Zoning

Zoning is the set of regulations that dictate land and building use. Massachusetts zoning policy is the primary driver of housing affordability (or lack thereof).

2019 - 2020 Session (191st)

H.3931 An Act requiring zoning for multifamily housing near transit. MassLandlords supports in principle, opposes this particular implementation on constitutional and good governance grounds.

Zoning Part One: Racist Origins, Racist Impact

By Peter Vickery, Esq., Legislative Affairs Counsel

Introduction

Members of MassLandlords know that municipalities control the distribution and scale of housing by way of zoning. This article is the first of a series that we hope will provide readers with both zoning’s historical context and an up-to-date overview of the ways it affects the rental-property business.

The cover image from the book “Sundown Towns” calls attention to a despicable early 20th century Connecticut sign. The climate in which zoning was developed was no climate for crafting housing policy.

The Green Book

In 2018 the American Film Institute recognized as one of the year’s top-10 movies The Green Book, starring Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen.

The movie’s title refers to the guide that steered African Americans away from certain establishments and neighborhoods and toward non-discriminatory ones.

The first edition of the guide came out in the era of overt segregation and “sundown towns,” which required non-whites to leave before sundown, as described in the book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism by James W. Loewen.

The last edition of the “Green Book” was published in the 1960s. But the phenomenon that made the guide necessary, i.e. race-based housing patterns, is not a thing of the past. It persists to this day. And from the early Twentieth Century onward one of the tools that municipalities have used in order to maintain racial segregation is zoning.

In the Progressive Era, several cities adopted zoning ordinances that were unabashedly segregationist. But in 1917, even with the devout segregationist Woodrow Wilson still in the White House, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down overtly racial zoning regulations in a case called Buchanan v. Warley.

Zoning itself was on uncertain constitutional ground until the Supreme Court upheld it as a valid exercise of the police power – and not a Fifth Amendment taking that required compensation – in the case of Ambler Realty Co. v. Village of Euclid, 272 U.S. 365 (1926). In Euclid, the Supreme Court made no mention of race, but lower court (which had held that the zoning ordinance was an uncompensated taking and therefore null and void) noted the commonly-offered rationale for zoning:

“The blighting of property values and the congesting of population, whenever the colored or certain foreign races invade a residential section, are so well known as to be within the judicial cognizance.” Euclid, 297 F. 307, 313 (N.D. Ohio 1924).

Often then, in northern and southern states alike, racial segregation was not a by-product of zoning but one of its key goals.

The legacy of earlier practices, and the zoning ordinances that froze the use and housing patterns that were in place at the time of adoption, ensure that racial segregation endures in schools and neighborhoods across the country, including some communities that make headlines from time to time, e.g. Flint, Michigan.

Example: Flint, Michigan

In his book Demolition Means Progress: Flint, Michigan, and the Fate of the American Metropolis Andrew R. Highsmith describes the African-American neighborhood of St. John’s Street in the North End as “virtually an island in a city.”

Highsmith points out that in Flint the 1930s when assessing mortgage applications the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) looked at its maps, which ranked neighborhoods A-D. African-American areas were graded D and shaded red. HOLC routinely denied applications in red-lined areas and gave preference to properties in neighborhoods where deed and zoning restrictions excluded “low grade populations and different racial groups.” Similarly the Federal Housing Administration tended to deny mortgage insurance in C and D areas, i.e. African-American and racially mixed neighborhoods.

Racially-restrictive covenants remained lawful until 1948 when the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional in the case of Shelley v. Kraemer. That ruling did not render them suddenly ineffective, however. During the decades when they were constitutional, restrictive covenants had a role in shaping housing patterns, which other tools helped reinforce. Highsmith calls these tools, such as gerrymandered school-attendance districts, “administrative Jim Crow.”

These practices were not confined to Flint, of course, and they have adapted over time.

Exclusionary Zoning

The term “exclusionary zoning” refers to restrictions such as lot sizes, square-footage, and density requirements that are neutral on their face but have the effect of limiting the number of low-income and racial-minority people who can live in particular neighborhoods. It is a way of preserving “enclaves of affluence and social homogeneity,” as one judge put it.

Readers interested in learning more about the history and effects of exclusionary zoning may want to read “Neighborhood Upzoning and Racial Displacement: A Potential Target for Disparate Impact Litigation,” by Bradley Pough, who currently clerks for Judge David Barron of the First Circuit Court of Appeals.

In addition to racial segregation, exclusionary zoning perpetuates wealth disparities. And, as Richard V. Reeves of the Brookings Institution points out, the most restrictive regulations are in the more liberal communities in liberal states, such as California, New York, and Connecticut.

Some may find this ironic. But given zoning’s roots in the so-called reform of the so-called Progressive Era, it should not come as any surprise that individual civil liberty suffered worst where the state was strongest. When we look to Massachusetts, a supposed bastion of liberalism, freedom, and progress, we must look very skeptically at the state indeed. The zoning enacted a century ago continues to fulfill its invidious purpose of restricting who is free to live where.

Zoning Part 2: Home, the Forbidden Zone; Our Zoning Regulatory Framework

By Peter Vickery, Esq. Legislative Affairs Counsel

Zoning in Massachusetts is regulated by cities and towns via the authority granted to them in M.G.L c. 40A, 40B, and 41. It’s important to consider what people used to expect from their communities prior to the passage of these laws, and how these laws constrain us today.

This colonial house in Old Sturbridge Village lacks the required parking to be permitted today. Nevermind there are no cars intended to travel on this street, the building and the neighborhood could not be built anywhere in Massachusetts today. CC-BY-ND Massachusetts Office of Tourism.

Living the Dream

Place matters. Where we are — our physical setting — affects how we feel about ourselves and the people around us, even when we are oblivious to what it is, exactly, that is producing these feelings. Some places put us on edge. Others (usually quiet places without cars, neon, and LED) have a very different effect, tending to make us feel comfortable and at home whether we have been there before or not. They induce a feeling of poignancy, something akin to nostalgia, a sense of belonging and wanting to stay.

If you have ever visited Old Sturbridge Village in Worcester County, Massachusetts, or Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, you may have experienced this sensation, knowing that you are in a place of metes and bounds, rods and furlongs, woodsmoke and livestock, of things carved, stitched, or wrought by hand and paid for with heavy coins. The buildings and the spaces between them feel right. Pretty much wherever you go you can see the few landmarks (bridges, barns, and steeples) so you know that it would be hard to get lost. There is joy deep inside as you soak in the beauty of a place where the houses look like homes; where people work and dwell in the same space; where trees grow along the sidewalks; and where the plots, gardens, and fields are marked off from one another by wooden fences, stone walls, and hedgerows. You sense harmony and deep roots, and feel a profound conviction that this is how a town—a hometown—should be.

For the good of your heart and soul, you should think about that place. Just don’t try building it. The planning board won’t let you.

Somewhere or Anywhere, but Nowhere

That jarring realization of zoning’s stifling effect will come to any reader of James Howard Kunstler. Given to presenting his opinions in a manner that one could most generously describe as forceful, Kunstler is the author of several books on the subject of the built environment and zoning, including The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape; The City in Mind: Notes on the Human Condition; and Home from Nowhere: Remaking Our Everyday World for the 21st Century.

Kunstler has long pondered the reasons why so many places look the same (drive across the country, look out the car window, and much of the time you could be anywhere). Such sameness instills ennui in the individual and anomie in society as a whole. He has concluded that one of the biggest culprits is zoning.

In an episode of his podcast, KunstlerCast, he discusses the evolution of zoning from its origin as a response to the health effects of heavy industry to its current manifestation that segregates residences from retail stores (effectively classifying shopping as “an obnoxious industrial activity that nobody should be allowed to live anywhere near”) thereby encouraging strip malls, gutting the traditional downtown Main Street, and requiring people to drive everywhere. Sprawl, smog, suburban seclusion: name the blight, zoning made it (or made it worse) says Kunstler.

For a taste of Kunstler’s writing, try his article from the September 1996 issue of the Atlantic magazine, in which he makes a memorable proposal for dealing with zoning bylaws:

“Don’t revise them — get rid of them. Set them on fire if possible and make a public ceremony of it.”

Certainly, Kunstler exaggerates for effect. But is zoning really so bad that we should put a metaphorical match to it? After all, the modern purpose of zoning (putting to one side its partly racist origins) is ostensibly to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the public as a whole. It can help preserve green space, historic buildings, and cultural features. And rules differ from community to community thereby creating choices: If you don’t like the way they do things in Town A, move across the line to Town B where they do things differently. But if state law limits the zoning differences, it also limits people’s choices.

Before deciding whether to follow Kunstler’s advice and build a bonfire of the bylaws, let’s learn a little more about the basics of zoning in Massachusetts.

"Don't talk about public transportation. We just want to know what's going on here." Christine Araujo, Chair of the Boston Zoning Board of Appeals, shutting down an applicant for a variance who lacked the required parking but who was within walking distance of MBTA stops. April 27, 2021

The Dillon Rule and Home Rule

In 1868 John F. Dillon, a justice of Iowa’s highest court, stated that municipalities derive their power from the legislative bodies of the State. The Supreme Court of the United States endorsed that view in 1907.

Under the Dillon Rule, Massachusetts towns have only as much power as the State Constitution and the Legislature grant them. In 1966 the voters ratified article of amendment 89 to the State Constitution (titled the Home Rule Amendment). Section 6 provides that any city or town may “exercise any power or function which the general court has power to confer upon it, which is not inconsistent with the constitution or laws enacted by the general court in conformity with powers reserved to the general court by section eight, and which is not denied, either expressly or by clear implication, to the city or town by its charter.” The main power reserved to the Legislature by section eight is the power to enact laws that apply to all towns and cities of the Commonwealth equally (such as the power to levy taxes and borrow money) unless a particular community asks the Legislature for a special law that will apply to it alone.

What does this mean in the context of zoning? Municipalities are allowed to enact their own rules (called ordinances in cities and bylaws in towns) but only within the parameters set by the Legislature in the Zoning Act, M.G.L. c. 40A, the most revised version of which took effect in 1976. This statute establishes the zoning framework for all Massachusetts communities except Boston, which has its own law called the Boston Enabling Act.

Chapters 40A and 41

Zoning bylaws and ordinances differ from community to community, but what most of them have in common is complexity. Each municipality’s zoning consists of maps of the various zoning districts (e.g. residential, commercial, industrial), a chart of uses, and a chart of dimensional requirements. There may also be overlay districts, superimposed on the underlying districts. Together, these components are supposed to promote a variety of concerns, such as fire safety, water supply, aesthetics, and conservation. They may also contain additions designed to promote mixed use (such as a mixture of multi-family housing together with retail, restaurants, and offices) and to encourage affordable housing, e.g. “inclusionary zoning” provisions.

The Zoning Act prescribes the way a municipality can adopt and amend its zoning rules, grant variances and special permits, and handle appeals.

Some uses are allowed “by right” or “as of right” and do not require discretionary review by the local permit-granting body. Even if a particular project is not allowed by right, the owner of a piece of property (or someone who is about to buy it) can apply for a special permit.

For example, an owner may want to build housing that would be denser than allowed in the particular zoning district. They will need to apply for a special permit under section 9 of the Zoning Act. Section 10 governs variances, i.e. deviations from a particular requirement of the bylaw/ordinance, and sets a high bar for applicants. A “person aggrieved” by a decision about a special permit or variance has 20 days to appeal, starting from the day the decision is filed with the town/city clerk. For a detailed description of special permits and variances, check out Attorney Richard Vetstein’s Mass Real Estate Law Blog posts on the subject.

Section 32 of the Zoning Act provides that before a new zoning bylaw/ordinance can take effect the municipality has to obtain approval from the Attorney General. Section 3, known as the Dover Amendment, contains a special rule for religious organizations and nonprofit educational institutions, and says that zoning ordinances and bylaws are not allowed to:

“prohibit, regulate or restrict the use of land or structures for religious purposes or for educational purposes on land owned or leased by the commonwealth or any of its agencies, subdivisions or bodies politic or by a religious sect or denomination, or by a nonprofit educational corporation; provided, however, that such land or structures may be subject to reasonable regulations concerning the bulk and height of structures and determining yard sizes, lot area, setbacks, open space, parking and building coverage requirements.”

A separate statute, the Subdivision Control Act (M.G.L. c. 41) regulates the way property owners go about subdividing of parcels of land into building lots.

Together, the Zoning Act and the Subdivision Control Act provide ways for local governments to control the pace of development, population density, and the intensity of uses. For example, communities can encourage pricier housing so as to preserve property values (and simultaneously deter affordable housing) by way of zoning rules that make it more expensive to build houses, e.g. minimum lot sizes, minimum frontage, and set-back requirements.

Chapter 40B

Because of the way zoning can keep housing prices high, the Legislature enacted a third statute, the Comprehensive Permit Act, known as Chapter 40B. This law enables affordable-housing developers to avoid a community’s density strictures if the current level of affordable housing is less than 10% of its total housing stock.

Sustainability, Smart Growth, and Patchwork Reform

In addition to thwarting the production of affordable housing and degrading the traditional Main Street, zoning as it has evolved since the 1940s has often encouraged dependence on motor-vehicles and discouraged walkable neighborhoods. In an attempt to tackle these problems, policymakers in Massachusetts have come up with several approaches, such as Open Space Residential Design, Form Based Codes, and Traditional Neighborhood Development.

Suffice it to say, without either these reforms or a zoning code bonfire, you are not free to build your dream abode in the place or manner of your choosing.

Future editions of the newsletter will describe the role of various zoning reform proposals in the ongoing conversation about zoning, and whether they offer a more pragmatic alternative to the Kunstler bonfire proposal. In the meantime, readers can find out more about these and other ideas from the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (for instance, the OSD/NRPZ Tool).

Zoning: Part 3: The Housing Choice Bill, and a Counterproposal

By Peter Vickery, Esq., Legislative Affairs Counsel

This third installment of the series on zoning takes a look at Governor Charlie Baker’s proposal to remove the two-thirds supermajority requirement for zoning changes, and at one counterproposal from some of the bill’s opponents. Let’s begin by considering why some changes are in order.

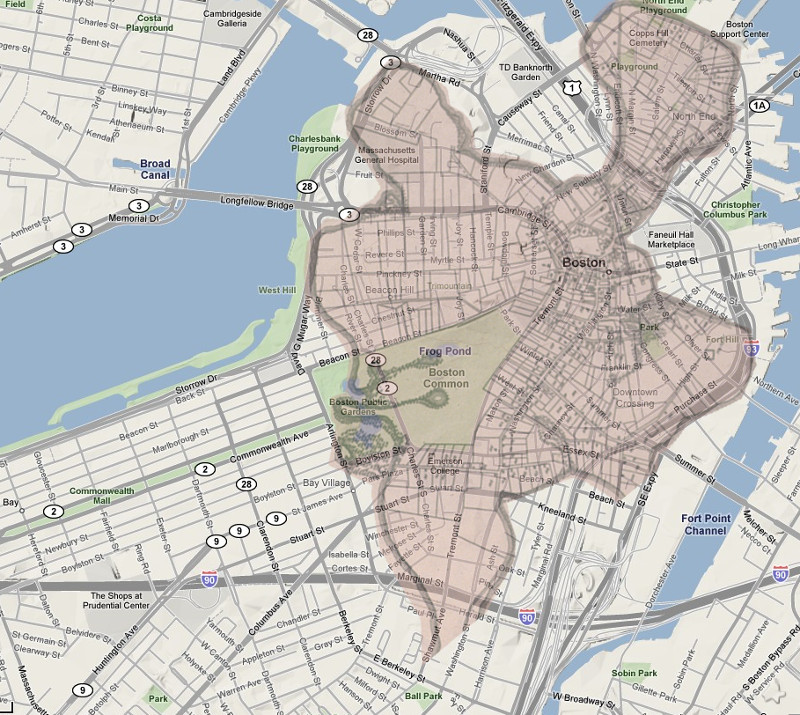

Map showing original extent of Boston, and land added by fill and annexation. BostonGeology.com: http://bostongeology.com/boston/casestudies/fillingbackbay/fillingbackbay.htm

Zoning: For When We Aren’t Making More Land

Massachusetts needs more houses, approximately 17,000 per year in and around Greater Boston alone, according to the Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Despite the widespread agreement about the need for new homes, developers are struggling to find space to build them.

Once upon a time when Boston ran out of land, it just made more, like the Dutch with their polders.

In the 1800s, Bostonians dug away at a number of hills (including Beacon Hill, which used to be 60 feet higher than it is today) and poured the resulting fill into bodies of water, e.g. Back Bay. Yes, back in the day Back Bay was a bay.

The results were dramatic, as you can see from National Geographic’s online map that shows how Boston grew from a mere 800 acres on the Shawmut Peninsula to its current size of closer to 57,000 acres.

Fortunately, flattening hills and dumping them into to the sea has fallen out of favor among Bay State policymakers. In fact, the Attorney General takes a dim view of such activities, as C&G Land Reclamation and Renewable Energy Solutions, LLC, learned after they chose the wetlands area across the street from an elementary school in Salisbury as the site for depositing concrete rubble and other assorted items of solid waste.

Land reclamation is off the table for all but those with the time, money, and other resources to obtain the necessary wetland permits from the Department of Environmental Protection (applicants should not hold their breath). The more practical and environmentally sustainable approach is to make better use of the buildable land already available. But in order to change the way we use land, we need to change our zoning laws.

In February 2019 Governor Charlie Baker re-filed his bill titled an Act to Promote Housing Choices (191-H.3507-HD.4036), which would amend the Zoning Act (chapter 40A) by abolishing the two-thirds supermajority requirement for certain zoning changes for communities other than Boston. Readers of previous articles in this series will recall that Boston has its own zoning statute, 1956 Mass. Acts, chapter 655. Re-filing was necessary because in the previous session the bill’s precursor expired in committee.

Zoning Sticks and Carrots

Zoning, by its very nature, restricts housing choices. It allows housing in certain areas but prohibits it in others. Each of the 351 municipalities in the Commonwealth has its own zoning bylaw or ordinance with little in the way of mandatory regional planning, the most well-known exception being the Cape Cod Commission.

There are some express limits on what municipalities can use their zoning to achieve. For example, Section 3 of Chapter 40A lists the uses that a municipality may not prohibit or regulate unreasonably (e.g. solar energy systems and group-homes for people with disabilities). The officer of government responsible for policing this aspect of the Zoning Act is the Attorney General, to whose Municipal Law Unit towns and cities have to submit zoning amendments, including changes to their zoning maps.

In addition to the clear prohibitions, in communities where less than 10% of the housing stock meets the statutory definition of “affordable” Chapter 40B allows developers of affordable housing to proceed despite local opposition. That said, there are certain safe-harbor provisions that allow communities to deny permits even if they are below the 10% level.

While Chapter 40A contains some simple thou-shalt-nots, and Chapter 40B amounts to a more nuanced thou-shalt-if, other statutes try to nudge municipalities in the direction that the Legislature has deemed to be right. For example, Chapter 40R (titled Smart Growth Zoning and Housing Production) provides financial incentives for mixed use and affordable housing. Similarly, Chapter 40T lets the Department of Housing and Community Development step in to help a community preserve its publicly-assisted affordable housing by giving the Department the right of first refusal to purchase properties when the owners want to sell.

Even with this combination of laws, local control over zoning still impedes the scale of house-building that Beacon Hill sees as essential for the Commonwealth to meet anticipated housing needs. Encouraging communities to change their zoning so as to accommodate statewide priorities has proved so hard that some politicians think the situation calls for more drastic measures: less honey, more vinegar.

Multifamily Housing Near Transit

Among those opposing the Governor’s legislation is Representative Mike Connolly of Cambridge (a member of the Joint Committee on Housing). Representative Connolly wrote that the Legislature should wait on Baker’s bill until it becomes part of a bigger package that includes “smart, regional production strategies, stronger tenant protections and anti-displacement measures, and additional tools for raising revenue to support affordability and end homelessness.”

Newsletter readers will be familiar with the meaning of the terms “stronger tenant protections,” “anti-displacement measures,” and “additional tools for raising revenue.” These proposals lack landlord input or agreement.

Representative Connolly filed a bill titled “an Act requiring zoning for multifamily housing near transit” (191-H.3931-HD.1118). It takes aim at cities and towns with buildable land situated within one mile of “a commuter rail station, subway station, ferry terminal or bus station” that fail to “provide for multi-family residential development.”

If enacted, the bill would require the Governor to “withhold from such city or town public funds from any state agency” and require the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) to punish the community with a surcharge. Representative Connolly and the bill’s co-sponsors (there are more than a dozen of them) want communities to adapt their zoning codes to encourage housing within walking distance of public transportation. Those that fail to comply will receive no state aid of any kind, apparently, until they are embargoed, sanctioned, and stigmatized into submission. The policy rationale seems simple enough: What works against Syria and North Korea should work equally well against Scituate and North Andover.

On the question of the Governor’s legal duty to turn off the financial faucet, the language is contradictory. Subsection (a) gives the Governor an unambiguous mandate (“the governor shall withhold” funds) whereas subsection (b) grants him discretion (“in considering whether to withhold funds”). Then there is the matter of separation of powers. Questions come before the courts from time to time about if and when a governor may impound monies already appropriated by the Legislature, and the extent to which the Legislature may compel the Governor to spend. It is a gray area. Beyond dispute, however, is the draconian nature of 191-H.3931-HD.1118 in completely cutting off funds to communities for their inadequate zoning. (Such a harsh measure did not even befall Nantucket when it unilaterally surrendered to the British— effectively seceding from the Commonwealth and Union—during the War of 1812.)

Current law would not impose this level of punishment on a city that first dedicated half its school budget to sending the mayor, council, and their friends and relations on a Caribbean cruise, and second blew the other half at Foxwoods. The proponents of 191-H.3931-HD.1118 must really want multi-family housing near public transit.

Even putting to one side the inartful drafting, dubious constitutionality, and sledgehammer/nut issues, we are still left with a question of enforcement. What would happen if the Governor declined to lay financial siege to a recalcitrant community? Who would have standing to rush to court for an injunction prohibiting him from signing the checks? The bill does not say.

Nor does it seem to account for the existence of Central and Western Massachusetts. For example, if the bus company in Hinsdale, Berkshire County, moves its bus station slightly to the east, closer neighboring Peru (population 847), will Peru then suffer a surcharge at the hands of the MBTA? If so, how exactly will the MBTA, whose service area goes no further west than Concord (some miles short of Berkshire County) levy the fine? These are important questions that, in all likelihood, no one will ever have to answer. The bill is unlikely to pass in any form.

A more realistic bill would be a welcome addition to the repertoire of responses to the Bay State’s pressing need for more housing, both market-rate and affordable. Siting multi-family homes close to public transit in walkable neighborhoods makes sense, and zoning rules should not stand in the way.

Act to Promote Housing Choices

What, then, of Governor Baker’s re-filed proposal to change the way communities amend their zoning codes?

One Blue Mass Group (clearly not a fan) described it as “a pure supply-side scam, designed to line the pockets of land speculators, property developers, and realtors, which will primarily result in more luxury condos for the super-rich to invest in.”

The bill does indeed, as Representative Connolly points out in his blog, rely on the “single strategy” of replacing the requirement for a two-thirds supermajority with a simple majority. Rather than an advantage, the bill’s simplicity strikes its progressive opponents as problematic. Judging by their comments, the game-plan seems to be to block Baker’s efforts unless and until they are combined with the above-mentioned “stronger tenant protections,” “anti-displacement measures,” and “additional tools for raising revenue” or, in plain English, taxpayer-funded lawyers for tenants, an end to no-cause-stated eviction, and higher taxes.

As the current session ends without the Legislature voting on the Housing Choices proposal, MassLandlords members need to keep a weather eye on Beacon Hill. With no wind in the sails of his bill, Baker may be tempted to tack left to get out of the doldrums. Housing partisanship leaves little chance of bridging the gap toward true consensus. And landfill -- easy though it may have been in a less regulated, less climate-vulnerable world -- is a solution best left in the past.

Further Reading

- Related Article: The ‘Affordable Housing’ Fraud

- Related Article: Affordability Crisis? Try Zoning, Not Rent Control

- Related Article: What is to be done about “flipping” & displacement? (October 2016)

External Links

- National Zoning Atlas, Cornell University

- Resort Was an Oasis for Blacks Until Racism [, Land Use] Drove Them Out", Los Angeles Times, July 21, 2002

- The Racist History of Single-Family Home Zoning KQED, October 5, 2020

- Board rejects apartment building near Ashmont T station for lackof parking, being too big for its lot, too tall for the neighborhood, Universal Hub, Adamg. Mentions Christine Araujo and Councilor Brian Worrell.

Want to do something quietly on your own land but can't?