Housing Surety Bond Spreadsheet Models Costs Now, Savings Later

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

Massachusetts has an opportunity now — starting with a $13 million investment that retroactively covers April — to guarantee that renters across the state can remain in their homes with the backing of a state-issued surety bond. Unlike the eviction moratorium recently signed by Governor Charlie Baker, which will end and which leaves landlords with no ability to cover housing costs for the period of the moratorium, the surety bond would achieve greater public health benefit with less economic damage. Our spreadsheet model explains how it works.

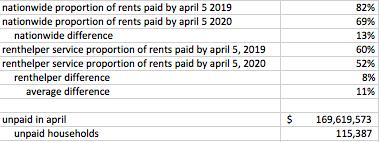

This model estimates 11 percent of rental households unable to pay bills, based on an average of reported unpaid rents taken between April 5, 2019, and April 5, 2020 (image: CC BY-SA MassLandlords).

A surety bond is a guarantee of a rental contract. Surety bonds outlast all other pandemic responses. Landlords will have peace of mind that they will eventually be reimbursed for providing housing. Renters will have peace of mind that they will not lose their homes even in the aftermath of the pandemic as they work to recover financially.

Investing in a state-issued surety bond now will save potential billions of dollars later by making the curve flatter faster. The longer such a solution is delayed, the more expensive COVID-19 will eventually become for Massachusetts.

How Much Does it Cost?

Using statistics from the U.S. Census, state government and other reporting, MassLandlords compiled a spreadsheet model that details estimated costs of a housing surety bond. In short, the cost of the bond is the total of all rents unable to be paid minus the total of all federal and state safety net payments, including unemployment.

This proposal calls for a surety bond that includes a retroactive guarantee for April. Many rents went unpaid in April as millions of renters lost jobs, and as the state eviction moratorium went into effect. We calculate a cost of $13 million to guarantee all April rents.

To arrive at this figure, we subtracted the amount of scheduled relief payments —including a one-time direct payment of $1200 to each taxpayer as part of the CARES Act, plus federal and state unemployment support — for the month (totaling $494.7 million) from the estimated amount of unpaid bills among Massachusetts renters, including rent, due to coronavirus response ($537.1 million); then factored 30 percent of that amount, an estimation of the rent portion of total household bills. The April dollar amount represents approximately .02 percent of the state government’s $57 billion fiscal year 2020 budget.

We use the data that 11 percent (more than 115,000) of the state’s 1.1 million rental households have been unable to meet their April rental expenses for coronavirus-related reasons. Eleven percent is an average taken between reporting agencies comparing rents paid nationally by April 5, 2019 (71 percent) to those paid by April 5, 2020 (60 percent).

We assume an average rent statewide of $1,470 per month (taken from U.S. Census, 2014-2018, median gross rent nationally, of $1,225, per month and adding a 20 percent estimate for increase and other market pressures). Eleven percent of this market equals $169.1 million.

We subtract 5 percent of renters who are not paying for reasons other than coronavirus (e.g. “rent strike” participants or others who are employed but decide not to pay rent). This leaves us with $161.1 million in unpaid rent related to coronavirus inability to pay, among 109,618 households.

It is known that rent is 30 percent of total household monthly expenditures. This means that an additional 70 percent of bills are potentially going unpaid, bringing the total in unpaid household obligations to $537.1 million. By subtracting total expected relief payments of $494.7 million, we arrive at a shortfall of $42.4 million in unpaid household bills for the month of April. Thirty percent of that amount (representing the rent portion of household bills) equals nearly $13 million.

Importantly, these estimates account for undocumented individuals, an estimated 3 percent of the state’s population (215,121 individuals, or about 90,363 households). For this population, a surety bond is essential because they are not eligible for CARES Act payments or state or federal unemployment relief. This means undocumented workers are more likely to venture outside their homes seeking employment, taking public transportation, and potentially spreading the virus.

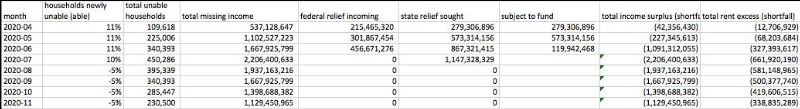

Monthly costs for a housing surety bond would increase through July before receding in subsequent months. (image: CC BY-SA MassLandlords)

More Expensive by the Month

If we cannot substantially eliminate the spread of COVID-19, our economy will remain shuttered for months. Each month the number of renter households unable to pay will increase.

In May, short of further stimulus from the federal government, the price tag for a surety bond guaranteeing housing climbs substantially, to $68 million. This is due in part to the absence of a CARES Act stimulus payment to taxpayers. But the increased May total also projects a continued increase in unemployment among renters as more businesses falter, lay off employees and close.

Another 11 percent of rental households unable to pay bills brings the May total to 225,000, with unpaid expenditures equaling $1.1 billion. Subtracting expected federal unemployment relief of $301.8 million, which continues into May, and state unemployment payments of $573.3 million ($875.1 million total), the result is a May shortfall of $227.3 million. Again, taking 30 percent of that total, we have $68 million.

The June cost for a surety bond continues this exponential increase, to more than $327 million. Again, this figure assumes an additional 11 percent of households unable to pay bills as the statewide lockdown stretches into its third month. However, in June, the state’s unemployment reserve, currently at $1.63 billion, would be exhausted and able to cover less than 14 percent of unemployment claims, adding to the surety bond cost.

In July, the fourth month of stay-at-home orders, the surety bond cost doubles, to $662 million, as federal relief runs out (state relief was exhausted in June).

Not until the fifth month, in August, would we hopefully see a return to economic activity and our first decrease in cost of a surety bond, receding to $581 million. This presumes a slight uptick in employment as coronavirus cases decline and the percentage of households unable to pay their bills decreases by 5 percent, a trend that continues for subsequent months in this model.

A surety bond can be inexpensive if issued with a sharp curtailment in what constitutes “essential” activity and extensive contact tracing, so that spread can be stopped entirely and not dragged out for months.

Action Needed Now to Reduce Future Costs

It’s important to note: with early action on a surety bond, people in rental housing will be more likely to obey stay-at-home orders with the knowledge that they will not be evicted for nonpayment due to coronavirus. Without such a guarantee, many renters continue to leave home each day seeking employment and income in order to pay their rent, fearful of losing their homes after the moratorium. As they do, a percentage of them may be spreading coronavirus without knowing it, prolonging the state’s effort to reduce the number of cases, and delaying the time at which we can begin reviving the economy.

It is possible that action taken by the state government now to guarantee housing may alleviate the need for future intervention by positively influencing the coronavirus recovery. The projections in this spreadsheet model necessarily rely on current trends, and on federal and state relief based on today’s numbers: CARES Act direct payments; federal unemployment, scheduled at $2,580 per month; and state unemployment of $4,900 per month (this is based on an application estimate of 52 percent among eligible unemployed, twice the normal average) while funds last.

Further stimulus for taxpayers, and to federal and state unemployment, may help offset these projections, and may help dampen projected increases in unemployment, and therefore unpaid bills, need for aid, etc.

Our spreadsheet model shows the economic challenges ahead. Suffice to say that, without a guarantee of rental housing costs, we are looking at a wave of both evictions and illnesses, and further downstream costs that they cause.