Local Control of Housing Policy: A Bad Idea. An Open Letter to the Joint Committee on Housing

The Joint Committee on Housing will report a slew of bills on rent control (H.1378, H.1440, H.3721, H.4229, S.886, S.889) and right of first refusal (S.890, H.1426, H.4208) between March 1 and May 9. These bills would ask the legislature for local or “home rule” permission to amend state law within city limits to enact rent control and right of first refusal policies. These bills represent a crisis in policy education. This is not a letter opposed to rent control or right of first refusal (although we do oppose both policies). This is a letter opposed to local control of housing policy.

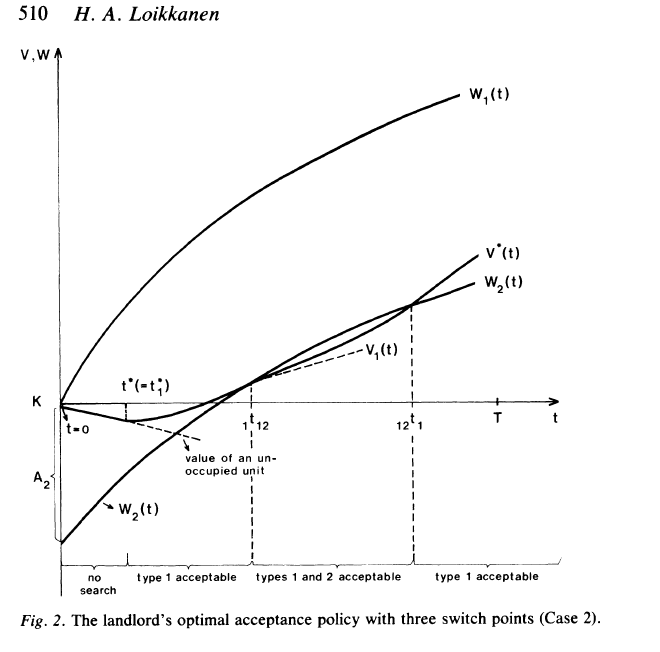

You don't need to understand this graph to know that we're serious about opposing rent control. Loikkannen (1985, Academy of Finland) proves why rent control created disparate impact.

Three Problems with Local Rent Control

During a Jan. 12, 2022, interview on Boston Public Radio between Jim Braude and Rep. Mike Connolly (Middlesex), Jim asked, speaking to a hypothetical legislator outside of Boston, "Why do you care and what is it your business what Michelle Wu does to provide affordable housing in Boston?"

1.) As we hope you will recall, rent control was repealed in 1994 by statewide ballot initiative. The issue then was the perception that rent control in Cambridge, Brookline and Boston artificially suppressed real estate prices, assessments, and local tax revenue there. This resulted in increased state aid to these communities relative to communities that had not adopted rent control. An opponent of rent control would have described it as akin to allowing Cambridge to shoot itself in the foot while other towns paid for the ambulance.

2.) What we also knew at the time, but which was less pressing then than now, is that rent control decreases housing supply. Tenants stay longer in rent-controlled units. These controlled units are then effectively off the market. The numbers vary by study. A 2009 study by the American Institute for Economic Research showed the end of rent control was “associated with a 6% point increase in the probability of a unit being a rental.” One study, extrapolated to today’s demographics, shows that applying rent control would be equivalent to a 16,000-unit reduction in Boston alone, and would result in spiking rental prices in surrounding towns.

3.) The final point is something we have learned since rent control was repealed in 1994. David Sims (2007, Brigham Young University) found a disparate impact effect predicted two decades earlier by Heikki Loikkanen (1985, Academy of Finland): Rent control had unintendedly exacerbated systemic racism, even in the presence of strong protections in the commonwealth against personal racism. Landlords under rent control, who could only charge so much for rent, held their units vacant longer, to wait for a tenant with better credit, higher income, less criminal history and fewer evictions. As you know, there is an unfair black-white gap in all four of these metrics:

The Economic Policy Institute shows that 2018 median household income nationally was $41,692 for black households[1] and $70,642 for white households. ApartmentList shows black households are more than twice as likely to be evicted[2] as white households. The Urban Institute shows 21 percent of black households have a FICO credit score above 700[3], whereas 50 percent of white households do. And a report from the Sentencing Project shows African Americans constitute 53 percent of drug convictions[4], despite representing 14 percent of drug users.

During rent control in Massachusetts, people of color occupied 12% of controlled units, despite representing 24% of the community. When rent control was repealed, this disparity disappeared.

Local control is not the answer to housing policy. We can agree that no town should be able to enact Jim Crow or segregation laws. That's explicitly racist. Well, no town should be allowed to enact rent control either, absent a complete redress for systemic racism on rental applications. That's a real hard problem that is not close to being solved by any of the rent control bills, or any other bill, before the legislature.

And we'll add: single-family zoning is the root cause of the problem and the epitome of local control. That, too, should be viewed critically.

Single-Family Zoning Must Be Reformed

Property owners who choose to should be allowed to construct multi-families or accessory dwelling units (ADUs) on their property as long as their plans comply with building code. Homeowners who choose to have a single-family house on a lot with several acres should be free to, of course. But those who choose to benefit by offering housing options on their lots should have that option too.

Single-family zoning laws disallow such options. By design, these laws were put in place to prevent black and brown people from living in good neighborhoods. And for a century, single-family zoning has deterred growth in affordable housing that could have been substantial. Our housing crisis has worsened each year since, and has landed disproportionately on Bay Staters of color.

There is no shortage of examples of other states and communities across the United States taking steps to undo the racist past and reform single-family zoning. California and Oregon lead the way among states creating laws intended to expand housing through zoning reform.

California has passed[5] a slew of recent bills, packaged as Building Opportunities for All[6], that allow property owners to subdivide parcels in two in order to build extra dwellings, such as duplexes and ADUs. Another bill gives municipalities the option to rezone neighborhoods in transit-rich and/or urban/infill areas to allow increased gentle density of up to 10 homes per parcel. Other new laws in California allow residential housing to be built on commercially and retail-zoned properties, enable gentle density and provide support for affordable housing projects, among other measures.

Oregon passed a law in 2019 disallowing cities with populations of more than 10,000 people from preventing duplex and townhouse construction on single-family zoned land.

In 2020, Minneapolis, Minn., became the first major U.S. city to ban single-family zoning in every neighborhood as part of its Minneapolis 2040[7] comprehensive plan. The policy bans the prohibition of building duplexes and triplexes on single-family zoned land citywide. Washington, D.C., has taken recent steps to allow the construction of ADUs in most residential zones.

In Massachusetts, the Housing Choice Law[8], passed in 2020, was a start.

Now in Massachusetts, many (especially those who advocate for rent control) are uncomfortable with how markets work. To reform single-family zoning is not to say that the market should be entirely deregulated or that housing should be a free for all. On the contrary, markets can fail in ways with clear externalities (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions) and must be regulated.

We urge our legislators to seek zoning reform similar to that in other states and that extends Housing Choice Law provisions.

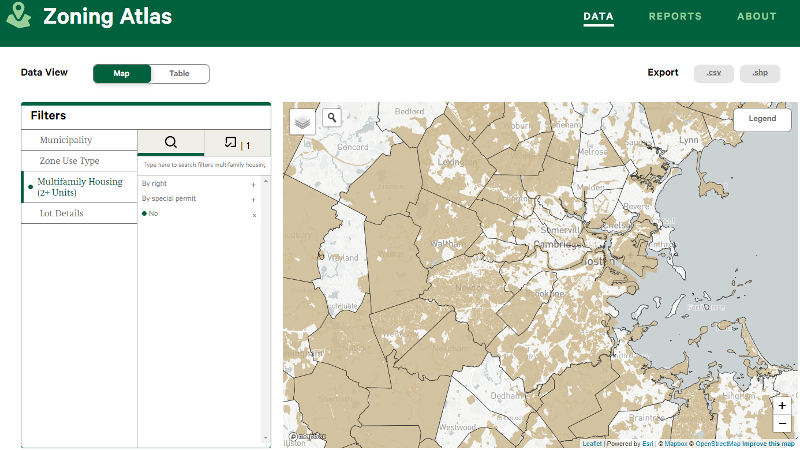

The MAPC Zoning Atlas shows that huge swaths of areas perceived as dense no longer allow creation or restoration of 2+ units on a single lot (brown), even with special permission. More than half of Boston is now effectively single family.

If the Legislature Won’t Further Reform Zoning, Prevent Rent Control, Courts Will Decide

With the data available publicly, any rent control system would be immediately challengeable under Title VIII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1968 (the Fair Housing Act). It doesn’t matter which buildings are exempt or not, or whether the allowable rent increase is above or below CPI. These refinements are the proverbial rearranged deck chairs on the Titanic. Rent control is not a solution on any scale.

Depending on how MassLandlords brings any case, the impact could be far broader than just overturning rent control. Based on the history and data available to us today, an argument could be brought to invalidate rent control and single-family zoning in a single action. That’s how bad local control of these exclusionary policies has proved to be.

Local control must never exclude: Local control has been used to reduce supply, drive people out of town and make housing more expensive everywhere else. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote from jail, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” We must work diligently to eliminate systemic racism in Massachusetts and to correct the housing market by statewide – not local – action.

For further investigation of zoning and the hidden way it makes even dense-looking neighborhoods effectively single family (in the event of a fire, the multifamily cannot be rebuilt), we refer you to the MAPC zoning atlas[9]. This master database of Greater Boston zoning lays bare the problem for all to see.

We would be happy to discuss these issues with you any time, either one-on-one or among you and your colleagues.

Sincerely,

Eric Weld

Journalist, Writer, and Editor

Douglas Quattrochi

Executive Director

MassLandlords, Inc.