If You Own or Are Thinking About Buying Mass. Coastal Property, Learn About Flood Risk, AMOC and Other Factors

| . Posted in News - 0 Comments

By Eric Weld, MassLandlords, Inc.

Massachusetts coastal real estate can be a strong investment, but anyone considering buying property along our state’s 1,500 miles of coast has to factor in flood risk. Fast-rising sea levels are combining with intensifying storm surges and increasing ground water levels, multiplying the flood risk for coastal property, and must be manhere's aged as part of investments. Separate flood insurance is a must.

MassLandlords Executive Director Doug Quattrochi attended a screening of Inundation District, a film about how the Boston seaport already floods on a regular basis.

There are several factors contributing to sea level rise and coastal flood and erosion risk. This article is our admonition that Massachusetts is more vulnerable to sea level rise than any other place in the U.S., thanks largely to a phenomenon called the AMOC.

What is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation?

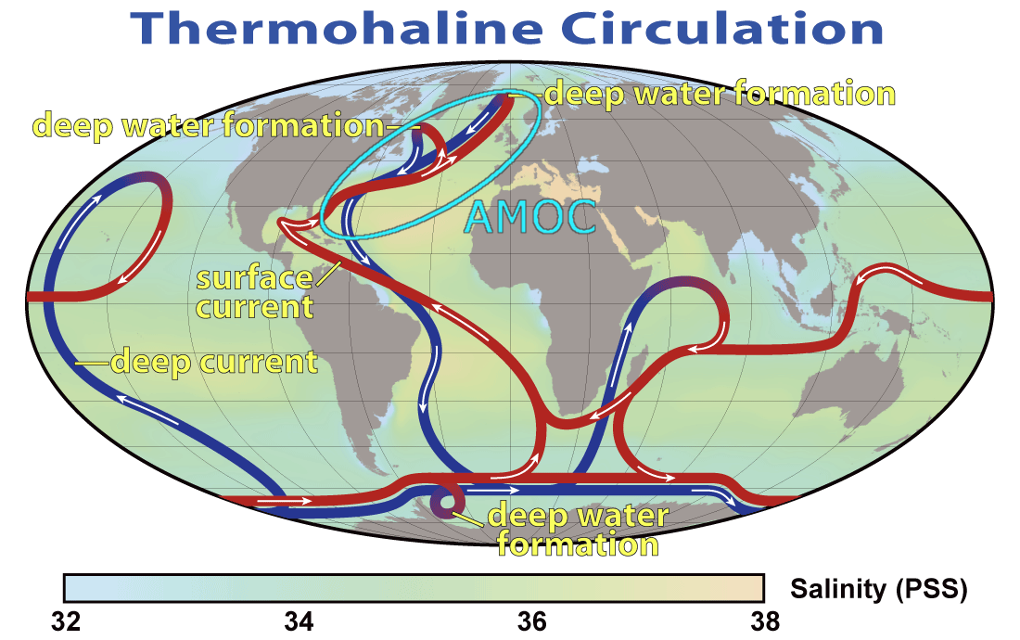

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a globally impactful phenomenon that runs south-north from Brazil, up past Florida and Massachusetts, then across the Atlantic Ocean to London, and back again, in constant motion. The Gulf Stream that flows about 100 miles off the Massachusetts coast is part of the AMOC. The 62-mile-wide Gulf Stream is a fast ocean current that starts in the Gulf of Mexico and transports warm water to the northern Atlantic, helping moderate climates along the way, such as in Massachusetts.

The Gulf Stream’s steady flow also modulates the sea level around Massachusetts and other parts of the eastern seaboard, positively lifting away a mass of ocean that would otherwise flow into and over the land that comprises our state. Without the AMOC and its Gulf Stream, the sea level around Massachusetts would be several feet higher.

Over geological time, the AMOC has slowed on occasion, and even stopped, or collapsed altogether. It’s been some 12,000 years since the last time that happened. But some recent research is suggesting that an AMOC collapse could happen within the next 30 years.

Coastal property owners and prospective investors should be aware of AMOC. You must factor in flood insurance and protections to coastal property purchases and profit estimations. Some investments may not automatically appreciate if precipitous sea level rise threatens the structure and surroundings.

A Closer Look at AMOC

It’s no longer news that sea levels are rising around the world, including in the Atlantic Ocean and along the Massachusetts coast, due to melting Greenland glaciers, caused by global warming. Greenland’s glaciers are melting at a rate of about 193 square kilometers per year, according to research by the journal “Nature.” That translates to about 400 billion tons of fresh water added to the North Atlantic every year. The rate of ice loss is accelerating faster than previously believed, and every glacier in Greenland has had some melting. (Antarctic glaciers are also melting, but so far not at the rate of Greenland’s ice masses. If Antarctic glaciers melted at the same rate as those in Greenland, global sea level rise would multiply several times.)

Even without a collapse of the AMOC, sea levels will continue to rise and flood risk for coastal property owners will continue to increase. An AMOC collapse ups the need to be aware of what you are investing in on the Massachusetts coast.

There’s another effect of all that fresh water from Greenland’s glacial melt flowing into the Atlantic Ocean and into the AMOC’s saltwater. The massive amounts of non-salt, cold water are affecting the AMOC’s circulation, evidence suggests, slowing it down and setting the stage for downstream shifts in Atlantic sea levels and impacts on the entire world’s climates.

It sounds a little like the plot of a Hollywood disaster blockbuster. But the implications of a shifting or slowing AMOC are vast, calamitous and not easily understood. So far, this looming potential disaster has not moved onto mainstream radar screens. But if some ocean scientists’ predictions come true, an AMOC shift will likely exacerbate and further accelerate rising ocean levels. It’s possible some parts of the Massachusetts coast could be submerged in outlying regions – low-lying promontories like Plum Island and others.

While possible, that’s an extreme forecast. There are many other ways that AMOC changes could have widespread impacts on the lives of everyone living near the Atlantic Ocean.

Varying Forecast Models

Opinions vary as to the timing and severity of outcomes of an AMOC collapse. Several studies conclude that the AMOC is slowing. But why it is slowing is a complex consideration. It could be primarily due to effects from globally warming temperatures caused by greenhouse gases caught in the earth’s atmosphere. There have been centuries-long rises and falls over geological time. Human-caused climate change layers on large amounts of uncertainty.

Predictions as to outcomes and/or a complete collapse of the AMOC also vary, from immediate to very distant, with many variables at play. Probabilities are also wide-ranging, and the research depth and credibility of each study must be weighed in.

A 2019 Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) raised awareness of the AMOC and its circulation concerns. The IPCC report, which has since been challenged by more recent studies, predicted that an AMOC collapse is very unlikely during this century. The report also concluded that it is very likely sea levels will continue to rise globally over the remainder of the 21st century, and that floods that used to occur every 100 years will become annual events for many areas.

However, a more recent analysis, a 2023 study from the University of Copenhagen, estimated with 95% certainty that this important Atlantic Ocean circulation could completely stop, or collapse, sometime between 2025 and 2095, with 2057 the most likely year, or tipping point, in their analysis.

That report was corroborated by an open letter signed by 44 prominent ocean and climate scientists and presented at the Arctic Circle Assembly held in Iceland in October 2024. The letter notes that the University of Copenhagen research rendered the IPCC’s outlook obsolete and “greatly underestimated.” The scientists urged immediate action in their letter, stating that a collapse of the AMOC could lead to “devastating and irreversible climate impacts” around the world.

A study published in August 2025 models AMOC collapse even under low-emissions scenarios (Shutdown of northern Atlantic overturning after 2100 following deep mixing collapse in CMIP6 projections, Drijfhout et al, Environmental Research Letters). It's hard to excerpt any single sentence from this paper; skim the paper for an overview of the complexity of climate modeling.

In considering these competing studies, the preeminence of and high respect among scientists globally for IPCC research and probability models should be factored in. Here’s what the IPCC says in its 2023 6th Synthesis Report:

“B.3.3. The probability of low-likelihood outcomes associated with potentially very large impacts increases with higher global warming levels (high confidence). Due to deep uncertainty linked to ice-sheet processes, global mean sea level rise above the likely range – approaching 2 m [meters] by 2100 and in excess of 15 m by 2300 under the very high GHG [Greenhouse gas] emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5) (low confidence) – cannot be excluded. There is medium confidence that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation will not collapse abruptly before 2100, but if it were to occur, it would very likely cause abrupt shifts in regional weather patterns, and large impacts on ecosystems and human activities. {3.1.3} (Box SPM.1)”

Yet a further study, by Nature in 2024, found that part of the AMOC in the North Atlantic has indeed been weakening for two decades, contributing to regional sea level rise.

Past occurrences of AMOC collapse buttress possibilities for its impending collapse now. The AMOC has collapsed many times throughout earth’s history – about once every 5,000 years, and most recently about 12,000 years ago during the last Ice Age, according to a March 2025 PBS Terra documentary.

The sum of the above analyses indicates that scientists, including IPCC researchers, agree that global warming increases the probability of catastrophic sea level rise, that the AMOC is displaying signs of shifting or weakening, and that a total collapse would have great impact on weather and life around the world. What the composite research does not agree on is highly confident projections of timing or severity of AMOC weakening. The timing inconsistency of the research in no way invalidates or dilutes climate science. Rather, the studies reflect science methodology: models are informed by data available at the time; when new data or understanding become available, models are updated accordingly.

What Would an AMOC Collapse Look Like?

Despite their lack of alignment on timing, scientists agree that northern Atlantic countries like Norway, Scotland and Iceland would take the brunt of climate impacts in the case of AMOC and Gulf Stream collapse. One prediction estimates a drop in average temperatures across Europe of 10-15 degrees Celsius. Another suggests an AMOC collapse could pose an existential threat to some countries’ populations. Other predictions are less dramatic but still concerning.

The U.S. east coast would also be greatly affected, Boston very much included. Rising sea levels would be one of the most acute and impactful changes. In the absence of warm water transported north via the Gulf Stream, winters would become more severe in the northern hemisphere, while hurricanes in the tropics, along with storms and precipitation would all intensify.

Global climates, agricultural patterns, animal habitats and ways of human life would all be dramatically affected by an AMOC collapse. Moreover, such a current collapse would exacerbate global warming further by overheating the Amazon rainforest region and triggering releases of carbon from trees in the south and faster glacial melting.

It’s impossible to say exactly where the Massachusetts coast would end up after an AMOC collapse. Some properties would surely be under water, literally and economically. And once the AMOC collapses, it could be a thousand years or more before it begins to circulate again.

Separate Flood Protection Needed

If this AMOC analysis sounds gloomy, it is. An AMOC collapse is more than zero percent possible.

We impart this information not to alarm (okay, maybe partly to alarm), but rather to provide a heads up and to strongly advise preparation and insurance protection against its possibility, no matter how remote you think such an event might be.

Even if you consider an AMOC collapse far-fetched, sea level rise and frequent flooding is already underway and well-documented. First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that publishes flood and climate data, found 336,200 Massachusetts properties to be at risk of substantial flooding in the next 30 years. First Street notes that Boston is home to the greatest number of flood risk properties with 19,200, or 19%. It also lists coastal and near-coastal communities like Hull, Dennis Port, Cambridge, Salem and Quincy seeing steep increases (Dennis Port, 299%) in the number of flood risk properties over the next three decades.

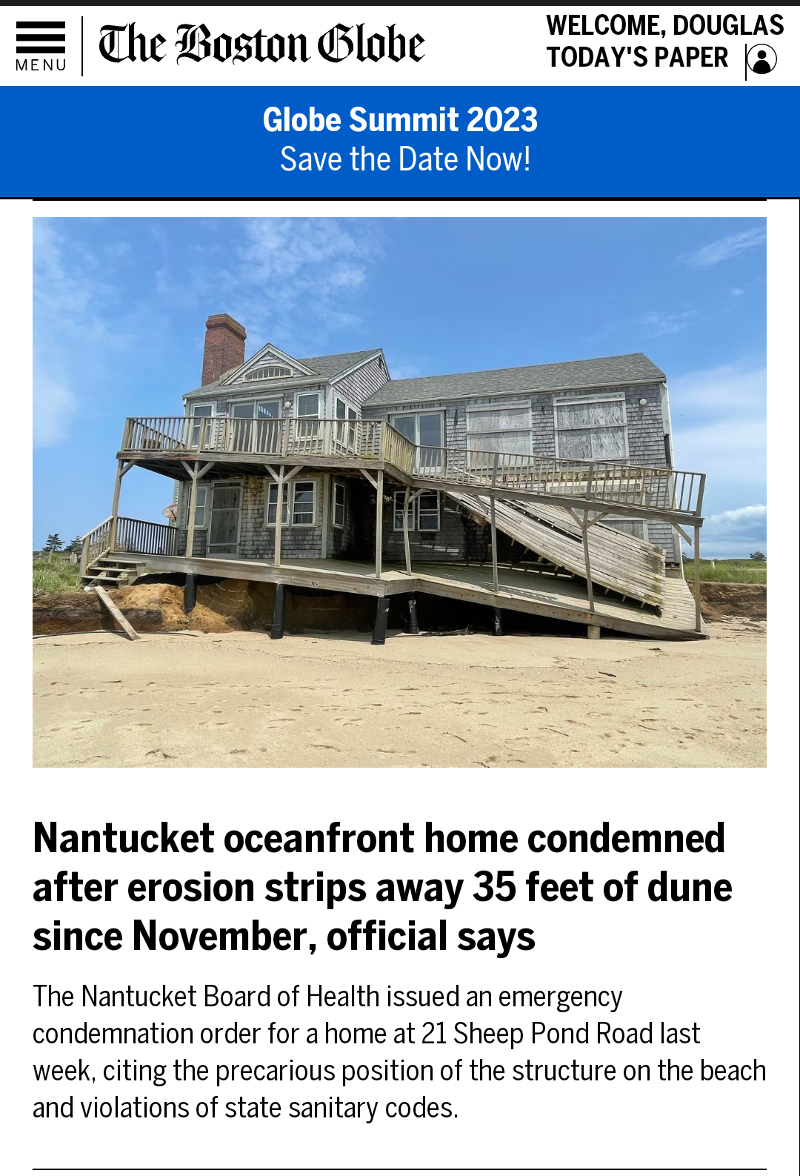

Scenes like this house on Nantucket, are being repeated all along the 1,500-mile Massachusetts coastline, with several houses being structurally endangered, condemned, moved and demolished after their foundations erode from under them. A multimillion Wellfleet mansion was torn down in February as it tottered near the edge of a fast-receding beach cliff. Editorial use, Boston Globe.

Coastal Erosion

Flooding is a major concern for coastal and near-coastal properties in Massachusetts, but it’s not the only threat posed by rising sea levels. As a few owners of expensive oceanside mansions have recently found out, eroding shorelines also directly threaten the viability of their homes’ foundations and structure.

The most documented example is a multimillion-dollar mansion that until very recently tottered on a beachside cliff in Wellfleet. Known as the “Blasch House,” the name of the couple who built the mansion atop a sand bluff in 2010, the property was purchased for $5.5 million by John Bonomi in 2022. With a bluff eroding at the rate of 3.8 to 5.6 feet per year, owners of the property had lobbied the town for permission to build a seawall to protect the property, but were denied due to impacts that would have on surrounding coastal areas. It was estimated by Bryan McCormack, a coastal processes specialist with Woods Hole Sea Grant and Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, that the house would tumble into Cape Cod Bay within three years.

The home was demolished in February 2025. It’s uncertain who funded the demolition, but one report confirms the town did not pay for it. Bonomi may never recover his investment.

Several other Cape Cod properties have had their foundations washed away from under them in recent years. Some have moved their homes inland to buy more time. Other properties have been condemned for safety reasons. Nantucket is another community dealing with fast-eroding beaches and facing steep damages from high-priced endangered properties.

It’s not only private properties or homes that sustain increasing impacts from flooding and erosion. The Boston Seaport, a monumental development project now in its second decade, flooded 19 days in 2024-25 due to high tides overrunning its sea level surface. Roads, walkways, bridges, power lines, commerce and public services are all impacted by increased flooding and erosion.

By some estimates, high tide flooding days could increase to nearly half the year by 2050 around Boston Harbor. Notably, those high tide flood days are caused by rising sea levels; storm surges and intensifying rainfall will add to the flood tallies. And then there’s the possibility of an AMOC collapse, which greatly multiplies flooding and erosion concerns.

Some of these coastal markets are starting to show the impacts of flood risk. Nantucket is seeing overall decline in average real estate prices, and specific properties on Cape Cod are diminishing in value.

The thermohaline circulation, or temperature-salinity current, is the global network of ocean currents that are driven by changes in temperature and salt levels between parts of the ocean. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) surface current (red) pulls feet of sea level away from the US eastern seaboard before sinking (blue).

How Much Flood Protection Do You Need?

Flood protection is not included in most property insurance policies, so separate coverage is required for flooding. Be sure to purchase flood insurance coverage both for your building and for your personal property if First Street Foundation suggests a flood risk you cannot self-insure.

If you have leased tenants, you should also advise them to purchase separate flood insurance covering their personal belongings. Renters insurance will protect belongings against fire, theft and internal water damage (like burst pipes), but not against floods.

The place to start is the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which is operated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). NFIP may be more affordable than coverage through private companies.

However, NFIP insurance will only cover buildings up to $250,000 and private contents up to $100,000. Of course, many Massachusetts coastal properties have value well over that amount, so you will most likely want to purchase additional private insurance for replacement or loss-of-use.

Other measures, like raising a house up several feet, can be cost-effective and extend the life of the property without changing its location. Or, just raising the level of house systems like HVAC, plumbing and electric meters to protect from flooding can be done for nominal cost. Flood mitigation measures on individual properties will likely lower the price tag on flood insurance premiums.

Seawalls and natural solutions like planting vegetation along shorelines can also help save built structures in shoreline communities, though at high expense, and with potential environmental impacts. Seawalls, for example, are no cure; they only deflect ocean waves, which can then pile up in neighboring properties, accelerating erosion in a race to the bottom of the sea.

Flood insurance premiums might cause some sticker shock, depending on your property value, flood mitigation and flood risk as determined by NFIP or a private insurance company. It could run several hundred dollars or well over that per month for high-value properties.

But, considering an AMOC collapse and the host of other flood forces crowding the Massachusetts coast, full replacement coverage could be the best investment you make as an owner of increasingly endangered coastal property.