2017 Hurricanes Impact Rentals in Surprising Ways

| . Posted in Did you know?, News - 0 Comments

When natural disasters like Hurricane Harvey, Irma, and Maria strike, do tenants still have to pay rent? Are we safer than we used it be? Is post-storm looting the responsibility of the landlord or the tenant? Let’s look at these three questions in three US regions impacted by the 2017 hurricanes.

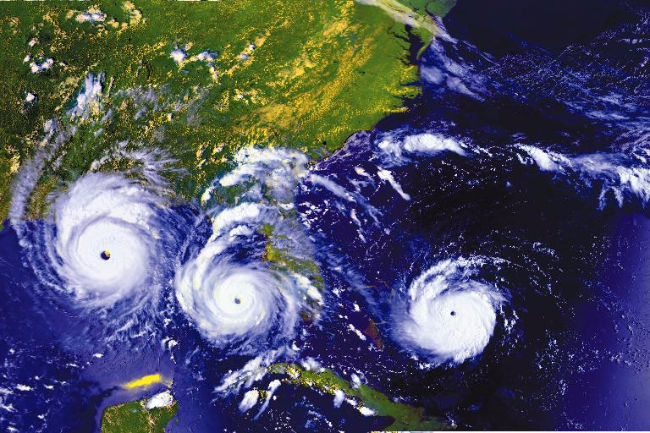

NASA time lapse collage of satellite images of hurricane Andrew, 1992. Three views of Andrew on 23, 24 and 25 August 1992 also somewhat symbolize hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria in 2017.

Texas: The “Totally Unusable” Standard

According to TexasLawHelp.org, tenants must still pay rent unless the rental property is totally unusable for residential purposes. If the property does become totally unusable, the tenant’s only unilateral option is to terminate the lease. This wording is generally favorable to landlords.

If the premises are partially unusable, for instance, if a renter can still live in the premises, the only recourse for rent reduction is to get the landlord’s agreement to reduce the rent, or to sue for a court order. In the absence of either the landlord’s agreement or a court order, full rent is owed.

This stands in contrast to Massachusetts, where a tenant can withhold rent unilaterally and defend absolutely against eviction.

Does this mean everyone in Texas has paid the rent? No. Early estimates based on FEMA pre-approvals were that up to $30 million of September rent would go unpaid. Harvey displaced 30,000 Texans. Although legally obligated to pay rent on their partially damaged apartments, likely few would have felt morally or economically able to pay for both their old premises and their replacement housing.

The Houston Housing Authority told residents they had to continue paying rent. A HUD spokesman later intervened to issue a blanket pardon.

According to data from ApartmentData.com, there were enough vacant units prior to the storm to house everyone displaced. In practice, there are three roadblocks why this hasn’t happened.

First, these vacant units were damaged along with the inhabited ones. Second, landlords must still screen their tenants, and tend not to operate like homeless shelters where almost all are welcome. Third, there has been large mismatch between the asking prices post-storm and renters’ abilities to pay, especially for tenants displaced from public housing, for which there is no market replacement.

So if you’re a Texas landlord, the rent is legally owed, but you might never see it. You should negotiate reduced rent while you wait for your insurance to complete repairs.

Florida: Stricter Building Codes Save More Property

In August 1992, Category 5 Hurricane Andrew destroyed 25,000 homes and damaged 100,000 more. In September 2017, Category 5 Irma, a bigger storm, destroyed significantly fewer, according to the Washington Post.

Florida’s population and real estate values have increased significantly since 1992, and Irma was one of the strongest storms ever recorded. Yet the economic losses reported for Andrew and Irma, after accounting for inflation, have been roughly similar. In terms of per capita losses, Irma was far less destructive.

One of the major reasons for the lower per capita cost is suspected to be the 2002 Florida Building Code, now one of the toughest in the nation. It prescribes nails for roofing (they used to allow staples), impact-resistant glass, and hurricane-force load-bearing walls, among other things. Insurers have also driven a requirement for storm shutters.

In 1992, Andrew cost between $43 to $56 billion (2017 USD). There were 13 million residents then. Per capita costs were $3,300 to $4,300.

In 2017, Irma cost between $58 and $83 billion. There are 20 million residents. Per capita losses are $2,800 to $4,000.

So if you’re a Florida landlord, the building code isn’t just the law, it’s also a good idea.

Puerto Rico: A Contract Writer’s Heaven?

In Puerto Rico, it would seem that there are few specific landlord-tenant laws. Whatever is written into the rental agreement usually prevails.

A renter offering advice to other renters makes it a point to reaffirm this in their “top thirty:”

“29. Be aware that Puerto Rico does not have tenant rights and rental laws like the US. Any litigation is part of greater civil law.”

In the Puerto Rico landlord-tenant laws, there are specific freedoms for subleasing (unless prohibited by the rental agreement) and the landlord is obligated to make repairs. But there are few other specifics.

The implications for hurricanes are interesting. If the owner or manager has not specifically offered a warranty of habitability, then a tenant whose roof blew off, who then ceased to pay rent, might still risk eviction.

It’s conceivable that the standard lease circulating among realtors and landlords in Puerto Rico will let the landlord off the hook for “acts of god” including hurricanes. It’s conceivable that the agreement will also specifically indemnify the owner for losses caused by the tenant’s negligence.

The implications for abandonment and looting are not good for tenants. Suppose the premises are rendered substantially uninhabitable, the tenant abandons the premises to seek shelter elsewhere, leaving the door unlocked because “what’s the point?”, and the premises are subsequently looted for copper pipes and working appliances. In this scenario, the average tenant might be exposed to liability claims under their rental contract.

This is purely speculative. We have heard of only one MassLandlords member’s family being in Puerto Rico, and they were able to scare off trespassers with their dogs.

In general, if you’re a Puerto Rico landlord, you have a lot of leverage. Understand your written rental agreement with your tenants, and use the leverage to help the tenants help you get the property back in order quickly.