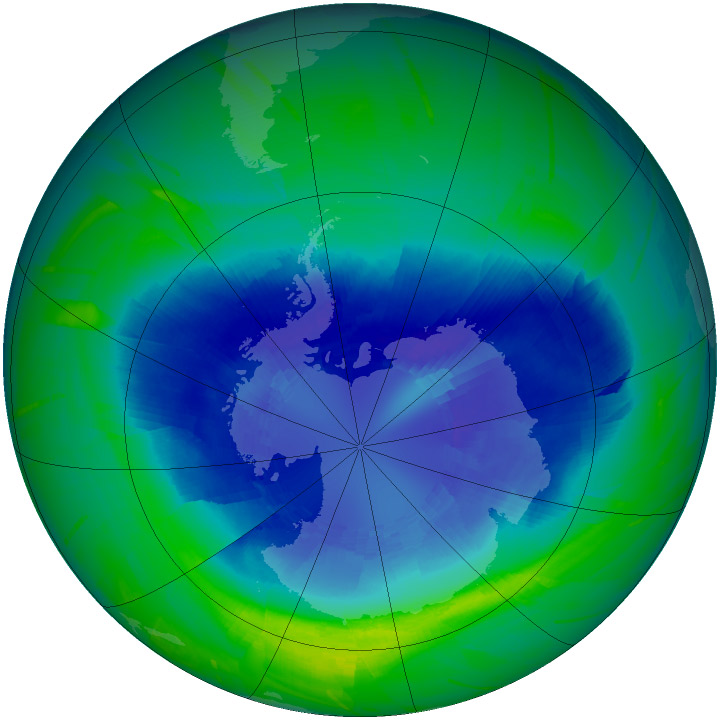

The Montreal Protocol of 1987 was signed by nearly every country in the world, pledging reductions in substances, such as chlorofluorcarbons (CFCs) that depleted the ozone layer. Since the Montreal Protocol, evidence suggests that a hole in the ozone layer, caused by decades of CFC use, had stopped expanding. Image: cc by-sa Wikimedia commons.

The Fast-Moving Science of Refrigerants

The science of refrigeration and refrigerants is complicated and fast-moving. There are thousands of different types of refrigerants, and hundreds of thousands if you include chemical blends. Every year, new refrigerants and classes of refrigerants are being introduced to the market by chemical companies like Chemours, Dupont and Honeywell. New refrigerant classes include more efficient hydrofluoro-olefins (HFOs) and HFC-HFO blends, which have lower global warming potential (GWP).

R-410A is itself a replacement of another environmentally unfriendly refrigerant. Its predecessor, R-22, was once the standard refrigerant used in HVAC systems. R-22 has been gradually phased out as part of the Montreal Protocol. In 2020, a late phaseout stage banned R-22 from production or import in the United States. (In 2030, a final phaseout stage will ban all use of R-22.) R-410A became the most common go-to refrigerant in the years since.

The widespread use of R-410A, along with a couple other broadly used HFCs, started decades ago, triggered by the initial ratification of the Montreal Protocol. The United States joined nearly every other country on earth in adopting the protocol, which, among its climate change-fighting measures, called for the elimination of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). In 1987, when the Montreal Protocol was ratified, it had become widely known that CFCs and HCFCs were highly damaging gases that were depleting the earth’s ozone layer. The ozone layer helps protect living creatures from the sun’s harmful radiation.

Around the world, HCFCs and CFCs have been in a gradual phaseout since 1987. It’s been one of the most successful global climate-related campaigns in history. Instead of the ozone-depleting HCFCs and CFCs, HFCs became the accepted norm for a time. HFCs, which contain no chlorine, have no deleterious effect on the ozone layer. As of 2000, the expanding hole in the ozone layer, measured since 1979, had evidently stabilized, an occurrence largely attributed to the phaseout of HCFCs and CFCs.

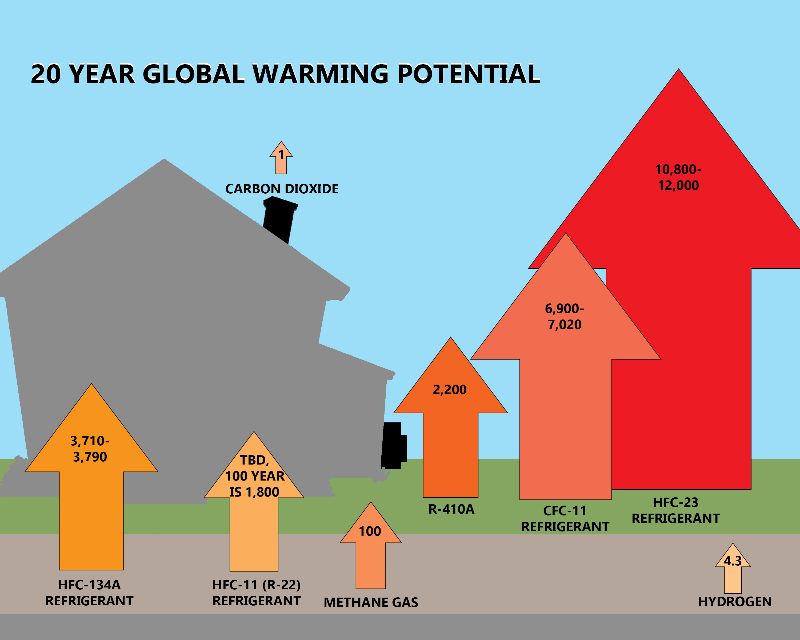

Refrigerants and other chemicals, including those that occur naturally, are assigned global warming potential (GWP) functions. GWP is a measure of a chemical’s capacity to trap heat in the earth’s atmosphere, compared with carbon dioxide, a natural chemical, which has a constant GWP function of 1. This infographic is not to scale, since the R-410A arrow is visually 26x the size of the carbon dioxide arrow. To show the difference in GWP to-scale would have required an infographic approximately 90 times larger, or else the carbon dioxide arrow would be invisible. The key difference is CO2 is emitted continuously when we burn, and refrigerants are emitted only through leakage.

The Problem with HFC Refrigerants

While HFCs have had no harmful effect on the ozone layer, they have contributed heavily to global warming. HFCs are greenhouse gases that trap heat within the earth’s atmosphere. Chemical pollutants, such as refrigerants, are assigned a global warming potential (GWP) function. GWP is a marker to determine a greenhouse gas’s capacity to trap heat in the atmosphere in comparison to carbon dioxide, a naturally occurring gas defined with a GWP of 1.

R-410A has a high GWP function of around 2,000. In 2016, as an extension of the Montreal Protocol, 155 countries including the U.S. agreed to a provision called the Kigali Amendment, to also phase down high-GWP HFCs. As part of its compliance with Kigali, the U.S. included an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulation in the AIM (American Innovation and Manufacturing) Act to phase out HFCs.

The Jan. 1, 2024, Massachusetts ban on the sale and manufacture of HFCs for commercial and industrial use precedes the federal phaseout date of Jan. 1, 2025, as decreed in the AIM Act.

R-410A Refrigerant Not Going Away Soon

The phaseout of R-410A and other high-GWP HFCs won’t be easy. We are amid an enormous global campaign to transition away from fossil fuel-burning HVAC systems toward electric systems. As a result, tens of thousands of electric heat pumps, for example, have been installed in Massachusetts homes in recent years, and millions across the U.S. Every one of those systems – in addition to window and car air conditioners, refrigerators and other cooling appliances – uses a chemical refrigerant. R-410A has been among the most common refrigerants used in residential HVAC systems in recent years, and such use is not scheduled for phaseout.

That means that the use of this and other HFCs will continue for the foreseeable future.

If these refrigerants were to be perfectly contained inside closed-loop coils within cooling and heating systems, their pollution potential would be less of a concern. But refrigerant leakage is inevitable in refrigeration systems.

Refrigerant chemicals continuously flow through pipes in order to disburse or absorb heat to and from home and business interiors. As part of their constant course, refrigerants are repeatedly pressurized and transformed from liquid to gaseous states, depending on their function of cooling or heating. Most leakage occurs during these pressurized gaseous states. Gases find their way through the tiniest holes, gaps and joints, including around poorly or unwisely installed equipment like bubble gauges, which force gas bubbles through lines to measure water levels.

Once escaped, heat-trapping gases are released into the atmosphere, a little at a time but multiplied times millions for each heat pump. Leaks can also take place during equipment repairs and fluid refills.

This 2010 NASA depiction of the ozone hole over Antarctica, shows depletion slightly reduced from measurements in 1979-2009, since the Montreal Protocol was ratified by almost every nation on earth. Our impact on the climate can be harmful and long-lasting, but it is within our power to stop things getting worse.

What About Refrigerant Safety?

Another factor that further complicates refrigerant use is the flammability of these chemicals. Most refrigerants are flammable at different levels. These chemicals are assigned one of four flammability classifications, 1, 2, 2L or 3.

Early refrigerants, like ammonia and sulfur dioxide, were highly flammable and resulted in fatal and sometimes gruesome accidents. When CFCs, with low flammability, were invented in the 1920s, the safety of refrigerant use got a boost. It wasn’t until decades later that the damage of CFCs to the ozone layer was determined. The HFC R-410A proliferated partly because of its combination of low flammability and no ozone depletion.

Now, R-410A is being phased out for some end uses in favor of low-GWP refrigerants. The EPA has imposed a target of no more than 750 GWP function for refrigerants in heat pumps, phasing in in 2025 and 2026. R-454B is becoming the new go-to.

The tradeoff is that R-454B and R-32, another broadly used chemical, both of which have low GWP, have higher flammability.

For that matter, propane also works as a refrigerant. This common gas has a negligible GWP of 0.1, though it is highly flammable. The EPA has allowed use of propane as a refrigerant in the U.S. since 2015. The European Union also allows use of propane refrigerants, as do China and India.

What Does the HFC Phaseout Mean for Mass. Consumers?

As noted above, consumers who have heat pumps and air conditioners running R-410A – and even, still, R-22 – do not have to replace or update them. The upcoming phaseout only applies to commercial and industrial end uses. However, with each new phaseout stage, high-GWP refrigerants will eventually become more limited and harder to find. Supplies of CFCs, HCFCs, and, eventually, HFCs, will dissipate. Prices will increase. In coming decades, use of such pollutants, even in residential heat pumps and air conditioners, may also be banned as part of the climate change fight.

But, while use of refrigerants like R-410A remain legal for household consumers, is it wise to continue running them and leaking them into the atmosphere?

We are in a global race to limit the effects of global warming to levels that can mitigate harmful effects on humans. If we can collectively stabilize or lower emissions of greenhouse gases worldwide, we might be able to hold the average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. While this rise is, and will continue, contributing to catastrophic weather events, like extreme heat, severe storms, droughts and wildfires, it’s much more manageable compared to a 2 degree or higher increase.

The cooperation of individual consumers in assessing and minimizing their greenhouse gas emissions from home systems and cars is essential for this campaign. Converting or swapping out HVAC systems for those running lower GWP refrigerants fits alongside measures like buying electric cars and installing solar panels.

If you’re buying new refrigeration equipment, certainly plan to purchase machines outfitted for the latest approved HFOs or low-GWP HFCs, or blends.

The Near Future of Refrigerants

It’s hard to say where refrigerant science will lead us in coming years. Newer, more efficient refrigerants are always being developed. As recently as the early 1990s, R-12 was a market standard refrigerant until R-22 replaced it. A little more than a decade later, R-22 was replaced by R-410A, still widely in use. Now R-454B, an HFO, looks to become the new standard. The concern of higher flammability has relaxed in favor of lessening global warming impact.

There’s no question that environmentally harmful chemicals need to be minimized. But our use of chemical refrigerants is not going away. As global temperatures increase, the need for cooling and refrigeration will continue to increase along with it.

Presumably, chemical scientists are at work attempting to concoct refrigerants that check all the boxes: no ozone depletion, low GWP, low flammability, reasonable price. So far, the perfect refrigerant has not emerged. How to balance our needs to be cool and keep things cool in a warming world with environmental responsibility and safety are ongoing concerns.