Yim v Seattle Overturns “First in Time” Ordinance

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

In a potentially precedent-setting case, the Superior Court of Washington (State) In and For King County ruled in Yim v Seattle against the City’s “first in time” ordinance. The three major decision points concerned implicit bias, property rights, and free speech.

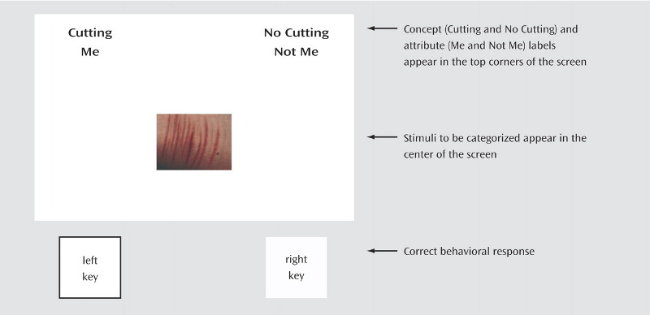

Implicit association tests to determine "implicit bias" are scientific tools with precise meaning and predictive power. This screenshot shows one test to help clinicians diagnose and treat self-harm.

Judge Suzanne Parisien granted the request of landlord Chong Yim and others for a summary judgment against the City on March 28.

What Seattle’s First in Time Ordinance Did

The “Open Housing Ordinance,” or so-called “First in Time Law,” required owners to take the first qualified applicant for an apartment. Choosing the most qualified applicant in a batch was deemed unlawful.

The ordinance spelled out the tenant screening process from advertising to selecting. Although the screening criteria were left to owner discretion, once set, owners were required to timestamp each application and take the first one that passed.

The process permitted an applicant to turn in a blank application just to hold their place in line. They could then complete their application within five days, or request a reasonable accommodation to get an arbitrarily long extension.

Tenant advocates asked for this ordinance as a way to reduce implicit bias in the tenant screening process.

Why Implicit Bias is Not What it Sounds Like

Tenant advocates and talk show hosts say that implicit bias, or unconscious discrimination, leads non-discriminatory owners to make discriminatory decisions. In fact, this is not an accurate description of the science.

So-called “implicit bias” is measured through an “Implicit Association Test” (IAT). The purpose of the IAT is to get an accurate signal about a person’s true preferences, even when they feel awkward, ashamed, or otherwise socially pressured not to speak freely. There is disagreement on whether IAT’s are more accurate than just asking someone outright.

To learn how IAT’s work, consider the following example. Some teenagers with extreme stress or anxiety resort to self-mutilation as an outlet, e.g., cutting. Clinicians used to attempt a diagnosis by asking, “Rate on a scale of 1 to 10 how likely you are to want to injure yourself without wanting to die.” Unsurprisingly, clinicians worried that not all teenagers would answer honestly.

An IAT was developed to get around this potential communication roadblock. Clinicians can now show their patient a series of pictures of cut or healthy skin. At the upper corners of the screen two of the following four phrases are shown at random: “cutting me,” “not cutting me”, “cutting not me”, and “not cutting not me.” The patient has to press a button on the left or right that corresponds to the “cutting” phrase that matches the picture in the center.

People who are thinking of cutting themselves will identify the cut skin more quickly, statistically speaking, when the phrase “cutting” appears alongside the phrase “me”. The timing differences are subtle. In this way, clinicians have learned to predict the severity of their patient’s troubles regardless of whether their patient will admit to it.

Here is the full Wikipedia list of IAT’s that have predictive power: whether a physician will recommend thrombolysis to a black patient or a white patient; whether an employer will hire a Muslim Arab man or a Swedish man; whether national attitudes toward women in STEM correlate with national achievement by women in STEM; whether someone is likely to join a pro-environmental organization; whether a pilot is likely to take unnecessary risks while flying; and whether someone is likely to develop an anxiety disorder.

To our knowledge, IAT’s have not been applied to housing. If there were a study of housing, probably IAT’s would provide no more insight than a conversation. Ask an owner, “What do you think of Section 8?” and most owners will give you an earful.

What the Judge Said about Implicit Bias

The judge made an important legal point about implicit bias:

“The principle that government can eliminate ordinary discretion because of the possibility that some people may have unconscious biases has no limiting principle – it would expand the police power beyond reasonable bounds,” Judge Parisien wrote.

This is exactly right. Judge Parisien has identified the law as defining a “thought crime,” and has nullified it.

Researchers and clinicians, of course, are free to continue to use implicit bias as they have done, as a predictive tool where honest conversation may not be possible. And the government is free to fine discriminatory landlords as they have done, on the basis of evidence of actual discrimination.

What the Judge Said about Property Rights

Judge Parisien made equally important legal commentary on property rights. She cited a case called Manufactured Housing v State, which overturned a tenant’s right of first refusal on the basis of a “fundamental attribute of property ownership,” the right to dispose of property as the owner sees fit.

She wrote that, “Choosing a tenant is a fundamental attribute of property ownership.” A lease is a disposition of an interest in the property, for a fixed duration, and therefore the owner has the right to choose the buyer of that interest. As the ordinance eliminated all choice, it eliminated ownership, and was therefore unlawful.

What the Judge Said About Speech

The ordinance regulated what owners had to disclose in their advertisement. Judge Parisien found this unlawful after subjecting it to a four-part test.

In Washington state, they can only regulate commercial speech (advertising) after considering 1.) whether it is lawful and not deceptive, 2.) whether the government interest at stake is substantial, 3.) whether the speech restriction directly and materially serves the government’s interest, and 4.) whether the restriction is no more than necessary.

The judge found the ordinance to satisfy the first two criteria. But the final two parts failed.

First, the ordinance did not directly and materially advance the City’s interest in stopping discrimination. To prove that it did would require the City use an IAT or other scientific method to identify discriminatory outcomes before and after the ordinance. The City was using the non-scientific meaning of “implicit bias,” and therefore, had no evidence.

Second, Judge Parisien found, rightly, that the “first in time policy” restricted speech more than was necessary. By barring owners from choosing the highest credit score, for instance, the ordinance was too restrictive and therefore unlawful.

Judge Parisien wrote, “A law that undertakes to abolish or limit the exercise of rights beyond what is necessary to provide for the public welfare cannot be included in the lawful police power of the government.”

King County Courthouse, where Yim v Seattle was decided.

Yim v Seattle Implications for Mass

The implications of Yim v Seattle are directly limited to Seattle and Washington state. We are in a different jurisdiction. The case does, however, provide a roadmap for finding similar case law and making similar arguments in Massachusetts or other jurisdictions.

Especially interesting is the fact that the judge identified a right of first refusal case that was struck down. This has immediate teaching power for our arguments against both Just Cause Eviction in Boston and the Tenant’s Right of First Refusal in Somerville.

Yim vs Seattle Conclusion

The broad ruling in Yim v Seattle effectively ends Seattle’s experiment with “first in time” after 15 months and 20 days.

Seattle is properly viewed as a leader in housing policy, innovating in many ways, including the Seattle Landlord Liaison Project, which MassLandlords supports. Yim v Seattle shows the importance of including landlords in crafting housing policy. What is owned cannot be taken away without permission, and owners won’t grant permission for “first in time.”

Read more on the Pacific Legal Foundation’s site.