“Big Beautiful” Bill to Reduce Efficiency in Public Housing, Cost up to $1 Billion in Utilities Annually

. Posted in News - 0 Comments

United States House of Representatives 2025 H.R. 1, “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” as engrossed by the House on May 22, would cancel funding from the Inflation Reduction Act for the Green and Resilient Retrofit Program, a dual-purpose climate and efficiency program. This program will reduce public housing expenditures on utilities by between $600 million and $1 billion per year. If the bill were to pass into law as written, this program would be cut and these utility costs would continue to be borne by taxpayers.

![Congress.gov. H.R.1 – One Big Beautiful Bill Act. 119th Congress 2025 – 2026. Sponsor Representative Arrington, Jodey C [R-TX-19]. Introduced 05/20/2025. Engrossed in House 05/22/2025.](https://masslandlords.net/app/uploads/big-beautiful-bill-screenshot-of-version-passed-by-house.png)

A screenshot of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, H.R. 1, which will eliminate funding for efficiency in public housing utilities.

The purpose of this program, as stated by HUD program documentation published May 2024, now available for public inspection at MassLandlords.net, had six parts:

- “Substantially improve energy and water efficiency...;

- “Address ... synergies that can be achieved between efficiency, emissions reduction, and resilience investments;

- “Enhance indoor air quality and resident health;

- “Implement the use of zero-emission electricity generation and energy storage;

- “Minimize embodied carbon and incorporate low-emission building materials or

- processes; and

- “Support building electrification.”

The first bullet point was the main part of the program: reducing the cost of heat and hot water. Taxpayers presently pay more for public housing heat and hot water than private housing operators do.

MassLandlords sampled more than 20% of public housing authority budgets (by unit), including Atlanta, Boston, Chicopee, Chicago, New York, Seattle and Worcester, to get a sense of differences in climate and scale. We estimated that the U.S. spends roughly $3 billion per year on utilities for public housing units, or $250 per unit per month, compared with $162 per unit per month for the average U.S. household. This is an overage of roughly 35% relative to market. Explicit per-unit utility costs from the Worcester Housing Authority and Chicopee Housing Authority are lower, each around $200 per unit per month, implying inefficiency of only 20% relative to the market. This brackets the range. The total cost of the bill would therefore be between $600 million and $1 billion per year in avoidable utilities.

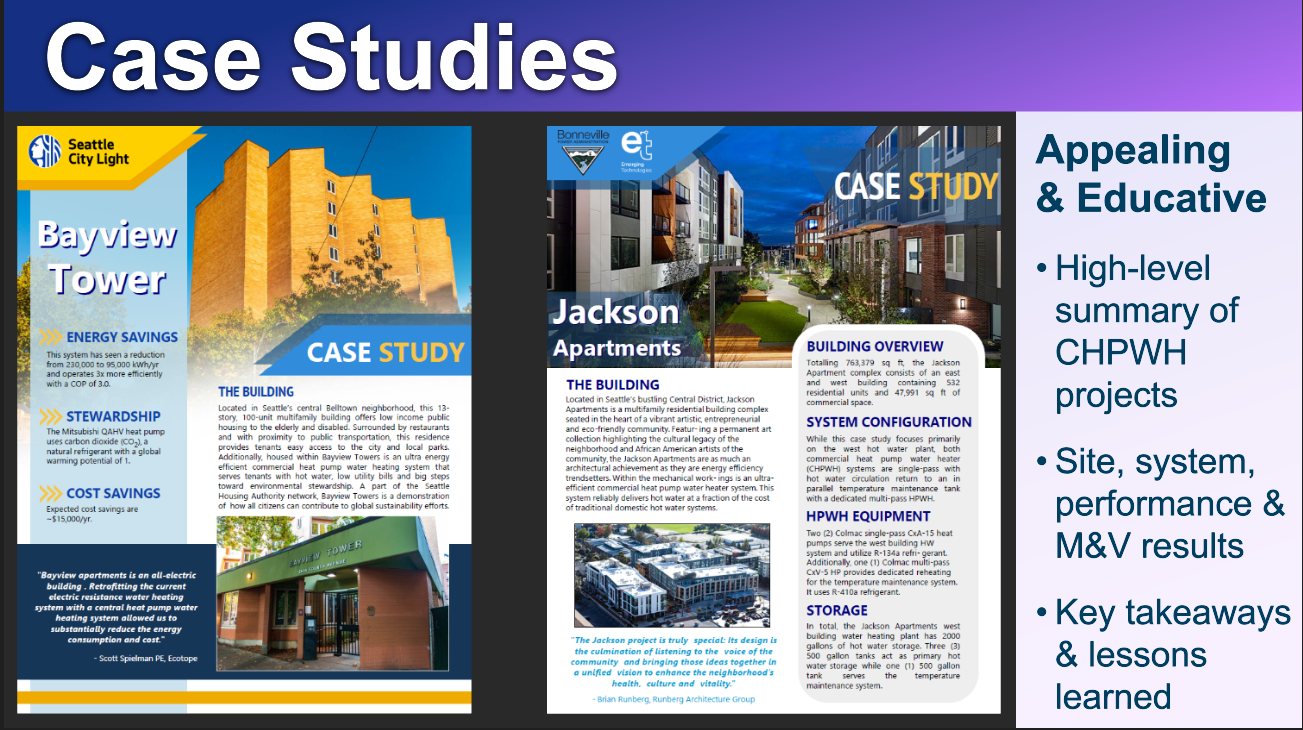

This slide from a presentation by the Advanced Water Heating Initiative, an industry consortium dedicated to heat pumps for water heating, shows how heat pumps reduced the Seattle Housing Authority’s energy consumption from 230,000 kWh/yr to 95,000 kWh/yr, a net savings of $15,000 per year for this one building for water heating alone. Water heating is usually a smaller energy consumption than space heating.

Public Housing, like Market Housing, Needs Regular Reinvestment

Public housing should have utility costs far below the average market rate U.S. household, since public housing units are almost entirely co-insulated in large blocky structures, as opposed to standalone single-family homes, which leak heat in all directions. The higher costs will be because of a few reasons.

One reason is that public housing renters likely consume more energy simply because they aren’t paying the full cost of it; utilities are heavily or fully subsidized in public housing. This is hard to fix. A second reason for high costs is relatively easy to fix: antiquated equipment is inefficient even when operating at peak performance. If it breaks down, spare parts are no longer readily available, and maintenance requires specialty knowledge.

Heat and hot water are the main costs. There are two types of housing authority systems. In the northeast, we often have decades-old, room-sized gas water heaters and boilers. Even though gas is cheap per therm, much of the heat we release in these old machines goes up the chimney as waste.

In the Pacific Northwest, we don’t have as much gas infrastructure. We often use electric resistance, cheaper to install but much more expensive to operate. Electricity has the potential to do any kind of work, from powering electronics to driving vehicles, across any distance. Generating heat from electric resistance is literally the least useful, most expensive thing to do with it. We normally get waste heat from electricity only after using it to do something else, like power a laptop that gets hot after many hours of use.

If we were considering what type of heat we’d want in our own homes, none of us would choose an ancient gas boiler or electric resistance baseboard. We would want to invest in newer technology if possible. This is why the Inflation Reduction Act allocated funding to replace these systems in public housing.

The Green and Resilient Retrofit Program mentioned climate change extensively. For this reason, it may be collateral damage in an ideological battle. The same technology used to address climate change, the heat pump, is also extremely efficient.

A cold-rated heat pump operating in a cold climate will be roughly cheaper than any gas boiler or furnace, all else being equal (insulated, air-sealed, properly sized, cold-rated). Any heat pump at all will be roughly 70% cheaper than electric resistance. Heat pumps use electricity to carry preexisting heat around. All properly installed heat pumps should pay for themselves over time. Even better, they produce no soot, carbon monoxide or other exhaust gases during normal operation. Heat pumps are win-win. As they become more widespread, up-front costs and maintenance costs decrease (see Wright’s law).

We should all want government to operate efficiently. We should demand it, because we pay for it. But as government has grown to the point where it touches all aspects of our lives from home to abroad and everything in between, it has grown too complex for omnibus bills.

It is impossible to reconcile the Big Beautiful Bill with the administration’s stated purpose to increase efficiency. At time of writing, the bill had not yet become law.